|

.

"I don't like war, it spoils the soldiers,

dirts their uniforms ..."

Grand Duke Constantine

|

Uniforms of Russian Infantry.

"A soldier has no time for smartness on campaign."

- Kutusov in 1812

Many Russian generals in that time were excessively concerned with details of dress,

which in the case of some officers became an obsession. Their soldiers were busy for

hours polishing the leather pouch and carbine belt, boots, buttons, and headgears.

Tsar Alexandr had more relaxed attitude on uniforms than his father, although still

not being as practical as was Suvorov or Kutuzov who were rather exceptions in this aspect.

While seeing the soldiers during campaign polishing their white leather belts, Kutuzov stopped

and said: "I don’t want any of that. I want to see whether you’re in good health,

my children. A soldier has no time for smartness during a campaign.”

Once a year each infantryman received 2 pairs of boots, 3 pairs of stockings, 1 headwear,

1 knapsack, 1 coat, 1 pair of trousers. Once every two years he received 1 greatcoat.

The Russian cloth factories were obliged to sell part of their production in a fixed

price for the army. In general the production was insufficient and additional uniforms

were purchased from Britain, the major supplier of clothes and arms to Russia.

The style and design of Russian uniform changed several times, being influenced by the

Prussians and the French. The Prussians covered themselves with glory during the Seven Years War and Tsar Paul

(1754-1801) took them as example on which he dressed his troops disregarding the Russian

national tradition and different climate. For example coats were tighter and soldiers

had to wear the very unpopular in Russia gaiters. They also wore Prussian caps,

adopted the Prussian motto of “Gott Mit Uns” (God With Us) and had to powder and plait

their hair.

The greatness of Frederick the Great faded away in the military glory of Napoleon Bonaparte

and during the reign of Pavel’s son, Tsar Alexandr, the Prussian military fashion was

replaced by the French. But when Russia’s political and military position in Europe

was greatly strengthened after defeating Napoleon, the Russian uniforms became the model

for several western armies. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery then the Russians

must have been most flattered when in 1815 the Prussian army adopted to big degree the style and design of

Russian uniforms.

The average and minimal temperatures in Russian regions differ. In the European regions of Russia the average winter temperature sometimes falls below -15 °C; however,

sometimes it is much colder: even down to -30 °C for a month or two. One of the factors for these temperatures is Russia's geography: it is as northerly as Canada. (Brr).

Winter is a common excuse for military failures of invaders in Russia (General Winter and

General Snow. Failure in spring or fall is excused by General Mud :-)

Surprise surprise, such weather required warmer clothes for the troops !

The Russian infantrymen of Napoleonic Wars wore voluminous greatcoat (called shineli) made of rough cloth.

The army had to wear the greatcoats for seven months, from October 1st to May 1st.

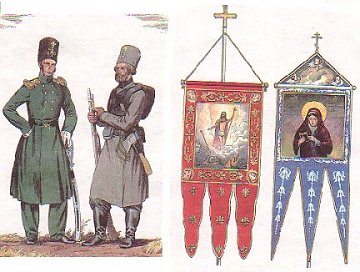

Left: Russian grenadier in 1802-1805 wearing the old-fashioned mitre cap and greatcoat.

Picture by Viskovatov, Russia.

Left: Russian grenadier in 1802-1805 wearing the old-fashioned mitre cap and greatcoat.

Picture by Viskovatov, Russia.

Right: Russian infantrymen and grenadiers in 1804-1807, wearing shakos and greatcoats.

Picture by Patrice Courcelle, France.

The greatcoat was a very popular wear although restricted faster movements on battlefield.

Officer Shimanski wrote: "Running in a greatcoat, I was fatigued..." (Russian greatcoats were longer than

those worn by the French and German troops).

The greatcoat was either brown-grey, grey, brown, dark green or black. In 1811 the greatcoat cuffs became colored,

which do not appear to have been universal. In the beginning of 1814 campaign was ordered to

wear on the greatcoat a white cloth strip to be tied around the left arm as a "field sign" to

distinguish Allied troops.

For parade the greatcoat and haversack were removed.

In 1808 the round knapsacks used by lower ranks since 1802 were exchanged for rectangular ones and made of black leather.

In the beginning of Napoleonic Wars the Russian infantry usually

removed the knapsack before combat. It happened in Austerlitz and in December 1806

at Garnovo. At Garnowo the infantry (in the wood) to make the good reception of the French

threw off their knapsacks. A vicious hand to hand combat in the wood followed.

Davout's infantry pushed the Russians back and they were unable to recover their 4,000

knapsacks. Later on however this custom was almost abandoned.

Between 1810 and 1815 there were only few cases where the backpacks were actually taken off

before combat. And even then it was done by one or two battalions rather than entire brigades.

The backapacks were not left on the ground but were taken to the rear by other battalions.

In a very cold weather they additionally wrapped a cloth made of linen or wool around their

feet, inside of the boots. This cloth was called onuchi (pronounced as onoochee) and had to be washed quite often as the feet easily sweated.

In 1809 was ordered:

In 1809 was ordered:

"the greatcoat is to be rolled 6.5 inches wide and worn over the left shoulder so that the soldier can freely hold the

musket behind it.

the lower ends of the greatcoat are to be tied

with a strap and buckle 3.4 inches from the end.

greatcoat and knapsack leather straps are not to be whitened.

the left knapsack strap is to be worn over the left shoulder on top of the greatcoat.

Picture: NCO of Orel Infantry Regiment in 1812-13, by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

The leather crossbelts were made of deerskin. They were white for musketiers and grenadiers

and black for jägers (light infantry). Several jäger regiments which were transferred from musketiers 2

years earlier, still retained their white crossbelts. The crossbelts supposedly have

being cleaned and whitened by the soldiers, but that was not rigorously obeyed during

campaign.

He wears grey, comfortable trouers, and his shako is protected with an oil-cloth.

In 1802 was ordered that the green coat (not the grey greatcoat) would be "double-breasted, of dark-green cloth, with

a standing collar of a special color for each Inspectorate; with cuffs the same color as the collar; with dark-green flaps

on the cuffs; with red kersey lining, with brass buttons and two shoulder straps, of a special color for each regiment in

an Inspectorate... In November 1807 was issued an order for all grenadier regiments:

"collars and cuffs of coats, as well as collars of greatcoats, are directed to be of

red cloth".

In 1814 a single breasted coat was introduced.

In April 1812 the musketier regiments were assigned shoulder straps according to seniority

within divisions. In 1810 all grenadiers were ordered to wear red shoulder straps.

In 1814 the grenadier and the newly formed grenadier-jäger regiments were ordered to adopt

yellow shoulder straps with initials in red, instead of the red shoulder straps with yellow

initials. Regiments who wore yellow shoulder straps were ordered to change into blue ones

and those with light blue change to green piped red.

All these changes were not actually adopted before the end of Napoleonic wars.

Picture: headwears of infantry in 1802-05, by Oleg Parkhaiev

Picture: headwears of infantry in 1802-05, by Oleg Parkhaiev

1 - grenadier mitre-cap (1802) of Life Grenadiers

2 - grenadier mitre-cap (1802) of Pavlovsk Grenadiers

3 - fusilier mitre-cap (pattern 1802) of Astrakhan Grenadiers

4 - grenadier shako (pattern 1805)

5 - jager shako (pattern 1803)

6 - grenadier officer shako (unofficial)

7 - kaski (pattern 1802) of Lifeguard Preobrazhensk

In the beginning of Napoleonic wars the tall and strong grenadiers wore mitre caps.

In 1802 they were almost the same form and size as under Tzar Paul. In February 1805 in grenadier regiments the mitre caps were replaced with new ones.

In 1803 (two years before Austerlitz Campaign) all lower ranks in musketeer regiments who were authorized hats were given shakos.

Below is a picture of uniforms worn by the Russian infantry in Austerlitz Campaign in 1805.

Picture: Russian infantry in Austerlitz Campaign in 1805.

Picture by Andre Jouineau, France.

Upper row: NCO, musketier, grenadier, grenadier with rolled greatcoat, drummer

Lower row: infantryman in greatcoat, officer in parade uniform, officer in campaign uniform.

In 1809 there were several changes introduced in the grenadier regiments.

The shako cords (etishkety) were introduced:

- - - white for privates

- - - white with a mixture of black and orange for NCOs and musicians

(In 1811 white cords with only their tassels having black and orange mixed in.)

Colors were assigned for shako pompons:

- - - white around green center for I Battalion

- - - green around white center in the II Battalion

- - - red around yellow center in the III Battalion

Company-grade officers of grenadier regiments were ordered to wear a shako instead of

the hat when in formation, with silver cords with a mixture of black and orange,

only the tassel and ring being wholly silver. The powdering of the hair

was discontinued for officers in grenadier regiments.

In 1810 in the jager regiments, the carabiniers and strelki were given short swords

patterned after the swords in the rest of the infantry.

In 1811 these carabiniers and strelki were ordered to have tall black plumes on

their shakos of the same pattern as those confirmed at this time for grenadier regiments:

black for privates; black with a white top with an orange stripe down its middle for NCOs; and red for drummers and fifers.

(Within few day however the plumes were abolished for the strelki.)

The grenadiers and strelki of jager regiments were also ordered 3-flamed grenades

on their shakos.

In 1811 all grenadiers, carabiniers, strelki, fusiliers, and officers had their former thick

black plumes replaced with new and narrow ones.

In 1811 all grenadiers, carabiniers, strelki, fusiliers, and officers had their former thick

black plumes replaced with new and narrow ones.

New shako called kiver was introduced in 1812. See picture -->

It was received only by some units, other regiments wore the old ones, even as late as 1814.

The shako of the grenadiers and musketiers had brass chinscales.

The jägers however had their shako held on the head with

the help of one leather chin belt. There were white cords (peltizi) attached to the

shako. The cords for officers were silver. If during campaign the cords were not lost they

often were looped around the pompon.

During long march the shako was protected with a

special cloth cover and the cords were removed.

If shako was covered the plume could be removed and kept atop of the knapsack.

The shako cover was made of thick cloth saturated with wax.

The cover was most often black. In some cases on the cover was a

company number in yellow, although it was unofficially.

During long marches and in the camp the soldiers wore more comfortable forage round cap.

In summer the soldier no longer wore black, tall boots.

In summer the soldier no longer wore black, tall boots.

Instead they wore the elegant white one piece trousers-gaiters. See picture -->

For winter these would be replaced with white (dark green for jagers) one piece trousers-gaiters with black leather

"false booting."

During campaign, and in many battles, the infantrymen wore trousers. These were made of canvas or linen and could be grey, brown, green. The trousers were

comfortable and liked by the men, they were worn despite the repeated orders from regimental

officers.

A yellow brass badge was fixed to the cartridge box. It differed in shape between

various branches:

- - - in the guards heavy infantry the plate had a St.-Andrew's star

- - - for grenadiers it was in the form of a grenade with three flames.

- - - for musketiers in the form of a grenade with one flame.

- - - for the jägers it had a regimental number.

Officers' uniforms resembled those of the rank-and-file, though their coats had longer tails.

The junior officers were distinguished with epaulettes. The senior officers'

(majors, lieutenant colonels, and colonels) epaulettes had a fringe hanging from the edge.

Officer wore a gorget at his neck bearing a black and gold double eagle.

The gorgets were silver for 2nd lieutenants, silver with gilt edge for lieutenants, silver

with gilt edge and eagle for 2nd captains, gilt with silver eagle for captains.

The officers also wore the sash wrapped twice around the waist and knotted on the left side.

The sash was of silver fabric, with 3 interwoven horizontal lines of black and orange.

During campaign the officers wore green frock coats, grey breeches or grey trousers with red

stripes, and bicorn hat or shako. They also carried the black knapsack but the gorget and

sash were omitted.

NCO's pompon was quartered in red and white and his collar's upper edge was pipped white.

The drummers and fifers wore infantry coats with the addition of 6 white shevrons on each

sleeve, 6 white lace loops on the breast, and 3 on each cuff flap.

The grenadiers' drummers wore red instead of black plume.

Drums were copper with white cords, and hoops painted in white and dark green triangles. The drum apron was usually of light brown hide.

Uniforms of Russian infantry in 1812 Campaign, picture by Andre Jouineau, France.

Uniforms of the

Russian Army, 1801-1815

Pictures by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia

1812

| Infantry Division |

Regiment |

Shoulder

Straps |

Leather

Crossbelts |

| Guard |

Preobrazhensk Lifeguard

Semenovsk Lifeguard

Izmailovsk Lifeguard

Lithuania Lifeguard

Finnish Lifeguard

Jagers Lifeguard |

|

|

| 1st (Grenadiers) |

Life Grenadiers

Pavlovsk Grenadiers

St. Petersbourg Grenadiers

Yekaterinoslav Grenadiers

Count Arakcheiev Grenadiers

Taurida Grenadiers |

|

|

| 2nd (Grenadiers) |

Kiev Grenadiers

Moscow Grenadiers

Fanagoria Grenadiers

Astrakhan Grenadiers

Little Russia Grenadiers

Siberia Grenadiers |

|

|

| 3rd |

Chernihov

Mouromsk

Revel

Koporsk

20th Jägers

21st Jägers |

|

|

| 4th |

Tobolsk

Volhynie

Kremenchoug

Minsk

4th Jagers

34th Jagers |

|

|

| 5th |

Perm

Sievsk

Mohilev

Kalouga

23rd Jagers

24th Jagers |

|

|

6th

(quartered in

Finland) |

Azov

Uglitz

Nisov

Briansk

3rd Jagers

35th Jagers |

|

|

| 7th |

Pskov

Moscow

Libava

Sofia

11th Jägers

36th Jägers |

|

|

| 8th |

Archangelsk

Schlusselbourg

Old Ingermanland

Ukraine

7th Jagers

37th Jagers |

|

|

| 9th |

Nashebourg

Apsheron

Riazhsk

Yakoutzk

10th Jagers

38th Jagers |

|

|

| 10th |

Yaroslav

Kursk

Crimea

Bialystok

8th Jagers

39th Jagers |

|

|

| 11th |

Kexholm

Yeletz

Polotzk

Pernau

1st Jagers

33rd Jagers |

|

|

| 12th |

Smolensk

Narva

Alexopol

New Ingermanland

6th Jägers

41st Jägers |

|

|

| 13th |

Vielikie Louki

Saratov

Galich

Penza

12th Jägers

22nd Jägers |

|

|

| 14th |

Tula

Tenguinsk

Navazhinsk

Estonia

25th Jagers

26th Jagers |

|

|

| 15th |

Vitebsk

Kozlov

Kolyvan

Kura

13th Jagers

14th Jagers |

|

|

| 16th |

Nyslott

Ohotzk

Kamchatka

Mingrelia

27th Jagers

43rd Jagers |

|

|

| 17th |

Riazan

Briest

Bielosersk

Willmanstrand

30th Jägers

48th Jägers |

|

|

| 18th |

Vladimir

Tambowsk

Dnieper

Kostroma

28th Jagers

32nd Jagers |

|

|

19th

(stationed in

Georgia and

Caucasus) |

Kazan

Suzdal

Belev

Sevastopol

17th Jagers

..th Jagers |

|

|

20th

(stationed in

Georgia and

Caucasus) |

Troitsk

Tiflis

Kabardia

...

9th Jagers

15th Jagers |

|

|

21st

(quartered in

Finland) |

Neva

Petrovsk

Lithuania

Podolia

2nd Jagers

44th Jagers |

|

|

| 22nd |

Vyborg

Viatka

Staryi Oskol

Olonetz

29th Jagers

45th Jagers |

|

|

| 23rd |

Rilsk

Yekaterinbourg

Selenguinsk

-

18th Jagers

???? |

-

|

-

|

| 24th |

Hirvan

Boutyrsk

Ufa

Tomsk

19th Jägers

40th Jägers |

|

|

25th

(quartered in

Finland) |

1st Marines

2nd Marines

3rd Marines

Voronezh

31st Jägers

47th Jägers |

-

-

-

|

-

-

-

|

| 26th |

Nizhegorod

Ladoga

Poltava

Orel

5th Jägers

42nd Jägers |

|

|

| 27th |

Odessa

Vilno

Tarnopol

Simbirsk

49th Jägers

50th Jägers |

|

|

| 28th |

garrison units

in Siberian and Orenburg

territories

|

| 29th |

garrison units

in Siberian and Orenburg

territories

|

30th, 31st,

32nd, 33rd,

34th, 35th,

36th, 37th,

38th, 39th,

40th, 42st,

42nd, 43rd,

44th, 45th,

46th, 47th |

In March 1812 was ordered to form

18 new infantry divisions (30th-47th)

from the 2nd 'replacement' battalions

(without their grenadier companies)

and 4th 'reserve' battalions.

(The 2nd 'replacement' battalions

were not detached from 19th-20th Div.

stationed in Georgia and the Caucasus.

Their 'reserve' battalions were disbanded.)

|

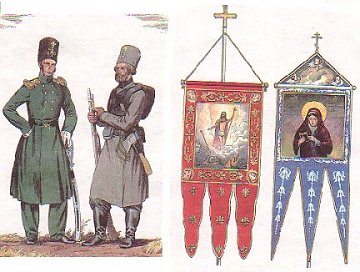

Picture: opolchenie in 1812, by Oleg Parkhaiev.

Picture: opolchenie in 1812, by Oleg Parkhaiev.

The opolchenie (militia) was raised in autumn of 1806. It was raised again in 1812.

Serfs formed the bulk of the opolchenie, they were chosen by ballot from every 4-5 men

per 100 aged 17 to 45 and required the permission of their landlord.

The middle classes; clerics, professionals and intelligentsia joined the opolchenie

voluntarily.

The NCOs came from training battalions and retired soldiers. The officers came from noblemen

and those who had served in the Army before. The nobility elected the generals and officers

of the opolchenie.

Some sources state the opolchenie numbered not less than 420,000 men, a more

realistic figure would be just over 200,000 men. The opolchenie took an active part

in the military actions at Borodino, Polotsk, Viazima, Krasnoi and

Charniki, and many other battles. These cohorts were used as a source of replacements to fill

out the depleted line units late in the war as well as employed as independent combat units.

At Maloyaroslavets, pike armed Opolkenie were used to fill in the 3rd rank of the units that

had been mauled at Borodino. There are repeated references to the St. Petersburg

Opolchenie being absorbed into line units during the period around the second battle

of Polotsk. They were not confined to direct military uses but also allowed the release

of regulars from logistic tasks. These included maintaining garrisons, trains, parks, camps, stores, and worked as nurses, miners,

policing, guarding prisoners and so forth. (Source: "The Opolchenie" by Dr S. Summerfield)

|

Picture: Russian infantry in 1812.

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

Picture: Russian infantry in 1812.

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

The Russians had a bad reputation for drinking. The troopers received 3/8 litre of

‘liquor’ but prefered kvas, a native beer. Anything stronger than beer was often

diluted with water. Each private, combatant and noncombatant carried a wooden “bottle” protected

by leather.

The Russians had a bad reputation for drinking. The troopers received 3/8 litre of

‘liquor’ but prefered kvas, a native beer. Anything stronger than beer was often

diluted with water. Each private, combatant and noncombatant carried a wooden “bottle” protected

by leather.

Picture: Russians (left) versus Austrians (right), France's allies in 1812.

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

Picture: Russians (left) versus Austrians (right), France's allies in 1812.

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev, Russia.

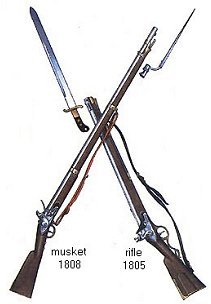

In the beginning of Napoleonic Wars the inferior quality of powder and muskets plagued

Russian infantry. Another problem was the outdated metallurgical and gunpowder industries.

In the beginning of Napoleonic Wars the inferior quality of powder and muskets plagued

Russian infantry. Another problem was the outdated metallurgical and gunpowder industries.

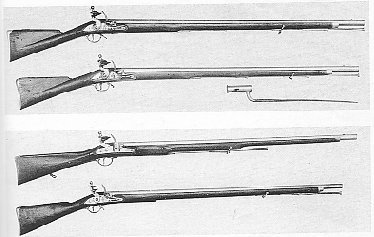

Picture: British infantry muskets.

Source: Brent Nosworthy - "With Musket,

Cannon, and Sword."

Picture: British infantry muskets.

Source: Brent Nosworthy - "With Musket,

Cannon, and Sword."

Left: Russian grenadier in 1802-1805 wearing the old-fashioned mitre cap and greatcoat.

Picture by Viskovatov, Russia.

Left: Russian grenadier in 1802-1805 wearing the old-fashioned mitre cap and greatcoat.

Picture by Viskovatov, Russia.

In 1809 was ordered:

In 1809 was ordered: Picture: headwears of infantry in 1802-05, by Oleg Parkhaiev

Picture: headwears of infantry in 1802-05, by Oleg Parkhaiev

In 1811 all grenadiers, carabiniers, strelki, fusiliers, and officers had their former thick

black plumes replaced with new and narrow ones.

In 1811 all grenadiers, carabiniers, strelki, fusiliers, and officers had their former thick

black plumes replaced with new and narrow ones.

In summer the soldier no longer wore black, tall boots.

In summer the soldier no longer wore black, tall boots.

Picture: opolchenie in 1812, by Oleg Parkhaiev.

Picture: opolchenie in 1812, by Oleg Parkhaiev.

Unfortunately Russia was the land of useless formalities.

The taste for parades was carried beyond all bounds. Parade ground precision was what

was instilled into recruits and musketry training was neglected.

Unfortunately Russia was the land of useless formalities.

The taste for parades was carried beyond all bounds. Parade ground precision was what

was instilled into recruits and musketry training was neglected.

In the summer of 1811 were conducted divisional maneuvers. In such maneuvers

participated infantry, cavalry and artillery. Special attention was paid to the

cooperation of the three arms and to skirmishing but multi-divisional maneuvers were rare.

During the army maneuvers in May 1812 the 3rd Infantry Division under General Konovnitzin (see picture)

was held up as a model for the army. In the battle of

In the summer of 1811 were conducted divisional maneuvers. In such maneuvers

participated infantry, cavalry and artillery. Special attention was paid to the

cooperation of the three arms and to skirmishing but multi-divisional maneuvers were rare.

During the army maneuvers in May 1812 the 3rd Infantry Division under General Konovnitzin (see picture)

was held up as a model for the army. In the battle of

Kutuzov (see picture) insisted that troops must be inspected and tested in aimed fire.

Barclay de Tolly writes: "The purpose of the training is not in that the men would pull

the triggers evenly and all at the same time, but that they would aim well..."

He also issued several orders on the training in aimed fire.

Kutuzov (see picture) insisted that troops must be inspected and tested in aimed fire.

Barclay de Tolly writes: "The purpose of the training is not in that the men would pull

the triggers evenly and all at the same time, but that they would aim well..."

He also issued several orders on the training in aimed fire.

The line formation had been standard during the XVIII Century but lost popularity after the French triumphs with columns during the Revolutionary Wars.

Column was the favorite formation for the Russians. Any movement in line was inconvenient, while columns moved faster and easier maneuvered.

The line formation had been standard during the XVIII Century but lost popularity after the French triumphs with columns during the Revolutionary Wars.

Column was the favorite formation for the Russians. Any movement in line was inconvenient, while columns moved faster and easier maneuvered.

The deeper the column was the heavier casualties it suffered from artillery fire.

Not only a direct hit could kill many soldiers,

a cannonball rolling and ricocheting was

breaking men's legs.

The deeper the column was the heavier casualties it suffered from artillery fire.

Not only a direct hit could kill many soldiers,

a cannonball rolling and ricocheting was

breaking men's legs.

In the battle of Borodino, Kutuzov ordered the 3rd 'Grenadier' Corps be placed so

the French would not be able to see it. Later that day General Leontii Bennigsen (see picture) visited

this corps and ordered to move it forward without informing the commander in chief.

In the battle of Borodino, Kutuzov ordered the 3rd 'Grenadier' Corps be placed so

the French would not be able to see it. Later that day General Leontii Bennigsen (see picture) visited

this corps and ordered to move it forward without informing the commander in chief.

"The situation of the Russians on Klux's right, in the open fields ...

was much worse. Lacking any cover at all, they suffered very heavy losses from artillery

fire. Shahovskoi ... reported to Prinz Eugen that his men were being destroyed.

The prince rode slowly along the line. At each battalion, his question 'How many men

have you lost ?' would be answered with a silent gesture to the lines of dead lying where they had fallen. ...

[Prinz Eugen] did nothing to alleviate the situation ... That the prince ... lacked sufficient initiative to move his divisions out of the French line of fire, or at least have them lay down,

beggars belief. It was Borodino all over again (where Prinz Eugen had commanded the 4th

Infantry Division); the Russian commanders had learned nothing and continued to squander their

men to absolutely no avail." (Digby-Smith - "1813: Leipzig" p 86)

"The situation of the Russians on Klux's right, in the open fields ...

was much worse. Lacking any cover at all, they suffered very heavy losses from artillery

fire. Shahovskoi ... reported to Prinz Eugen that his men were being destroyed.

The prince rode slowly along the line. At each battalion, his question 'How many men

have you lost ?' would be answered with a silent gesture to the lines of dead lying where they had fallen. ...

[Prinz Eugen] did nothing to alleviate the situation ... That the prince ... lacked sufficient initiative to move his divisions out of the French line of fire, or at least have them lay down,

beggars belief. It was Borodino all over again (where Prinz Eugen had commanded the 4th

Infantry Division); the Russian commanders had learned nothing and continued to squander their

men to absolutely no avail." (Digby-Smith - "1813: Leipzig" p 86)

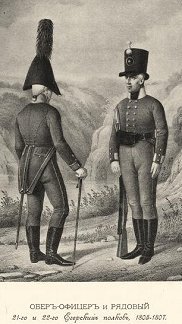

Pictures: officer and private

of 21st and 22nd Jagers in 1805-1807 (left) and

NCO of jagers in 1812-1816 (right).

Picture by Viskovatov.

Pictures: officer and private

of 21st and 22nd Jagers in 1805-1807 (left) and

NCO of jagers in 1812-1816 (right).

Picture by Viskovatov.

Generally the best were the Guard regiments, followed by grenadier, jager and musketier

regiments. We have selected eight regiments (3 grenadiers, 3 infantry, 2 jagers) which

- in our opinion - are the best. They have distinguished themselves on battlefield, captured enemy's color

and guns, or put up a gallant fight to beat off the enemy.

Generally the best were the Guard regiments, followed by grenadier, jager and musketier

regiments. We have selected eight regiments (3 grenadiers, 3 infantry, 2 jagers) which

- in our opinion - are the best. They have distinguished themselves on battlefield, captured enemy's color

and guns, or put up a gallant fight to beat off the enemy.

At Kliastitzi (see picture) the depot battalion of this regiment, while under hail of fire,

passed through a flaming bridge at full speed and took by storm all the building

defended by the

At Kliastitzi (see picture) the depot battalion of this regiment, while under hail of fire,

passed through a flaming bridge at full speed and took by storm all the building

defended by the