|

.

"... the English army was absurdly under-rated in foreign countries

and absolutely despised in its own ...the ill-success of the expeditions

in 1794 and 1799 appeared to justify the general prejudice. "

England, both at home and abroad, was in 1808

scorned as a military power ..."

Napier - “History of the

War in Peninsula 1807-1814” p 21

|

The British Army

Strength, Deployment, Training and Quality.

The British army came into being with the merger of the Scottish Army and the English Army,

following the unification of the two countries' parliaments and the creation of the United Kingdom

of Great Britain in 1707. Under Oliver Cromwell, the army had been active in the re-conquest,

settlement and suppressing revolts in Ireland.

The army and navy, in building the Empire, fought Netherlands, Spain, France, and United States for supremacy in

North America, Africa and West Indies. It also battled many native tribes.

The British army came into being with the merger of the Scottish Army and the English Army,

following the unification of the two countries' parliaments and the creation of the United Kingdom

of Great Britain in 1707. Under Oliver Cromwell, the army had been active in the re-conquest,

settlement and suppressing revolts in Ireland.

The army and navy, in building the Empire, fought Netherlands, Spain, France, and United States for supremacy in

North America, Africa and West Indies. It also battled many native tribes.

During the Napoleonic Wars Great Britain had a powerful navy but

relatively small army. One of the barriers to recruitment was the army's fearsome reputation for loss

of life. For example the failing campaigns in Caribbean in 1790s caused thousands of

redcoats to perish through disease. Britain distrusted and disliked the armed forces,

considering them to be the weapons in the hand of the King.

Before Wellington the British army was not regarded as equal to some continental armies.

In England the idea of British army fighting alongside the Russians in 1807 was ridiculed.

The structure of the British Army was complex, due to the different origins of its various constituent parts.

The king was the nominal commander of the British army.

There was no chief of staff system in the British army at the time. At Waterloo there were approx. 150 British and KGL officers

listed as being part of Wellington's staff, and 33 of them were actually present at the battle.

Wellington had been highly critical of the competence and lack of experience of many

of his staff. Various departments were commanded by officers.

Wellington could not have worked with a chief of staff who was also his second in command.

The Duke made his own decisions and rarely shared his plans.

Sir Oman put it: "He [Wellington] did not wish to have a Gneisenau or Moltke at his side:

he only wanted zealous and competent chief clerks.' He himself was de facto head of each staff department.

Prussian General Gneiseanu and French Marshal Soult could, and would, assume an independent

command of their armies if necessary. (Mark Adkin - "Waterloo Companion")

King George III

George III attacked George and tried

to "smash his head against the wall"

and "foam was coming from the king's mouth".

King's eyes "were so bloodshot they looked

like currant jelly."

The king was the nominal commander of the British army.

The coming of George III to the throne brought the first British born king for 50 years.

His predecessor, King George I, was a German who did not speak a word of English,

but was Protestant. So he started the rule of the House of Hanover, under whom Britain

achieved wealth.

The king was the nominal commander of the British army.

The coming of George III to the throne brought the first British born king for 50 years.

His predecessor, King George I, was a German who did not speak a word of English,

but was Protestant. So he started the rule of the House of Hanover, under whom Britain

achieved wealth.

George III, by the Grace of God the King of Britain, suffered from deteriorating mental health.

He is also known for the Brits as "The King Who

Lost America" and for the Americans as "The Man Who Fought Against Freedom and Democracy."

(In 1994 was filmed "The Madness of the King George". Some of the actors were nominated to

Oscars.)

The dumb George was having trouble with his eldest son, also George. In 1788,

George III attacked George and tried to "smash his head against the wall" and "foam

was coming from the king's mouth". King's eyes "were so bloodshot they looked like

currant jelly."

By the way, the next king was also George, but with the number IV.

He kept going "on laudanum and prodigious quantities of cherry brandy."

When war broke out with France there was no true commander of the British army.

Duke of York

When he was sixteen the King sent him to Berlin

to study the art of war under the famous Frederick the Great.

The Duke of York was born in London in 1763.

When he was six months old, his father secured his election as Prince-Bishop of Osnabruck in

Lower Saxony. He received this title because the prince-electors of Hanover (which included his father) were entitled

to select every other holder of this title, and the King apparently decided to ensure the title remained in the family for as

long as possible. At only 196 days of age he is therefore listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the youngest bishop in

history. He was invested as Knight of the Most Honourable Order of Bath in 1767 and as a Knight of the

Order of the Garter in 1771. When he was sixteen the King sent him to Berlin to study the art of

war under the famous Frederick the Great.

Duke of York was more administrator and reformer than commander

in the field. For example he restored the discipline and morale in the British officer corps, manual exercises were revised,

medical services were improved, he reduced the number of infantry regiments but made the battalions of uniform strength,

formed depot companies etc. etc.

In 1809 due to indiscretions by his mistress who had been corruptly selling

commissions, the Duke of York was forced to resign. He was replaced with Sir David Dundas, who was old and much less

effective in office than the Duke. The Duke was reinstated in 1811. (Haythorntwaite -

"Wellington's Infantry (1)" p 9)

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington

Wellington raised the reputation of the British

to a level unknown since Marlborough.

The Duke of Wellington has rather a mixed reputation in his home country of Ireland, where he is generally

seen as being British instead of being Irish. He was a member of The Ascendancy, the Anglo-Irish - and largely Protestant -

aristocracy of Ireland which was generally hated by the Irish Catholic majority.

Wellington came from a titled English Protestant family long settled in Ireland. His father was the Earl of Mornington.

Until his early 20s, Arthur showed no signs of distinction. His mother placed him in the army, saying

"What can I do with my Arthur?" He became a nobleman playboy, carousing and gambling.

The Duke of Wellington has rather a mixed reputation in his home country of Ireland, where he is generally

seen as being British instead of being Irish. He was a member of The Ascendancy, the Anglo-Irish - and largely Protestant -

aristocracy of Ireland which was generally hated by the Irish Catholic majority.

Wellington came from a titled English Protestant family long settled in Ireland. His father was the Earl of Mornington.

Until his early 20s, Arthur showed no signs of distinction. His mother placed him in the army, saying

"What can I do with my Arthur?" He became a nobleman playboy, carousing and gambling.

In 1787 his mother and his brother Richard purchased for Arthur a commission in the 73rd Regiment. After receiving military

training in Britain, he attended the Military Academy of Angers in France.. (Arthur also learned fluent French there.)

He campaigned in India, Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and France. Wellington rose to prominence eventually reaching the rank of field marshal.

He raised the reputation of the British to a level unknown since Marlborough.

Wellington won over French marshals at Talavera, Salamanca and Vittoria.

Several times however he was forced to full retreat, and some of his sieges failed.

Wellington was the almost perfect response to the aggressive French strategy and tactics.

The Duke, nicknamed Fabius Cunctator (the Delayer), took a very long term view and never lost sight of that.

He evaded the enemy by manoeuvre, wearing them down, avoided battles until certain of a desisive victory.

Wellington has often been portrayed as a defensive general, even though many

of his battles were offensive (Oporto, Salamanca, Toulouse, Vitoria). The Iberian peninsula

however "provides some of the best defensive ground in the world, and he was not slow to take advantage

of it." (- wikipdia.org Jan 2008)

Wellington was the almost perfect response to the aggressive French strategy and tactics.

The Duke, nicknamed Fabius Cunctator (the Delayer), took a very long term view and never lost sight of that.

He evaded the enemy by manoeuvre, wearing them down, avoided battles until certain of a desisive victory.

Wellington has often been portrayed as a defensive general, even though many

of his battles were offensive (Oporto, Salamanca, Toulouse, Vitoria). The Iberian peninsula

however "provides some of the best defensive ground in the world, and he was not slow to take advantage

of it." (- wikipdia.org Jan 2008)

Under Wellington the British army was one of the most successful armies of the Napoleonic Wars.

It was especially efficient when fed properly (to keep the discipline) and deployed on

a strong defensive position.

Wellington was the most successful British general of the period. Majority of the other British commanders (with only 1 or 2 exceptions)

were failures in independent command. Even General Moore lost. He was driven into the sea by the French, then killed, and his troops fled to Britain.

As a general Wellington is often compared to the Marlborough, with whom he shared many characteristics,

chiefly a transition to politics after a highly successful military career. He served as the Tory Prime Minister on two separate occasions,

and was one of the leading figures in the House of Lords until his retirement in 1846.

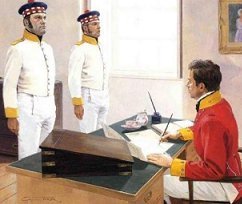

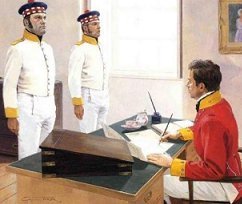

Privates and Officers.

The French were surprised by the rigid class lines

that divided the British soldiers from their officers.

There is a record of Wellington coming upon aristocratic officers

making their men carry them over a river.

Wellington ordered the soldiers to drop them on the spot.

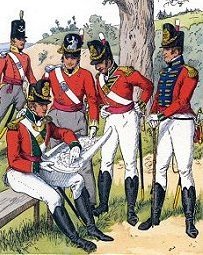

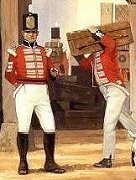

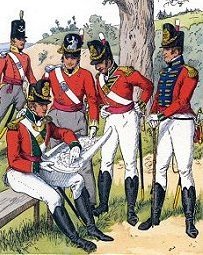

Left: Officer of the 9th Foot on Martinique in 1793.

Source: Philip Haythorntwaite.

Left: Officer of the 9th Foot on Martinique in 1793.

Source: Philip Haythorntwaite.

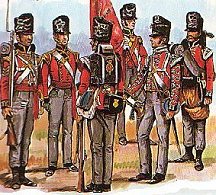

Right: officers of British infantry in 1815.

Picture by Knotel.

The soldierly profession, badly paid and subject to the harshest discipline, was not greatly appreciated in England -

was, in fact, a decidedly proletarian vocation.

It was no accident that a high percentage of

those who enlidsted were Irish since Ireland, overpopulated as it was with a deeply

impoverished peasantry, had always been one of the major providers of cannon fodder to His

Majesty's army. Irishmen generally made up between 20 % and 40 % of the infantry that

Wellington marshaled at Waterloo.

The French were surprised by the rigid class lines that divided the soldiers from their

officers and generals. Majority of the officers were all upper-class, some were sons of

clerks or shopkeepers, and the soldiers, who were from the working class, obeyed them

without question. (Barbero - "The Battle" p 22)

According to Philip Haythorntwaite there is a record of Wellington coming upon

aristocratic officers making their men carry them over a river. Wellington ordered the soldiers to drop them on the spot.

Picture: Officer of the 9th Foot on Martinique in 1793. Source: Philip Haythorntwaite

The vast majority of soldiers came from the ranks of the otherwise unemployed, men who had

not found another way to earn a living. Half of the troops had been farm laborers and the

rest textile workers or apprentice tradesmen.

In England, the proletarian origins of the soldiers opened a chasm between them and their officers and generals. It is no surprising

that Wellington said that the army was recruited from among "the scum of the earth".

He laso made remark on the significant difference between the composition of a French army

(based on conscription) and that of a British one: "The conscription calls out a share of

every class - no matter whether your son or my son - all must march."

In England, the proletarian origins of the soldiers opened a chasm between them and their officers and generals. It is no surprising

that Wellington said that the army was recruited from among "the scum of the earth".

He laso made remark on the significant difference between the composition of a French army

(based on conscription) and that of a British one: "The conscription calls out a share of

every class - no matter whether your son or my son - all must march."

Costello described his comrades: "Our men, during the war, might be said to have been composed of 3 classes.

One was zealous and brave to absolute devotion, but who, apart from their 'fighting duties', considered some little

indulgance as a right; the other class barely did their duty when under the eye of their superior; while the third, and I am happy to say, by far the smallest in number, were skulkers and poltroons

- their excuse was weakness from want of rations; they would crawl to the rear, and were seldom seen until after a battle had been fought ..."

(Costello - "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" p 121)

The soldiers of Moore's army were described as "They were all, however, volunteers … The average age of the soldiers was 23, and

their average height 5'6". Most had been farm labourers, many from impoverished

villages of Ireland and Scotland. They were paid 1 shilling per day, and led by an

officer corps of aristocrats and gentlemen, many of whom had simply bought their commissions"

(Summerville - "March of Death" p 26)

During campaign the emotions of British soldiers were divided between the hatred and contempt officially

directed at the French and Buonaparte" by British newspapers and public opinion and the

admiration they felt for the French emperor in their hearts, almost in spite of themselves.

Captain Mercer of the Royal Artillery admitted that deep down he "had often longed to see

Napoleon, that mighty man of war - that astonishing genius who had filled the world with his

renown."

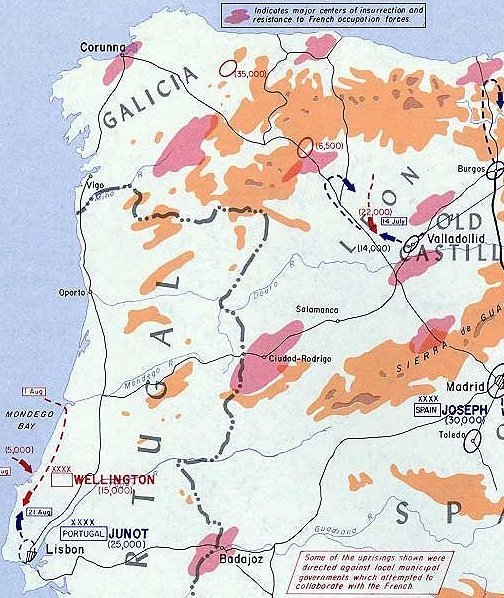

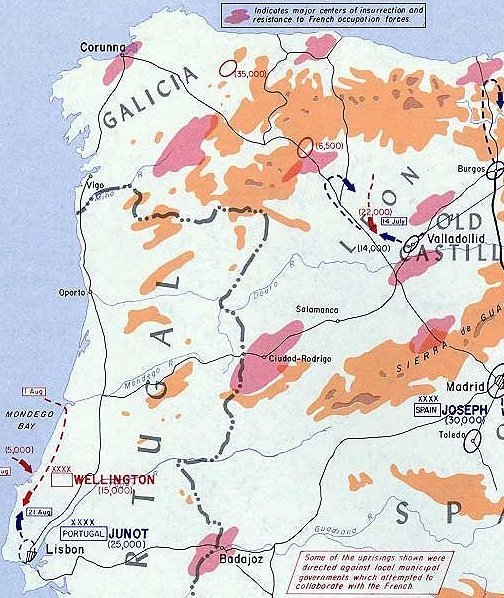

Strength and Deployment of the British army.

The dilemma for military planners was how to use

the forces for three different purposes:

home defence against possible invasion from France,

garrisoning and defence of the empire,

and rapid deployment of an expeditionary force.

In 1790s the British army consisted of the following troops:

- 30 regiments of cavalry (3+7 guard, 6 dragoons and 14 light dragoons)

- 88 infantry battalions (7 guard and 81 infantry)

- 4 foot artillery battalions and 1 Invalid Battalion (all 10 companies each)

(There were also 2 companies in India, and 1 Company of Cadets.

Two troops of the Royal Horse Artillery were in the process of organizing.

There were also 6 field and 1 invalid companies of the Royal Irish Artillery.)

In January 1805 the British army consisted of 161,800 regulars:

- 124,500 Infantry

- 17,000 Artillery and Engineers

- 20,300 Cavalry

The dilemma for military planners was how to use the forces for three different purposes:

home defence against possible invasion from France, garrisoning and defence of the empire,

and rapid deployment of an expeditionary force for any continental European war.

In January 1805 the British troops were deployed as follow:

- 66,000 stationed in England

- 34,000 in Ireland

- 22,500 in East Indies and Ceylon

- 15,300 in West Indies and Jamaica

- 6,500 on Malta (ext. link)

- 4,500 in Gibraltar (ext. link)

- 4,200 in Canada

According to Adjutant-General's returns, in the military force of Great Britain in 1808 was as follow:

- 170,000 infantry and 6,000 Foot Guards

- 30,000 cavalry

- 14,000 artillery

According to William Napier, of these, approx. 55,000 were employed in India,

the reminder were disposable, "because from 80 to 100,000 militia, differing from

the regular troops in nothing but the name, were sufficient for the home duties."

Training and Quality of the British army.

"The glory of the British army is based principally

upon its excellent discipline,

and upon the cool and sturdy courage of the people.

Indeed we know of no other troops as well disciplined."

- General Foy

Training of the British troops was on high level. The rank and file were mainly volunteers. In contrast the French were mainly recruits

and hastily trained. "Unlike the British trooper who received a minimum of 6 months'

training most French troopers received after 1805 a bare 2 to 3 weeks, being lucky if

they were taught basic horsemanship and drill." (P.J.C. Elliot-Wright)

France was not separated by water from her enemies and was forced to have massive land armies

and have it quick. War followed war with little time in between for training. In contrast

the British could simply embark their troops and leave, and this

is what they did so many times.

Britain was the wealthiest country in the world with

relatively small army. They could afford high ratio of practice rounds per soldier in

life fire training:

1. British 'Rifles' - 60 rounds and 60 blanks per man

2. Prussian jägers and Schützen - 60 rounds per man (in 1811-1812)

3. British light infantry - 50 rounds and 60 blanks

4. Prussian fusiliers (light infantry in line regiments) - 30 rounds

5. British line infantry - 30 rounds

6. Austrian line infantry - 10 rounds (in 1809)

7. Austrian line infantry - 6 rounds (in 1805)

8. Russian infantry - 6 and less rounds

The British army was based on the well tried and tested regimental system.

The esprit de corps of the regimental system was maintained in the names and titles of

regiments handed down through history, with a tradition of courage and tenacity in battle.

Their discipline and bravery on the battlefield were well known.

Let me give you an example: "Though hotly engaged at the time, I determined to watch their

movements. The 88th Foot

[Irish] next deployed into line, advancing all the time towards their opponents, who seemed to wait very coolly for them.

When they had approached to within 300 or 400 yards, the French poured in a volley or I should say a running fire from right

to left. As soon as the British regiment had recovered the first shock, and closed their

fles on the gap it had made, they commenced advancing at double time until within 50 yards nearer to the enemy, when they halted and in turn gave a running fire from their whole line, and without a moment's pause cheered and charged up the hill against them.

The French meanwhile were attempting to reload. But being hard pressed by the Briish, who allowed them

no time to give a second volley, came immediately to the right about, making the best of their way to the village."

(Costello - "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" p 125)

The British army was an excellent army but far from the most successful in overall terms.

The only British overall military success of the period was in Spain.

Most other British operation were a failure: Flanders in 1793-94; Holland in 1799; Buenos

Aires twice; Holland in 1809; the Dardenelles in 1807; Egypt in 1806; Spain and Sweden in

1808; Naples and Hanover in 1805; Spain and Italy in 1800.

The redcoats went against Washington and won at Bladensburg and North Point but suffered heavier losses to US forces made up largely

of militia. The British at New Orleans had six excellent Peninsular regiments

(4th, 7th, 43d, 44th, 85th, and 95th Rifles) and failed spectacularly against the Americans.

The outcome of New Orleans is good evidence of a good army being led badly.

In 1793-1794 the British troops in Holland received "scathing criticism from

foreign military observers and Allied commanders.

There were damning comments on the appalling behaviour of

officers, their lack of care for their men and their generally drunken demeanour.

The Army as a whole showed up badly in the field. The drill manuals were out of date, the

battalions were of poor quality ..." (Haythornthwaite - "Wellington's Infantry (1)" p 6)

The war in Spain was also not a litghtining campaign. In 1809 the British corps under

general Moore fled before Napoleon to the sea. "The track was littered for mile after mile with discarded equipment and knapsacks,

and the forlorn dead and dying." (Haythorntwaite - "Wellington's Infantry (1)" p 36)

According to popular author, Jac Weller, none of Wellington's battles

in Spain can be called "great." At Salamanca he failed to exploit his success and the

enemy quickly recovered. The battle of Fuentes de Onoro and especially at Talavera were

near disasters. According to Weller the Battle of Busaco was "a technical defeat although

claimed as victory" and the allignement of troops at Talavera was not very well thought.

Weller wrote that "if Talavera was a victory because the French withdrew then Busaco was a

defeat because the British were forced to withdraw." For the French the Battle of Corunna

is a victory, for the British this is also a victory, but the Spanish considered this battle

as a definite French victory (They called it the Battle of Elvina). Of all the bigger battles

only Salamanca was the one where Wellington not deliberately set out to fight "at that place

and at that time." Majority of the sieges were failures for Wellington. The siege of Burgos

was a very costly defeat.

The French commanders had a good opinion about Wellington's troops.

General Maximilien Foy (1775-1825) wrote:

"Their skill and intrepidity in braving the dangers of the ocean have always been unrivalled.

Their restless disposition, and fondness for travelling fit them for the wandering life of the

soldier; and they possess that most valuable of all qualities in the field of battle -

coolness in their strife. The glory of the British army is based principally upon its excellent discipline,

and upon the cool and sturdy

courage of the people. Indeed we know of no other troops as well disciplined....

In conclusion it may be said, that the English army surpasses other nations in discipline,

and in some particulars of internal management ..."

The French commanders had a good opinion about Wellington's troops.

General Maximilien Foy (1775-1825) wrote:

"Their skill and intrepidity in braving the dangers of the ocean have always been unrivalled.

Their restless disposition, and fondness for travelling fit them for the wandering life of the

soldier; and they possess that most valuable of all qualities in the field of battle -

coolness in their strife. The glory of the British army is based principally upon its excellent discipline,

and upon the cool and sturdy

courage of the people. Indeed we know of no other troops as well disciplined....

In conclusion it may be said, that the English army surpasses other nations in discipline,

and in some particulars of internal management ..."

But also in the same time the British army was one of the slower armies in Europe (except the Light Division

and cavalry). French General Thiebault writes that the scattered state of the French army in Spain

rendered its situation desperate, and that the slowness of Sir Arthur Wellesley saved it several times.

The French troops were known for their skills of extracting provisions locally - much to

the annoyance of local population.

Wellington writes: "It is certainly astonishing that the enemy [French] have been able

to remain in this country so long; and it is extraordinary instance of what a French army

can do. ... With all our money and having in our favour the good inclinations of the

country, I assure you that I could not maintain one division in the district in which they

have maintained not less than 60,000 men and 20,000 animals for more than two months."

Gates writes: "In contrast, the Allies, particularly the British, seem to have been peculiarly inept at surviving

without plenty of supplies. Even in times of minor food shortages, indiscipline erupted on a vast scale. The British divisions went to pieces in the lean

days after Talavera for example - and as late as the Waterloo campaign of 1815, we find Wellington

commenting to his Prussian friends that 'I cannot

separate from my tents and supplies. My troops must be well kept and well supplied in camp

..."

Gates writes: "In contrast, the Allies, particularly the British, seem to have been peculiarly inept at surviving

without plenty of supplies. Even in times of minor food shortages, indiscipline erupted on a vast scale. The British divisions went to pieces in the lean

days after Talavera for example - and as late as the Waterloo campaign of 1815, we find Wellington

commenting to his Prussian friends that 'I cannot

separate from my tents and supplies. My troops must be well kept and well supplied in camp

..."

In the very end of the battle of Waterloo, Wellington and Blucher decided together that the Prussians alone would continue the pursuit. This decision is usually explained by citing the exhausted condition of Wellington's infantry, but Blucher's were surely no less tired. More likely the choice reflected the plodding management and slowness of movement that characterized British troops. [Professor A. Barbero]

In the beginning of the 1815-Campaign the Prussians got 3/4 of their men to the right place at the right time, Wellington

only miserable 1/3 of his total forces. Prussian officer Müffling asked Wellington why

the Brits advance so slowly and Wellington explained: "Do not press me on this, for

I tell you, it cannot be done. If you knew the composition of the British Army and its

habits better, then you would not talk to me about that. I cannot leave my tents and supplies

behind. I have to keep my men together in their camp and supply them well to keep order and

discipline." [Peter Hofscshroer] (The Irishmen however could live on little nourishment,

they outmarched the English who had the habits "of good eating and plenty of it too.")

John Mills of British Regiment of 'Coldstream Guard' wrote: "Their (French) movements compared

with ours are as mail coaches to dung carts. In all weathers and at all times the French are accustomed to

march, when our men would fall sick by hundreds ..." The Spaniards reproached the British for the tardiness of

their marches.

"Clumsy, unintelligent, and helpless as the British soldier is when thrown upon his own

resources, or when called upon to do the duty of light troops, nobody surpasses him in a

pitched battle where he acts in masses... The fire of British infantry is delivered with such

a coolness, even in the most critical position, that it surpasses, in effect, that of any

other troops. ... This solidity and tenacity in attack and defense, form the great redeeming

quality of the British army, and have alone saved it from many a defeat, well-merited and all

but intentionally prepared by the incapacity of its officers, the absurdity of its

administration, and the clumsiness of its movements."

("The Armies of Europe" in Putnam's Monthly, No. XXXII, published in 1855)

Discipline in the British Army.

Some French deserters who joined

the British Army in the Peninsula

promptly deserted from it because

they found discipline too severe.

According to French veterans the English soldiers obeyed blindly, if they commited a fault,

they were punished with the whip. England was still the country where a person could be

sentenced to death for any one of more than 60 different crimes, and where women were

hanged every day for the theft of a piece of fruit. (Barbero - "The Battle" p 23)

In the weeks before Waterloo, several sentences of this type were carried out in public,

to the disgust of the Belgian citizenry.

For the British soldier himself discipline was invariably harsh and enlistement was for

long time.

Some French deserters who joined the British Army in the Peninsula

promptly deserted from it because they found discipline too severe. Some punishments included ‘riding the wooded horse’

a sharp-backed frame on which the offender sat astride, sometimes with weights attached to

his feet to increase discomfort.

Generally offenders were flogged on the bare back for a

variety of offences, and shot or hanged for more serious ones.

Generally offenders were flogged on the bare back for a

variety of offences, and shot or hanged for more serious ones.

According to Wellington flogging was absolutely essential to control "the scum of the earth."

He defended the harsh discipline, arguing that the army contained a proportion of

blackguards who could not be kept in line in any other way, while reformers maintained that it dishonoured both the

victim and the army in which he served. Discipline in the

Russian army was also harsh.

During march the discipline in the British army was strict, the soldiers were only allowed to quit the ranks if they were ill or if they

needed to relieve themselves. Before doing so they had to obtain a ticket or certificate

from the sergeant on approval of their company commander. Officers and senior NCOs of light

infantry carried whistles suspended on chains on the fronts of their shoulder belts.

Edward Costello gives some colorful descriptions of the punishment.

"The men being from different regiments, and under the command of a foreigner, some availed themselves of what they considered a fair opportunity of pilfering from

the country people as we pursued our march, and I am sorry to say that drunkenness and robbery were not unfrequent.

The German officer, as is usual under such circumstances, experienced great difficulty in keeping the skulkers

and disorderly from lingering in the rear. ... I was in the act of taking the jug of wine from my lips, when a party of the

16th Light Dragoons rode up and made us prisoners; the peasant, from whom the wine had been

taken, having made his complaint at headquarters. We were imprisoned, nine of us in number, in Viseu.

The second day, the Hon. Captain Pakenham, of the Adjutant-General's department, paid us a visit, and told us he had great difficulty in saving us from

being hanged. Although this was probably said to frighten, still it was not altogether a joke, as a man

of the name Maguire of the 27th Foot Regiment, who had been with me in hospital, was hung for stopping and robbing a

Portuguese of a few vintems.

As it was, the German officer in charge of the detachment received orders,

on leaving Viseu, to see that we received two dozen each from the Provost-Marshal every morning,

until we rejoined our regiments. ... The following day, the 8 culprits and myself were summoned during a halt, to appear before the German, expecting to be punished.

We were, however, agreeably deceived by the officer addressing us as follows, to the best

of my recollecton, in broken English: 'I have been told to have you mens flogged, for a crime dat is very bad and disgraceful to de soldier -

robbing de people you come paid to fight for.

But we do not flog people in my country, so I shall not flog you,

it not being the manner of my people; I shall give you all to your Colonels; if they like to flog you

, they may.' Being thus relieved, each of us saluted the kind German and retired.

From that moment, I have always entertained a high respect for our Germans ..."

(Costello - "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" pp 23-24)

Costello also described the punishment of the popular Tom Plunket. "Although Tom was a general favorite, and his conduct had resulted from the madness of intoxication, his insubordination was

too glaring to stand a chance of being passed over. He was brought to a regimental court-martial, found guilty, and sentenced to be

reduced to the ranks, and to receive 300 lashes. Poor Plunket, when he had recovered his reason, after the commission of his crime, had experienced and expressed the most unfeigned contrition, so that when

sentence became known, there was a general sorrow felt for him throughout the regiment,

particularly on account of the corporal punishment...

The square was formed for punishment: there was a tree in the centre to which the culprit

was to be tied, and close to which he stood with folded arms and downcast eyes, in front of his guard. ... The sentence was

read by the adjutant in a loud voice. Poor Tom, who had the commiseration of the whole regiment, looked deadly

pale... Happily this wretched scene was destined to a brief termination: at the 35th lash, the Colonel ordered

punishment to cease, and the prisoner taken down." (- Costello, pp 12-14)

After the Napoleonic Wars was published an article about the punishment in the British army.

"There is one institution in the British army which is perfectly sufficient

to characterize the class from which the British soldier is recruited. It is the

punishment of flogging. Corporal punishment does not exist in the French, the Prussian,

and several of the minor armies. Even in Austria, where the greater part of the recruits

consist of semi-barbarians, there is an evident desire to do away with it; thus the punishment

of running the gauntlet has recently been struck out from the Austrian military code.

After the Napoleonic Wars was published an article about the punishment in the British army.

"There is one institution in the British army which is perfectly sufficient

to characterize the class from which the British soldier is recruited. It is the

punishment of flogging. Corporal punishment does not exist in the French, the Prussian,

and several of the minor armies. Even in Austria, where the greater part of the recruits

consist of semi-barbarians, there is an evident desire to do away with it; thus the punishment

of running the gauntlet has recently been struck out from the Austrian military code.

In England, on the contrary, the cat-o'-nine-tails is maintained in its full efficiency -

an instrument of torture fully equal to the Russian knout in its most palmy time. Strange to

say, whenever a reform of the military code has been mooted in Parliament, the old martinets

have stuck up for the cat, and nobody more zealously than old Wellington himself.

To them, an unflogged soldier was a monstrously misplaced being...

This explains two very curious facts: first, the great number of English deserters before

Sebastopol. In winter, when the British soldiers had to make superhuman exertions to guard

the trenches, those who could not keep awake for forty-eight or sixty hours together, were

flogged ! The idea of flogging such heroes as the British soldiers had proved themselves in

the trenches before Sebastopol, and in winning the day of Inkermann in spite of their generals

! " ("The Armies of Europe" in Putnam's Monthly, No. XXXII, published in 1855)

Deserters and Lost Colors.

One return stated that during 1807-1809

the army suffered a high figure of 17.237 deserters.

The troops under Wellington were one of the best Britain ever had. Wellington's victories in Peninsula brought a measure of prestige to the British army, and increased reputation in the eyes of Europeans.

The British troops however were not super-humans, they - for example - were not immune to

deserterion, incl. even the most prestigious units.

In 1813 1,336 men were serving in this regiment and almost 10 % of them deserted.

This is estimated that 1/9 of those called into the Army of the Reserve and 1/5 of

those enlisted deserted. One return stated that during 1807-1809 the army suffered a

high figure of 17.237 deserters. Mind you, the British soldiers were mostly volunteers,

not conscripts, like the French.

The British troops under Moore however were run out of Spain, discipline was lost,

there was looting and straggling, as well as dead and intoxicated bodies marking their

line or retreat. The only thing that held firm and showed a bold front during the retreat

was the rear guard.

So a British army did fall apart in the field during the period.

Below: English deserters during the Napoleonic wars (source: Charles Dupin):

1805 - 6.497

1806 - 4.466

1807 - 5.021

1808 - 5.059

1809 - 4.186

1810 - 3.994

1811 - 4.060

1812 - 4.353

1813 - 5.822

1814 - 8.857

To the English deserters (given above) can be also added those who deserted from the

foreign troops serving in the British army; Brunswickers, Hannoverians,

Spaniards and others, increasing the total number. Sometimes the Spanish guerillas caught the deserters from British and German units and brought them back.

"At the time I speak of we had a man in our regiment [95th Rfles] of the name of Stratton, who, after robbing several of his comrades of trifling articles, took it into his head to desert to the enemy,

and was detected in the act, in a wood that leads from Rodrigo to Salamanca, by the vigilant Guerillas, and brought back prisoner to our cantonments.

He was tried by a regimental court-martial, and sentenced to receive 400 lashes."

(- Costello p 118)

Edward Costello of 95th Rifles described what sometimes happened

when the deserters were caught. "I now have to relate one of those melancholy incidents

peculiar to a soldier's life, that occurred

while we remained at El Bodon. On taking Rodrigo we had captured, among others, 10 men

who had deserted from our division. These were condemned to be shot. The place of execution

was on a plain near Ituera, where our division was drawn up, forming three sides of a square;

the culprits, as usual, being placed in front of a trench, dug for a grave, on the vacant side.

Two of the deserters, the one man of the same company as myslef [of 95th Rifles], named Hudson ... had been persuaded into the

rash step, were pardoned on the ground. The other, a corporal, named Cummins, of the 52nd Regiment, and who had been mainly

instrumental, I believe, in getting the others to desert with him, was placed on the fatal ground in a wounded state.

... This man was pardoned also. Why he was pardoned I cannot say. ... A large trench had been dug as a grave for the wretched men who were to suffer.

Along the summit of the little heap of mould that had been thrown up from the pit, the deserters were placed in a row, with their eyes bandaged ...

Some of the pooor fellows, from debility, were unable to kneel, and lay at their length, or crouched up into an attitude of despair, upon the loose earth.

The signal to the firing party was given by a motion of the provost's cane, when the culprits were all hurried together into eternity, with the

exception of one man of the 52nd Foot, who strange to say, remained standing and untouched. His countenance, that before had been deadly pale, now exhibited a bright flush.

Perhaps he might have imagined himself pardoned; if so however, he was doomed to be miserably deceived, as the following minute two men of the reserve came up and fired their pieces into his bosom, when giving a loud scream, that had a very

horrible effect upon those near, he sprang forward into his grave." (Costello - "The

Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" p 86)

The French captured several colors of Wellington's infantry.

The French captured several colors of Wellington's infantry.

In Spain the King's Color of II/48th Regiment of Foot was captured by French NCO Dion d'Aumont from the 10th Hussar Regiment.

The regimental color of the 48th Northamptonshire was also claimed by the French.

The II/66th Foot Regiment lost 2 Colors captured by the French.

At Talavera NCO Legout-Duplesis of 5th Dragoon Regiment took 4 British colors.

One British color was captured by the French at Almeida.

At Albuera Polish ulans and French hussars captured 6 British colors.

At Albuera Polish ulans and French hussars captured 6 British colors.

At Salamanca French Ltn. Gullinat of the 118th Line Regiment captured

British color.

In 1814 the French took 4 British Colors at Bergen op Zoom. These were from

the I/4th Foot King’s Own and the II/69th South Lincolnshire.

American historian John Elting writes: "Amazingly, at Waterloo the French had lost only 2 eagles, and those

early in the battle to English cavalry." By contrast, they had taken either 4 or

6 colors - the number naturally is much disputed - from Wellington's army."

There are known at least names of three troopers who captured these Colors:

- one seized by Marechal de Logis Gauthier (Gautier) of the 10th Cuirassier Regiment

- one by Fourier Palau of the 9th Cuirassier Regiment

- one by unknown cuirassier of the 8th Cuirassier Regiment [He captured the Color of the British 69th Foot Regiment, GdD Kellermann to MdE Davout, 24th June 1815, Arch.Serv.Hist.]

General Delort mentions an English Color captured by an NCO of the 9th Cuirassier Regiment

- one by Capitaine Klein de Kleinenberg from the Chasseurs of the Guard [he captured one Color of the KGL, GdD Leefebvre-Desnouettes to Drouot, 23rd June 1815, Arch. Serv.Hist.]

During battle the captured colors were brought to and deposited in the farm of Le Caillou, farmhouse Napoleon had been using for his headquarters. Unfortunately during the retreat after battle the trophies were left there.

|

British Army of the Napoleonic Wars

British Army of the Napoleonic Wars

"The history of England is similar to the history of Britain before the arrival of the Saxons. It begins in the prehistoric

during which time Stonehenge was erected. At the height of the Roman Empire Britannia and Wales was under the rule of the

Romans. ... In 1066, the Normans (Normandy is a region in northern France) invaded and conquered England.

(Battle of Hastings -->)

"The history of England is similar to the history of Britain before the arrival of the Saxons. It begins in the prehistoric

during which time Stonehenge was erected. At the height of the Roman Empire Britannia and Wales was under the rule of the

Romans. ... In 1066, the Normans (Normandy is a region in northern France) invaded and conquered England.

(Battle of Hastings -->)

For centuries there was a rivalry between England and Spain, and between England and France.

The role of England in Iberia was coloured by the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, under which the independence

of Portugal was guaranteed. Relations with Portugal always have been closer than those with Spain, and Spain and the

United Kingdom have gone to war twice over Portugal's independence.

At the start of the Napoleonic Wars, Spain found itself allied with France, and again found itself outgunned at sea,

notably at Trafalgar. British attempts to capture parts of the Spanish colonial empire were less successful and included

failures at Buenos Aires, Puerto Rico, and the Canary Islands.

For centuries there was a rivalry between England and Spain, and between England and France.

The role of England in Iberia was coloured by the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, under which the independence

of Portugal was guaranteed. Relations with Portugal always have been closer than those with Spain, and Spain and the

United Kingdom have gone to war twice over Portugal's independence.

At the start of the Napoleonic Wars, Spain found itself allied with France, and again found itself outgunned at sea,

notably at Trafalgar. British attempts to capture parts of the Spanish colonial empire were less successful and included

failures at Buenos Aires, Puerto Rico, and the Canary Islands.

Picture: cartoon of Prime Minister of Great Britain, William Pitt, and Royal

Navy expecting the French invasion.

Picture: cartoon of Prime Minister of Great Britain, William Pitt, and Royal

Navy expecting the French invasion.

The English newspapers were full of articles and caricatures

about "Buonaparte", to cheer up the people. It has been the greatest alarm ever known in the

city of London and an intense invasion panic in the entire country.

Major-General William Napier writes: "The uninterrupted success that, for so many years, attended the arms of Napoleon, gave him a moral influence doubling his actual force. Exciting at once terror, admiration, and hatred, he

absorbed the whole attention of an astonished world, and, openly or secretly, all men acknowledged the power of his genius; the continent bowed before him, and in England an increasing number of absurd and virulent libels on his person and character indicated the

growth of secret fear." (Napier - “History of the War in Peninsula 1807-1814” p 101)

The English newspapers were full of articles and caricatures

about "Buonaparte", to cheer up the people. It has been the greatest alarm ever known in the

city of London and an intense invasion panic in the entire country.

Major-General William Napier writes: "The uninterrupted success that, for so many years, attended the arms of Napoleon, gave him a moral influence doubling his actual force. Exciting at once terror, admiration, and hatred, he

absorbed the whole attention of an astonished world, and, openly or secretly, all men acknowledged the power of his genius; the continent bowed before him, and in England an increasing number of absurd and virulent libels on his person and character indicated the

growth of secret fear." (Napier - “History of the War in Peninsula 1807-1814” p 101)

The struggle between Great Britain and France was not David versus Goliath as some

English authors suggest.

Great Britain was a strong, very wealthy country.

In a period between the 1770s and 1820s, Britain experienced an accelerated process of economic change that

transformed a largely agrarian economy into the world's first industrial economy. This phenomenon is known as

the "industrial revolution", since the changes were all embracing and permanent.

The wool trade was one of the major industries and the country exported wool to Europe.

By the 17th century England was a leader in textile production.

British factories processed the colonial goods and sold them on in both the quickly growing domestic market

or abroad. London was, and still is, major financial district of Britain, and one of the world's leading financial centres.

The struggle between Great Britain and France was not David versus Goliath as some

English authors suggest.

Great Britain was a strong, very wealthy country.

In a period between the 1770s and 1820s, Britain experienced an accelerated process of economic change that

transformed a largely agrarian economy into the world's first industrial economy. This phenomenon is known as

the "industrial revolution", since the changes were all embracing and permanent.

The wool trade was one of the major industries and the country exported wool to Europe.

By the 17th century England was a leader in textile production.

British factories processed the colonial goods and sold them on in both the quickly growing domestic market

or abroad. London was, and still is, major financial district of Britain, and one of the world's leading financial centres.

History proves that although she declaimed so loudly against France's grasping spirit, she has since acquired more

territory than she ever charged him with conquering.

British forces invaded Cape Cod, plans were drafted to capture the Spanish province of

Chile and link up with Argentine and Sir Wellesey "was to be asked to invade Spanish held

Mexico". It seems like the continuous wars benefited Britain very well:

History proves that although she declaimed so loudly against France's grasping spirit, she has since acquired more

territory than she ever charged him with conquering.

British forces invaded Cape Cod, plans were drafted to capture the Spanish province of

Chile and link up with Argentine and Sir Wellesey "was to be asked to invade Spanish held

Mexico". It seems like the continuous wars benefited Britain very well:

French colonial empire was the second largest in the world.

(The story of France's colonial empire truly began in 1605 and its peak was between 1919 and 1939).

French colonial empire was the second largest in the world.

(The story of France's colonial empire truly began in 1605 and its peak was between 1919 and 1939).

The British army came into being with the merger of the Scottish Army and the English Army,

following the unification of the two countries' parliaments and the creation of the United Kingdom

of Great Britain in 1707. Under Oliver Cromwell, the army had been active in the re-conquest,

settlement and suppressing revolts in Ireland.

The army and navy, in building the Empire, fought Netherlands, Spain, France, and United States for supremacy in

North America, Africa and West Indies. It also battled many native tribes.

The British army came into being with the merger of the Scottish Army and the English Army,

following the unification of the two countries' parliaments and the creation of the United Kingdom

of Great Britain in 1707. Under Oliver Cromwell, the army had been active in the re-conquest,

settlement and suppressing revolts in Ireland.

The army and navy, in building the Empire, fought Netherlands, Spain, France, and United States for supremacy in

North America, Africa and West Indies. It also battled many native tribes.

The king was the nominal commander of the British army.

The coming of George III to the throne brought the first British born king for 50 years.

His predecessor, King George I, was a German who did not speak a word of English,

but was Protestant. So he started the rule of the House of Hanover, under whom Britain

achieved wealth.

The king was the nominal commander of the British army.

The coming of George III to the throne brought the first British born king for 50 years.

His predecessor, King George I, was a German who did not speak a word of English,

but was Protestant. So he started the rule of the House of Hanover, under whom Britain

achieved wealth.

The Duke of Wellington has rather a mixed reputation in his home country of Ireland, where he is generally

seen as being British instead of being Irish. He was a member of The Ascendancy, the Anglo-Irish - and largely Protestant -

aristocracy of Ireland which was generally hated by the Irish Catholic majority.

Wellington came from a titled English Protestant family long settled in Ireland. His father was the Earl of Mornington.

Until his early 20s, Arthur showed no signs of distinction. His mother placed him in the army, saying

"What can I do with my Arthur?" He became a nobleman playboy, carousing and gambling.

The Duke of Wellington has rather a mixed reputation in his home country of Ireland, where he is generally

seen as being British instead of being Irish. He was a member of The Ascendancy, the Anglo-Irish - and largely Protestant -

aristocracy of Ireland which was generally hated by the Irish Catholic majority.

Wellington came from a titled English Protestant family long settled in Ireland. His father was the Earl of Mornington.

Until his early 20s, Arthur showed no signs of distinction. His mother placed him in the army, saying

"What can I do with my Arthur?" He became a nobleman playboy, carousing and gambling.

Wellington was the almost perfect response to the aggressive French strategy and tactics.

The Duke, nicknamed

Wellington was the almost perfect response to the aggressive French strategy and tactics.

The Duke, nicknamed

Left: Officer of the 9th Foot on Martinique in 1793.

Source: Philip Haythorntwaite.

Left: Officer of the 9th Foot on Martinique in 1793.

Source: Philip Haythorntwaite. In England, the proletarian origins of the soldiers opened a chasm between them and their officers and generals. It is no surprising

that Wellington said that the army was recruited from among "the scum of the earth".

He laso made remark on the significant difference between the composition of a French army

(based on conscription) and that of a British one: "The conscription calls out a share of

every class - no matter whether your son or my son - all must march."

In England, the proletarian origins of the soldiers opened a chasm between them and their officers and generals. It is no surprising

that Wellington said that the army was recruited from among "the scum of the earth".

He laso made remark on the significant difference between the composition of a French army

(based on conscription) and that of a British one: "The conscription calls out a share of

every class - no matter whether your son or my son - all must march."

The French commanders had a good opinion about Wellington's troops.

General Maximilien Foy (1775-1825) wrote:

"Their skill and intrepidity in braving the dangers of the ocean have always been unrivalled.

Their restless disposition, and fondness for travelling fit them for the wandering life of the

soldier; and they possess that most valuable of all qualities in the field of battle -

coolness in their strife. The glory of the British army is based principally upon its excellent discipline,

and upon the cool and sturdy

courage of the people. Indeed we know of no other troops as well disciplined....

In conclusion it may be said, that the English army surpasses other nations in discipline,

and in some particulars of internal management ..."

The French commanders had a good opinion about Wellington's troops.

General Maximilien Foy (1775-1825) wrote:

"Their skill and intrepidity in braving the dangers of the ocean have always been unrivalled.

Their restless disposition, and fondness for travelling fit them for the wandering life of the

soldier; and they possess that most valuable of all qualities in the field of battle -

coolness in their strife. The glory of the British army is based principally upon its excellent discipline,

and upon the cool and sturdy

courage of the people. Indeed we know of no other troops as well disciplined....

In conclusion it may be said, that the English army surpasses other nations in discipline,

and in some particulars of internal management ..."

Gates writes: "In contrast, the Allies, particularly the British, seem to have been peculiarly inept at surviving

without plenty of supplies. Even in times of minor food shortages, indiscipline erupted on a vast scale. The British divisions went to pieces in the lean

days after Talavera for example - and as late as the Waterloo campaign of 1815, we find Wellington

commenting to his Prussian friends that 'I cannot

separate from my tents and supplies. My troops must be well kept and well supplied in camp

..."

Gates writes: "In contrast, the Allies, particularly the British, seem to have been peculiarly inept at surviving

without plenty of supplies. Even in times of minor food shortages, indiscipline erupted on a vast scale. The British divisions went to pieces in the lean

days after Talavera for example - and as late as the Waterloo campaign of 1815, we find Wellington

commenting to his Prussian friends that 'I cannot

separate from my tents and supplies. My troops must be well kept and well supplied in camp

..."

Generally offenders were flogged on the bare back for a

variety of offences, and shot or hanged for more serious ones.

Generally offenders were flogged on the bare back for a

variety of offences, and shot or hanged for more serious ones.

After the Napoleonic Wars was published an article about the punishment in the British army.

"There is one institution in the British army which is perfectly sufficient

to characterize the class from which the British soldier is recruited. It is the

punishment of flogging. Corporal punishment does not exist in the French, the Prussian,

and several of the minor armies. Even in Austria, where the greater part of the recruits

consist of semi-barbarians, there is an evident desire to do away with it; thus the punishment

of running the gauntlet has recently been struck out from the Austrian military code.

After the Napoleonic Wars was published an article about the punishment in the British army.

"There is one institution in the British army which is perfectly sufficient

to characterize the class from which the British soldier is recruited. It is the

punishment of flogging. Corporal punishment does not exist in the French, the Prussian,

and several of the minor armies. Even in Austria, where the greater part of the recruits

consist of semi-barbarians, there is an evident desire to do away with it; thus the punishment

of running the gauntlet has recently been struck out from the Austrian military code.

The French captured several colors of Wellington's infantry.

The French captured several colors of Wellington's infantry. At Albuera Polish ulans and French hussars captured 6 British colors.

At Albuera Polish ulans and French hussars captured 6 British colors.

Picture: the Lincolnshires in combat, by Keith Rocco.

Picture: the Lincolnshires in combat, by Keith Rocco.

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

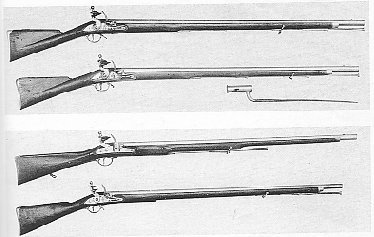

Picture: British infantry muskets.

Source: Brent Nosworthy - "With Musket,

Cannon, and Sword."

Picture: British infantry muskets.

Source: Brent Nosworthy - "With Musket,

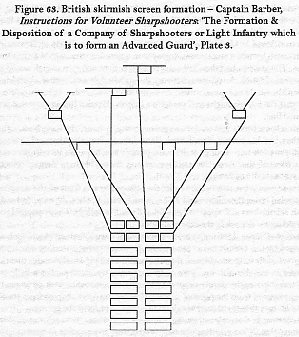

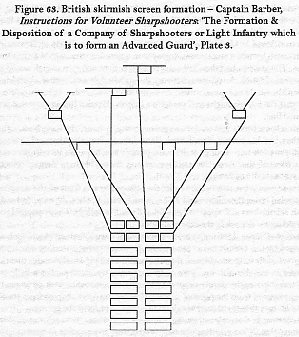

Cannon, and Sword." The British batalion column was always formed with a frontage of one company.

With a column at open distance the gaps between the rear rank of the leading company

and the rear rank of the next one was the same as the company frontage; say 20-25 m.

The British batalion column was always formed with a frontage of one company.

With a column at open distance the gaps between the rear rank of the leading company

and the rear rank of the next one was the same as the company frontage; say 20-25 m.

Red coat is a term often used to refer to British infantryman, because of the colour of the uniforms formerly worn

by the majority of regiments. In 1645, the Parliament passed the New Model Army ordinance. The infantry regiments wore

coats of Venetian red with white facings. ("There is no basis for the historical myth that red coats were favoured because

they did not show blood stains. Blood does in fact show on red clothing as a black stain." - wikipedia.org)

Red coat is a term often used to refer to British infantryman, because of the colour of the uniforms formerly worn

by the majority of regiments. In 1645, the Parliament passed the New Model Army ordinance. The infantry regiments wore

coats of Venetian red with white facings. ("There is no basis for the historical myth that red coats were favoured because

they did not show blood stains. Blood does in fact show on red clothing as a black stain." - wikipedia.org)

"Despite the best efforts of Sir John Moore, when it came to choosing a new uniform in which to fight,

conservativeness won the day. While the 95th Rifles were permitted to adopt the green clothing and black leather

equipment of the German regiments in British service, the Light Infantry regiments were ordered to conform to the

regulations for light companies - retaining red jackets." (- http://www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regts/the_rifles/)

"Despite the best efforts of Sir John Moore, when it came to choosing a new uniform in which to fight,

conservativeness won the day. While the 95th Rifles were permitted to adopt the green clothing and black leather

equipment of the German regiments in British service, the Light Infantry regiments were ordered to conform to the

regulations for light companies - retaining red jackets." (- http://www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regts/the_rifles/)

Left: British Foot Guards in 1815, by Knotel.

From left to right:

Left: British Foot Guards in 1815, by Knotel.

From left to right: The British well-drilled regulars were humiliated by American farmers, militia and Indians

fighting in lose order. The american experience made a profound impact and resulted in

tactical and organizational changes in the British army.

But still the quality of the British skirmishers (except the 60th and 95th Regiment) was

below their French counterparts.

The British well-drilled regulars were humiliated by American farmers, militia and Indians

fighting in lose order. The american experience made a profound impact and resulted in

tactical and organizational changes in the British army.

But still the quality of the British skirmishers (except the 60th and 95th Regiment) was

below their French counterparts.

In the end of 1797 the parliament authorised the formation of a 5th battalion of the

60th Foot to be recruited from German exiles familiar with the use of rifles.

These Germans were armed with rifles designed primarily for hunting, were slow loading

and required cleaning every few shots.

In the end of 1797 the parliament authorised the formation of a 5th battalion of the

60th Foot to be recruited from German exiles familiar with the use of rifles.

These Germans were armed with rifles designed primarily for hunting, were slow loading

and required cleaning every few shots.

Left: baby-faced captain of 95th Rifles.

Left: baby-faced captain of 95th Rifles.

Picture: British infantry by Knotel of Germany.

Picture: British infantry by Knotel of Germany.  Picture: the Highlanders, by Dmitrii Zgonnik of Ukraine.

Picture: the Highlanders, by Dmitrii Zgonnik of Ukraine.