|

Best Cavalry Regiments.

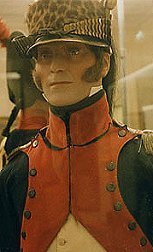

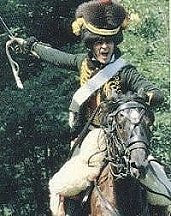

Picture: Hussar. "Napoleon's Cavalry

Recreated in Color Photographs" by Maughan

Picture: Hussar. "Napoleon's Cavalry

Recreated in Color Photographs" by Maughan

The light cavalry enjoyed reputation for bravery and an uninhibited joie-de-vivre

when not. There were many excellent regiments of light cavalry, including the 1st

Husards, 2nd Husards, 5th Chasseurs-a-Cheval or any of the lancer regiments.

NCO Guindey of 10th Hussars killed Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia.

NCO Pawlikowski of Vistula Uhlans captured Prince Liechtenstein.

The heavy cavalry was not worse.

In 1809 arriving at Ratisbon, the 2nd Cuirassiers took part in a fight with the Austrian

Merveldt Uhlan Regiment first and then against the Hohenzollern and Ferdinand Cuirassier

Regiments.

Charged three times, the Austrians were routed, the 2nd Cuirassiers took 200 prisoners

fortified in a village.

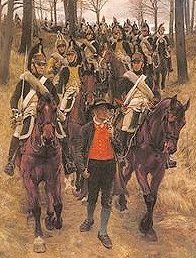

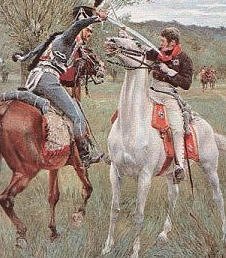

In Spain the French dragoons and chasseurs had their hands full with the Spanish guerillas and the

British cavalry. Costello of British 95th Rifles writes: "... a loud cheering to the right attracted our attention, and we perceived

our 1st Dragoons charge a French cavalry regiment. As this was the first charge of cavalry most of us had ever seen, were were

all naturally much interested on the occassion. The French skirmishers who were also extended against us seemed to partiicipate in the same feeling

as both parties suspended firing while the affair of dragoons was going on. The English and the French cavalry met in the most gallant

manner, and with the greatest show of resolution. The first shock, when they came in collision, seemed terrific, and many men and horses fell on both sides. They had ridden through and past each other,

and now they wheeled round again. This was followed by a second charge, accompanied by some very pretty- sabre-practice, by which many saddles were emptied, and

English and French chargers were soon galloping about the field without riders. These immediately occupied the attention of the French skirmishers and ourselves, and we were soon engaged in pursuing them, the men of each nation endeavouring

to secure the chargers of the opposite one as legal spoil. While engaged in this chase we frequently became intermixed, when much laughter

was indulged in by both parties at the different accidents that occured in our pursuit."

(Costello - "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" p 67)

Lancers.

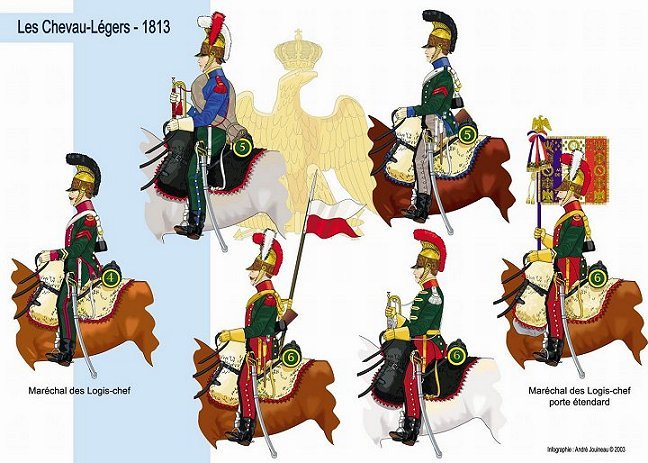

6e Regiment de Chevaulegers-Lanciers

4 Battle Honors: 1812 - La Moskowa, 1813 - Hanau, 1814 - Champaubert, 1815 - Fleurus

16 Battles:

1812 - Krasnoe, Smolensk, Valoutina, La Moskowa, Wiasma, Beresina,

1813 - Jauer, Leipzig, Hanau,

1814 - Champaubert, Montmirail, Vauchamps, Arcis-sur-Aube, Saint-Dizier,

1815 - Fleurus, Waterloo

Note: This regiment was formed in 1811, from the 29e Regiment de Dragons

1er Regiment de Vistule Lanciers (In 1811 the "Vistula Uhlans" were

renamed to 7e Lanciers)

0 Battle Honors: it was not French unit so no battle honors. The French 20e Dragoons

were awarded with battle honor for Albuera, but not the Vistula Uhlans who took at

this battle 5-6 British colors, destroyed British infantry brigade, and captured hundreds of prisoners.

44 Battles: 1798 - Sessa, 1800 - Hohenlinden, 1806 - Naples, Gaete, 1807 -

Strigau, Dantzi, Saltzbrun, 1808 - Tudela,

Mallen, Alagon, Saragosse, Almaraz, 1809 - Guadalajara, Jevenes, Ciudad-Real, Santa-Cruz,

Alenbillas, Talavera, Almonacid, Santa Maria de Nieva, Ocana, 1810 - Sierra Morena, Baza,

Arquillos, Orgas, Tortosa, Almanzor and Lorca, 1811 - Cor, Albuera, Olivenza, Baza, Berlanga,

1813 - Magdebourg, Naumbourg, Bautzen, Dresden, Pirna, Leipzig, Hanau, 1814 - Montereau,

Neuilly-Saint-Front, Chalons, Chartres

Note: The uhlans defeated Prussians at Strigau, Austrians at Hohenlinden,

at Mallen and Tudela trounced the Spaniards, at Albuera and Talavera routed the British,

in 1813 it was turn for the Russians. No other light cavalry regiment participated in

so many combats, in so different terrain and climate, took so many Colors and prisoners and fought even after Napoleon;s abdication. NCO Pawlikowski of Vistula Uhlans captured Prince Liechtenstein. During the Siege of Saragossa they climbed down from their saddles and stormed the entrenched enemy camp.

The 1st Vistula Uhlans were nicknamed

"The Picadors of the Hell."

8e Regiment de Chevaulegers-Lanciers

4 Battle Honors: 1812 - Polotzk, 1813 - Bautzen, Dresden, 1814 - Champaubert

9 Battles:

1812 - Jakubowo, Polotsk, La Beresina,

1813 - Lutzen, Bautzen, Kulm, Dresden, Leipzig,

1814 - Champaubert

Note: This brave regiment existed only 2.5 years. It was formed in May 1811, from the 2e Regiment de Vistula Lanciers which had been

formed in France (not in Poland). In January 1814 this regiment was disbanded.

Colonels:

Baron Lubienski, general in 1814

Hussars.

2e Regiment de Hussards

4 Battle Honors: 1798 - Honschoote, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Friedland, 1809 - Medellin

45 Battles:

1792 - Grisvelle, Verton, La Croix-aux-Bois, Grand-Pre, Montcheutin, Valmy, Jemmapes,

1793 - La Roche, Hondschoote, Landrecies, Wissembourg, Edelsheim,

1794 - Marolles, Fleures, Mons, Anderhoven,

1795 - Capture of Dutch Fleet at Texel

(ext.link), Schwalbach, Kreutznach,

1796 - Burg Eberach,

1797 - Passage of the Rhine at Neuwied

1799 - Mannheim, Engen, Hirchberg,

1800 - Dillerich, Bopfingen, Kelheim, Germersheim,

1803 - Nienberg,

1805 - Austerlitz,

1806 - Halle, Crewitz, Mohrungen,

1807 - Osterode, Friedland,

1809 - Medllin, Alcabon,

1810 - Ronda, Sierra de Cazala,

1811 - La Gerboa, Los Santos Albuhera,

1812 - Somanis,

1813 - Leipzig,

1814 - Montereau,

1815 - Belfort

4e Regiment de Hussards

5 Battle Honors: 1794 - Fleurus, 1800 - Hohenlinden, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Friedland, 1813 - Sagonte

36 Battles:

1792 - Valmy, La Croix-aux-Bois,

1793 - Maestricht, Aldenhoven, Tirlemont, Hondschoote, Wattingnies,

1794 - Fleures,

1795: Langenheim,

1796 - Blockade of Mayence,

1797 - Passage of the Rhine Neuwied,

1799 - Altiken, Winterthur, Zurich,

1800 - Neubourg, Ampfingen, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Austerlitz,

1806: Jena, Lubeck,

1807 - Liebstadt , Mohrungen,

1809 - Alcanitz, Belchite,

1811 - Stella, Chiclana, Sagonte,

1813 - Yecla, Col d'Ordal,

1813 - Gross Beeren, Leipzig,

1814 - Lons-le-Saulnier, Saint Georges, Lyon,

1815 - Ligny, Waterloo

5e Regiment de Hussards

5 Battle Honors: 1792 - Jemmapes, 1806 - Jena, 1809 - Eckmuhl, 1812 - Borodino,

1813 - Hanau

32 Battles:

1792 - Valmy, Jemmapes (as 6th Hussar Regiment),

1793 - Wattignies,

1794 - Blockade of Nimegue,

1795 - Capture of Dutch Fleet at Texel

(ext.link),

1797 - Neuwied,

1799 - Ostrach, Stockach,

1800 - Mosskirch, Biberach, Kirchberg, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Austerlitz, 1806 - Crewitz, Stettin, Golymin, 1807 - Waltersdorf,

Eylau, Heilsberg, Konigsberg, 1809 - Eckmuhl, Wagram, 1812 - Borodino, Winkono,

Berezina, 1813 - Bautzen, Leipzig, Hanau, 1814 - Arcis-sur-Aube, 1815 - Ligny, Waterloo,

Versailles

Note: This regiment was part of the legendary 'Hellish Brigade' under General Lasalle.

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1793 - Ruin,

1794 - Scholtenius,

1794 - Schwartz,

1806 - Dery,

1809 - Meuziau,

1813 - Fournier,

1814 - Liegeard

7e Regiment de Hussards

5 Battle Honors: 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Heilsberg, 1812 - Borodino, 1813 - Hanau, 1814 - Vauchamps

51 Battles:

1793 - Pirmasens,

1794 - Treves, Grevenmachen, Siege of Mayence,

1795 - Mannheim,

1796 - Bopfingen, Neubourg, Villingen, Siege of Kehl, Lichtenau,

1798 - Soleure, Berne, Coure, Einsieden,

1800 - Engen, Nesselwangen, Feldkirch, Salzbourg,

1805 - Mariazell, Affleng, Austerlitz, 1806 - Gera, Zehbenick, Prentzlow,

Stettin, Lubeck, Czenstowo ?, Golymin, 1807 - Eylau, Heilsberg, Konigsberg, 1809 - Peising,

Ratisbone, Raab, Wagram, Znaim, 1812 - Vilna, Smolensk, Ostrowno, Borodino,

1813 - Borna, Altenbourg, Leipzig, Hanau, 1814 - Vauchamps, Montereau, Reims, Laon, Paris

1815 - Fleurus, Waterloo

Note: This regiment was part of the legendary 'Hellish Brigade' under General Lasalle.

In 1806 member of this regiment captured Color of Prussian Queen's Dragoon Regiment.

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1792 - Lamothe,

1792 - Boyer,

1794 - Marisy,

1803 - Rapp,

1803 - Marx,

1806 - Colbert,

1809 - Custine,

1810 - Eulner,

1814 - Marbot

Chasseurs.

5e Regiment de Chasseurs-à-Cheval

4 Battle Honors: 1799 - Zurich, 1800 - Hohenlinden, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Friedland

86 Battles:

1792 - Valmy ,

1793 - Pellemberg, Bliebech, Corblech, Dunkerque, Propinghen, Honschoote, Furnes,

1794 - Lannoy, Tournai, Mont-Cassel, Tourcoing, Pont-à-Chin, Zonnebech, Hooglede, Oudenarde, Gand, Alost, Breda,

Boxtel, Passage of the Meuse, Nimegue,

1795 - Driel, Nieuw-Schanz,

1796 - Camp de Mulheim, Cologne,

1797 - Mayennce,

1798 - Ostende, Herenthals, Breda,

1799 - Ettlingen, Zurzach, Andelfigen, Zurich, Bussingen-Bergan,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Biberach, Ochsenbrunn, Abach, Werth,

1805 - Munich, Wasserbourg, Haag, Austerlitz,

1806 - Schleiz, Furstenberg, Waren, Crewitz, Lubeck,

1807 - Morhungen, Lobau, Krentzberg, and Friedland,

1808 - Pont d'Alcolea, Baylen, Burgos, Somosierra (?), Pont d'Almaras,

1809 - Medellin, Torrigos, Talevera,

1810 - Cadiz, 1812 - Bornos, 1813 - Alembra, El-Coral, Caracuel, Olmeda, Hilesca, Burgos,

Vittoria,

1813 - Juterbock, Dennewitz, Mockern, La Partha, Leipzig, Hanau,

1814 - Orthez and Toulouse, 1814 - Remagen, La Chaussee, Mormant, Troyes, Bar-sur-Aube,

Sommepuis, Saint- Dizier

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1791 - Chevalier de Lameth ,

1792 - Monard,

1793 - Richardot,

1793 - De la Noue,

1793 - Poichet dit Prudent,

1800 - Corbineau,

1806 - Bonnemains,

1811 - Baillot,

1814 - Duchastel

22e Regiment de Chasseurs-à-Cheval

5 Battle Honors: 1805 - Ulm, Austerlitz, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Eylau, Friedland

39 Battles:

1805 - Enns, Botzen, Wischau, Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena, Waren, Lubeck,

1807 - Hoff, Eylau, Guttstadt, Heilsburg, Friedland,

1808 - Medina-del-Rio-Seco, Niou, Burgos,

1809 - Hoya, Benavente, Pont-Vedra, Salamanque,

1810 - Astagora,

1811 - Sabugal,

1812 - Arapiles, Pancorbo, Torquemada, Burgos,

1813 - Vittoria, Gross-Beeren, Luchenwald, Wittenburg, Juterbock, Bautzen, Monasterio (Spain), Leipzig,

1814 - Montereau, Orthez, Saint-Dizier, Joigny, Toulouse

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1800 - Latour-Maubourg,

1805 - Bordessoule,

1807 - Pieton-Premale,

1808 - Michel dit Defosses

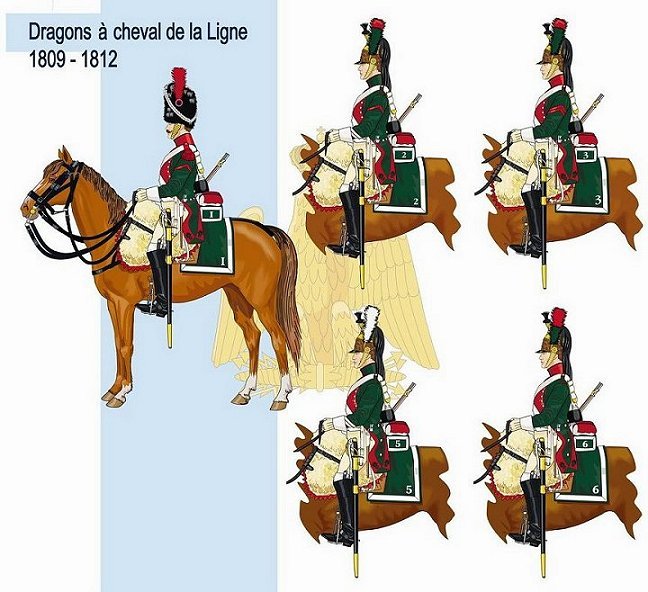

Dragoons.

20e Regiment de Dragons

4 Battle Honors: 1798 - Les Pyramides, 1806 - Jena, 1807 - Friedland, 1811 - Albuhera

54 Battles:

1793 - Siege of Quesnoy,

1794 - Landrecies, Quesnoy, Valenciennes, Aldenhoven,

1796 - Mondovi, Lodi, Castiglone,

1797 - La Favorite, Saint-Georges, Due-Castelli, Castelluchio, Mantoue,

1798 - Alexandrie, Chebreiss, les Pyramides,

1799 - El-Arich, Gaza, Jaffa, Saint-Jean-d'Acre, Mont-Tabor, Aboukir,

1800 - Heliopolis,

1805 - Wertingen, Memmingen, Neresheim, Ulm, Austerlitz,

1806 - Jena and Pultusk, 1807 - Eylau, Heilsberg, Friedland,

1808 - Andujar and Tudela, 1809 - Ucles, Ciudad-Real, Almonacid, Ocana, Salamanca, Pampelune, Tamames,

1811 - Albuera, 1813 - Leipzig, Dresden, and Hanau, 1814 - S.Dizier, Brienne, La Rothiere,

Mormont, Monterau, Troyes, 1815 - Ligny, Waterloo

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1793 - Gontran ,

1797 - Boussart,

1800 - Reynaud,

1807 - Corbineau,

1811 - Desargus,

1815 -Briqueville

Cuirassiers and carabiniers

1er Regiment de Cuirassiers

4 Battle Honors: 1792 - Jemmapes, 1805 - Austerlitz, 1807 - Eyau, 1812 - Borodino

49 Battles:

1792: Jemmapes, Anderlecht, Tirelemont,

1793: Maestricht, La Roer, Nerwinden, Maubeuge,

1794: Mouscron, Pont-a-Chin, Rousselar, Maline,

1796: Rivoli, Tagliament,

1799: Le Trebbia, La Secchia, Novi, Genola,

1800: Mozambano,

1801: San-Massiano, Verone,

1805: Wertingen, Ulm, Hollabrunn, Raussnitz, Austerlitz,

1806: Jena, Lubeck,

1807: Hoff, Eylau,

1809: Eckmuhl, Ratisbonne, Essling, Wagram, Hollabrunn, Znaim,

1812: La Moskowa, Winkowo,

1813: Katzbach, Leipzig, Hanau, Hambourg,

1814: La Chausee, Vauchamps, Bar-sur-Aube, Sezanne, Valcourt,

1815: Ligny, Genappe, Waterloo

Note: In 1791 the regiment was named the 1er Regiment de Cavalerie, in

1801 became the 1er Regiment de Cavalerie-Cuirassiers, and in 1803 became the 1er Regiment

de Cuirassiers.

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1791 - de Clermont-Tonnerre,

1792 - Deschamps de la Varenne,

1793 - Doncourt,

1793 - Maillard,

1795 - Severac,

1797 - Juignet,

1798 - Margaron,

1803 - Guiton,

1805 - de Berckheim,

1809 - Clerc,

1814 - de la Mothe Guery,

1815 - Ordener

1er Regiment de Carabiniers-à-Cheval

0 Battle Honors:

42 Battles:

1792 - Valmy,

1793 - Arlon, Bliecastel, Climbach, Wissembourg,

1794 - Tourcoing, Tournay,

1795 - Frankenthal, Mannheim, Biberach,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Augsbourg, Blenheim, Passage of the Danube, Hochstett, Neresheim, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Nurembourg, Austerlitz,

1806 - Prentzlow, Lubeck, 1807 - Ostrolenka, Guttstadt, Friedland,

1809 - Eckmuhl, Ratisbonne, Essling, and Wagram, 1812 - Borodino, Winkowo, Wiazma,

1813 - Dresden, Leipzig, and Hanau, 1814 - Montmirail, La Guillotiere, Troyes, Craonne, Laon,

Reims, 1815 - Waterloo

Colonels and chef-de-brigade:

1791 - Valence,

1791 - Meillonas,

1792 - Berruyer,

1792 - Antoine,

1792 - Baget,

1793 - Jaucourt-Latour,

1795 - Girard,

1799 - Cochois,

1805 - Prince Borghese,

1807 - Laroche,

1813 - De Bailliencourt,

1815 - Roge

2e Regiment de Carabiniers-à-Cheval

0 Battle Honors:

42 Battles:

1792 - Valmy,

1793 - Arlon, Bliecastel, Climbach, Wissembourg,

1794 - Tourcoing, Tournay,

1795 - Frankenthal, Mannheim, Biberach,

1800 - Engen, Moeskirch, Augsbourg, Blenheim, Passage of the Danube, Hochstett, Neresheim, Hohenlinden,

1805 - Nurembourg, Austerlitz,

1806 - Prentzlow, Lubeck, 1807 - Ostrolenka, Guttstadt, Friedland,

1809 - Eckmuhl, Ratisbonne, Essling, and Wagram, 1812 - Borodino, Winkowo, Wiazma,

1813 - Dresden, Leipzig, and Hanau, 1814 - Montmirail, La Guillotiere, Troyes, Craonne, Laon,

Reims, 1815 - Waterloo

Battle Honors

1790 - 1815 |

hussars |

chasseurs |

lancers

formed in 1811 |

dragoons |

cuirassiers |

| 7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 5 |

4e Hussards

5e Hussards

7e Hussards |

22e Chasseurs

-

- |

-

-

- |

-

-

- |

-

-

- |

| 4 |

1er Hussards

2e Hussards

3e Hussards

4e Hussards

6e Hussards

8e Hussards

9e Hussards

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- |

1er Chasseurs

4e Chasseurs

5e Chasseurs

6e Chasseurs

8e Chasseurs

9e Chasseurs

11e Chasseurs

14e Chasseurs

18e Chasseurs

19e Chasseurs

21e Chasseurs

-

-

-

-

-

- |

4e Lanciers

5e Lanciers

6e Lanciers

8e Lanciers

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- |

1er Dragons

2e Dragons

3e Dragons

4e Dragons

5e Dragons

8e Dragons

9e Dragons

10e Dragons

11e Dragons

12e Dragons

20e Dragons

21er Dragons

22e Dragons

23e Dragons

24e Dragons

25e Dragons

26e Dragons |

1er Cuirasiers

2e Cuirassiers

3e Cuirassiers

4e Cuirassiers

5e Cuirassiers

6e Cuirassiers

7e Cuirassiers

8e Cuirassiers

9e Cuirassiers

10e Cuirassiers

11e Cuirassiers

-

-

-

-

-

- |

| Battles and Combats |

regiments |

| 86 |

5e Chasseurs-a-Cheval |

| 54 |

20e Dragons |

| 51 |

7e Hussards |

| 50 |

10e Chasseurs-a-Cheval |

| 49 |

9e Hussards

1er Cuirassiers |

| 48 |

12e Chasseurs-a-Cheval |

| 47 |

3e Hussards

2e Chasseurs-a-Cheval |

| 45 |

2e Hussards |

| 44 |

1er Hussards

Vistula Uhlans |

| 42 |

1er Carabiniers

2e Carabiniers

|

|

The force of impact generated by cavalry, provided it was engaged at the proper moment, was out of all

proportion to its numbers. Had this not been the case, after all, governments would not have spent so much money on

maintaining mounted troops, which represented a heavy cost to the national treasury.

A single cavalry regiment consumed 4 metric tons of fodder every day.

The force of impact generated by cavalry, provided it was engaged at the proper moment, was out of all

proportion to its numbers. Had this not been the case, after all, governments would not have spent so much money on

maintaining mounted troops, which represented a heavy cost to the national treasury.

A single cavalry regiment consumed 4 metric tons of fodder every day.

Albert-Jean-Michel de Rocca writes: "The various troops that composed our army, especially the cavalry and infantry, differed extremely in manners and habits. The infantrymen, having only to think of themselves and their muskets, were selfish, great talkers, and great sleepers.

... They were apt to dispute with their officers, and sometimes they were even insolent to

them ... They forgot all their hardships the moment they heard the sound of the enemy's first gun.

Albert-Jean-Michel de Rocca writes: "The various troops that composed our army, especially the cavalry and infantry, differed extremely in manners and habits. The infantrymen, having only to think of themselves and their muskets, were selfish, great talkers, and great sleepers.

... They were apt to dispute with their officers, and sometimes they were even insolent to

them ... They forgot all their hardships the moment they heard the sound of the enemy's first gun.

In the cavalry served more nobles than in any other branch of the army.

Majority of the aristocratic officers left France during Revolution and

the overall quality of French cavalry had fallen badly.

It was Napoleon who made it as an effective force which would have

parity with any enemy.

In the cavalry served more nobles than in any other branch of the army.

Majority of the aristocratic officers left France during Revolution and

the overall quality of French cavalry had fallen badly.

It was Napoleon who made it as an effective force which would have

parity with any enemy.

Before the campaigns in 1805 and in 1812 the cavalrymen were intensively trained, supplied with

splendid uniforms and horses and armed to teeth. They were enthusiastic and ready to fight.

The officers and NCOs were battle hardened veterans.

In 1805 the French had established a morale ascendancy over their opponents.

Before the campaigns in 1805 and in 1812 the cavalrymen were intensively trained, supplied with

splendid uniforms and horses and armed to teeth. They were enthusiastic and ready to fight.

The officers and NCOs were battle hardened veterans.

In 1805 the French had established a morale ascendancy over their opponents.

At Borodino the French cavalry captured a redoubt, a feat never

repeated by any other cavalry. Colonel Griois watched the cavalry attack: "It would be difficult to convey our feelings as

watched this brilliant feat of arms, perhaps without equal in the military annals of nations

... cavalry which we saw leaping over ditches and scrambling up ramparts under a hail of

canister shot, and a roar of joy resounded on all sides as they became masters of the redoubt."

Meerheimb wrote: "Inside the redoubt, horsemen and foot soldiers, gripped by a frenzy of

slaughter, were butchering each other without any semblance of order..."

At Borodino the French cavalry captured a redoubt, a feat never

repeated by any other cavalry. Colonel Griois watched the cavalry attack: "It would be difficult to convey our feelings as

watched this brilliant feat of arms, perhaps without equal in the military annals of nations

... cavalry which we saw leaping over ditches and scrambling up ramparts under a hail of

canister shot, and a roar of joy resounded on all sides as they became masters of the redoubt."

Meerheimb wrote: "Inside the redoubt, horsemen and foot soldiers, gripped by a frenzy of

slaughter, were butchering each other without any semblance of order..."

Many regiments ceased to exist. For example the 5th Regiment of Cuirassiers had 958 men present for duty on June 15th,

1812. On Feb 1st 1813 had only 19 ! The French cavalry never recovered from the massive loss of horses.

Nine out of ten cavalrymen who survived walked much of the way home; most of those who rode did so on tiny, but tough,

Russian and Polish ponies, their boots scuffing the ground. Napoleon wrote: "I have no army any more! For many days

I have been marching in the midst of a mob of disbanded, disorganized men, who wander all over the countryside in search

of food." It is estimated that 175.000 excellent horses of cavalry and artillery

were lost in Russia !

The Russians reported burning the corpses of 123,382 horses as they cleaned up their countryside of the debris of war.

So heavy were the horse losses that one of Napoleon's most serious handicaps in the 1813 campaign was his inability

to reconstitute his once-powerful cavalry.

Many regiments ceased to exist. For example the 5th Regiment of Cuirassiers had 958 men present for duty on June 15th,

1812. On Feb 1st 1813 had only 19 ! The French cavalry never recovered from the massive loss of horses.

Nine out of ten cavalrymen who survived walked much of the way home; most of those who rode did so on tiny, but tough,

Russian and Polish ponies, their boots scuffing the ground. Napoleon wrote: "I have no army any more! For many days

I have been marching in the midst of a mob of disbanded, disorganized men, who wander all over the countryside in search

of food." It is estimated that 175.000 excellent horses of cavalry and artillery

were lost in Russia !

The Russians reported burning the corpses of 123,382 horses as they cleaned up their countryside of the debris of war.

So heavy were the horse losses that one of Napoleon's most serious handicaps in the 1813 campaign was his inability

to reconstitute his once-powerful cavalry.

The northern part of France called Normandy was one of the world biggest horse-breeding areas (Studs of Le Pin and St. Lo). Napoleon valued these mounts highly and during reviews often asked colonels how many horses from Normandy they have in their regiments. In 1810 the horse grenadiers of the Guard rode on black horses, 14 1/2 - 15 hands tall, between 4 and 4 1/2 years old and bought in the city of Caen (Normandy) for 680 francs apiece.

The German horse breeders from Hananover and Holstein and traders made fortunes as Napoleon purchased huge amounts of horses for his heavy cavalry. The Prussian large mounts were also accepted.

The northern part of France called Normandy was one of the world biggest horse-breeding areas (Studs of Le Pin and St. Lo). Napoleon valued these mounts highly and during reviews often asked colonels how many horses from Normandy they have in their regiments. In 1810 the horse grenadiers of the Guard rode on black horses, 14 1/2 - 15 hands tall, between 4 and 4 1/2 years old and bought in the city of Caen (Normandy) for 680 francs apiece.

The German horse breeders from Hananover and Holstein and traders made fortunes as Napoleon purchased huge amounts of horses for his heavy cavalry. The Prussian large mounts were also accepted.

The French cavalry was commanded by Marshal Joachim Murat. His father was farmer-inkeeper,

his mother a pious woman set on making a priest

of him. Murat was tall, athletic with a handsome face framed by dark curls.

He was "woman-crazy; Napoleon complained that he needed them like he needed food."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" p 144)

The French cavalry was commanded by Marshal Joachim Murat. His father was farmer-inkeeper,

his mother a pious woman set on making a priest

of him. Murat was tall, athletic with a handsome face framed by dark curls.

He was "woman-crazy; Napoleon complained that he needed them like he needed food."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" p 144)

In combat Murat was supreme. Britten-Austin writes: "Riding out in front of a line of red and white pennons which stretches

from the Dwina's swamp on the right to the island of forest in the centre, he intends to harangue the Polish lancer division

- but finds himself in a most awkward, not to say comical position. The Poles need no

exhortion. With tremendous elan, like several thousand pig-stickers, they charge, driving the King

of Naples like a

In combat Murat was supreme. Britten-Austin writes: "Riding out in front of a line of red and white pennons which stretches

from the Dwina's swamp on the right to the island of forest in the centre, he intends to harangue the Polish lancer division

- but finds himself in a most awkward, not to say comical position. The Poles need no

exhortion. With tremendous elan, like several thousand pig-stickers, they charge, driving the King

of Naples like a  Murat fled to Corsica after Napoleon's fall. During an attempt to regain Naples through an insurrection in

Calabria, he was arrested by the forces of his rival, Ferdinand IV of Naples.

Murat was told to move towards the place destined for his execution,

an officer gave him a handkerchief to blind himself, but he refused it.

Murat arrived at the destined spot, turning immediately his face to the soldiers, and placing his hand upon his breast, he

gave the word “Fire.” The soldiers fired 12 shots at his breast, which killed him instantaneously, and 3 in the head after he fell.

Murat was buried in a pit where they throw the most despicable felons.

Murat fled to Corsica after Napoleon's fall. During an attempt to regain Naples through an insurrection in

Calabria, he was arrested by the forces of his rival, Ferdinand IV of Naples.

Murat was told to move towards the place destined for his execution,

an officer gave him a handkerchief to blind himself, but he refused it.

Murat arrived at the destined spot, turning immediately his face to the soldiers, and placing his hand upon his breast, he

gave the word “Fire.” The soldiers fired 12 shots at his breast, which killed him instantaneously, and 3 in the head after he fell.

Murat was buried in a pit where they throw the most despicable felons.

The carabiniers were raised in 1691 by Louis XIV (The Sun King), with the men drafted

from the better troopers of other line regiments. Rene Chartrand writes: "Commissions in the

carabiniers could not be purchased, but were granted by the king to deserving

and talented officers of modest means. ... In principle, carabiniers were to fight on foot

when required, which they occasionally did, notably when they dismounted, stormed and captured

the gates of Prague in 1741 .

The carabiniers were raised in 1691 by Louis XIV (The Sun King), with the men drafted

from the better troopers of other line regiments. Rene Chartrand writes: "Commissions in the

carabiniers could not be purchased, but were granted by the king to deserving

and talented officers of modest means. ... In principle, carabiniers were to fight on foot

when required, which they occasionally did, notably when they dismounted, stormed and captured

the gates of Prague in 1741 .

In 1809 the carabiniers suffered badly in the hands of

Austrian uhlans and Napoleon ordered to give them armor.

Chlapowski, among others, described this combat: "The cuirassier division arrived, with the brigade of carabiniers at its

head. ... Soon an uhlan regiment in six squadrons trotted up to within 200 paces of the

carabiniers and launched a charge at full tilt.

It reached their line but could not break it, as the second regiment of carabiniers was

right behind the first, and behind it the rest of the cuirassier division. I saw a great many

carabiniers with lance wounds, but a dozen or so uhlans had also fallen."

(Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p 60)

In 1809 the carabiniers suffered badly in the hands of

Austrian uhlans and Napoleon ordered to give them armor.

Chlapowski, among others, described this combat: "The cuirassier division arrived, with the brigade of carabiniers at its

head. ... Soon an uhlan regiment in six squadrons trotted up to within 200 paces of the

carabiniers and launched a charge at full tilt.

It reached their line but could not break it, as the second regiment of carabiniers was

right behind the first, and behind it the rest of the cuirassier division. I saw a great many

carabiniers with lance wounds, but a dozen or so uhlans had also fallen."

(Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p 60)

The campaign in Russia, and especially the reareat during winter, broke the backbone of the carabiniers

and they never were the same. In 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig they panicked before Hungarian hussars.

Rilliet from the 1st Cuirassiers witnessed the encounter.

The 1st Carabiniers were in front and general Sebastiani was to the right of the regiment: all at once a mass of enemy

cavalry, mainly Hungarian hussars, rode furiously down on the carabiniers. 'Bravo!' cried the general, laughing and waving

the riding crop which was the only weapon that he designed to use.

The campaign in Russia, and especially the reareat during winter, broke the backbone of the carabiniers

and they never were the same. In 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig they panicked before Hungarian hussars.

Rilliet from the 1st Cuirassiers witnessed the encounter.

The 1st Carabiniers were in front and general Sebastiani was to the right of the regiment: all at once a mass of enemy

cavalry, mainly Hungarian hussars, rode furiously down on the carabiniers. 'Bravo!' cried the general, laughing and waving

the riding crop which was the only weapon that he designed to use.

Napoleon formed cuirassiers as follow: the first twelve régiments d'Cavalerie received

the strongest and tallest men and horses. Napoleon gave them armor and they were considered

as elite troops. They were numbered 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Cuirassiers.

Napoleon formed cuirassiers as follow: the first twelve régiments d'Cavalerie received

the strongest and tallest men and horses. Napoleon gave them armor and they were considered

as elite troops. They were numbered 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Cuirassiers.

In 1812 at Borodino, the French and Saxon cuirassiers captured the Great Redoubt defended

by Russian infantry and artillery (see picture).

Chlapowski of Old Guard Lancers writes:

"The redoubt had been so ruined by cannon fire that the Emperor rightly jidged cavalry

capable of taking it. So we watched the beautiful sight of our cuirassier charge."

General Caulaincourt, with his eyes aflame with the ardor of battle, rode to the front of the cuirassiers and shouted:

"Follow me, weep not for him [Montbrun], but come and avenge his death."

In 1812 at Borodino, the French and Saxon cuirassiers captured the Great Redoubt defended

by Russian infantry and artillery (see picture).

Chlapowski of Old Guard Lancers writes:

"The redoubt had been so ruined by cannon fire that the Emperor rightly jidged cavalry

capable of taking it. So we watched the beautiful sight of our cuirassier charge."

General Caulaincourt, with his eyes aflame with the ardor of battle, rode to the front of the cuirassiers and shouted:

"Follow me, weep not for him [Montbrun], but come and avenge his death."

In reply to Murat's order to enter that redoubt right through the Russian line, he said,

"You shall soon see me there, dead or alive." The trumpets sounded the charge, and putting himself at the head

of this iron-clad cavalry, he dashed forward. The cavalrymen pressed on with sabers drawn.

Wathier's 2nd Cuirassier Division arrived at the redoubt first, and as they were about

to enter its rear they were greeted by a heavy volley from the infantry inside.

General Caulaincourt was killed. The Raievski Redoubt was captured by cavalry, a feat

never repeated !

Heinrich von Brandt writes: "I saw General Auguste de Caulaincourt, mortally wounded, being carried

away in a white cuirassier cloak, stained deep red by his blood. There, in the redoubt, the bodies of infantrymen were

scattered amongst French, Saxon, Westphalian and Polish cuirassiers uniformed in blue and in white. ...

This was a crucial moment in the battle and the firing abated a little as if both sides wondered what to do next."

In reply to Murat's order to enter that redoubt right through the Russian line, he said,

"You shall soon see me there, dead or alive." The trumpets sounded the charge, and putting himself at the head

of this iron-clad cavalry, he dashed forward. The cavalrymen pressed on with sabers drawn.

Wathier's 2nd Cuirassier Division arrived at the redoubt first, and as they were about

to enter its rear they were greeted by a heavy volley from the infantry inside.

General Caulaincourt was killed. The Raievski Redoubt was captured by cavalry, a feat

never repeated !

Heinrich von Brandt writes: "I saw General Auguste de Caulaincourt, mortally wounded, being carried

away in a white cuirassier cloak, stained deep red by his blood. There, in the redoubt, the bodies of infantrymen were

scattered amongst French, Saxon, Westphalian and Polish cuirassiers uniformed in blue and in white. ...

This was a crucial moment in the battle and the firing abated a little as if both sides wondered what to do next."

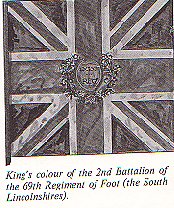

In 1815 at Quatre Bras, French cuirassiers, Private Henry and NCO Gauthire captured King's Color of the II Btn. of 69th Foot [GdD Kellermann wrote

in his report (now in S.H.A.T. C15 5) to Ney after the charge: "We took the Color of the 69th which was captured by the cuirassiers

Valgayer and Mourassin" (added with pencil by another hand: "Albisson and Henry ?").]

American historian John Elting writes: "The 69th at once ordered its regimental tailors to make up a new flag, and denied any loss.

Unfortunately, Napoleon had already announced the capture."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" p 352)

In 1815 at Quatre Bras, French cuirassiers, Private Henry and NCO Gauthire captured King's Color of the II Btn. of 69th Foot [GdD Kellermann wrote

in his report (now in S.H.A.T. C15 5) to Ney after the charge: "We took the Color of the 69th which was captured by the cuirassiers

Valgayer and Mourassin" (added with pencil by another hand: "Albisson and Henry ?").]

American historian John Elting writes: "The 69th at once ordered its regimental tailors to make up a new flag, and denied any loss.

Unfortunately, Napoleon had already announced the capture."

(Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" p 352)

Names of the French cavalrymen who captured Allies Colors:

Names of the French cavalrymen who captured Allies Colors:

In the Battle of Ligny in 1815, the commander of the Prussian army almost died under the hooves of the cuirassiers horses.

General Blücher's horse (it had been a present from the Prince Regent of England) was hit and fell to the ground trapping the commander underneath it.

His adjutant's horse was hit too.

In the Battle of Ligny in 1815, the commander of the Prussian army almost died under the hooves of the cuirassiers horses.

General Blücher's horse (it had been a present from the Prince Regent of England) was hit and fell to the ground trapping the commander underneath it.

His adjutant's horse was hit too.

On photo: French cuirassier sabre from Military Heritage

On photo: French cuirassier sabre from Military Heritage  The most known cuirassier commanders were Generals Nansouty and d'Hautpoul.

Etienne-Marie-Antoine Champion de Nansouty (1768-1815) came from aristocracy, went with the Revolution but did not put himself forward.

Nansouty was a man of tradition, education and exactitude. "His men were always carefully

trained and cared for. Yet there was no elan in his character, no readiness

for an unexpected, all-out blow to save a desperate day. His disposition was mordant ... "

( John Elting, - p 162)

The most known cuirassier commanders were Generals Nansouty and d'Hautpoul.

Etienne-Marie-Antoine Champion de Nansouty (1768-1815) came from aristocracy, went with the Revolution but did not put himself forward.

Nansouty was a man of tradition, education and exactitude. "His men were always carefully

trained and cared for. Yet there was no elan in his character, no readiness

for an unexpected, all-out blow to save a desperate day. His disposition was mordant ... "

( John Elting, - p 162)

Jean-Joseph-Ange D'Hautpoul (1754-1807) was a giant of a man, with enormous body strength.

He was a self-confident and very proud individual.

In contrast to Nansouty, d'Hautpoul was a fiery commander eager to charge at any time.

In 1794 at Aldenhoven Hautpoul crushed enemy cavalry twice as numerous and was promoted to

the rank of general.

Jean-Joseph-Ange D'Hautpoul (1754-1807) was a giant of a man, with enormous body strength.

He was a self-confident and very proud individual.

In contrast to Nansouty, d'Hautpoul was a fiery commander eager to charge at any time.

In 1794 at Aldenhoven Hautpoul crushed enemy cavalry twice as numerous and was promoted to

the rank of general.  The French cuirassiers of the Napoleonic wars wore dark blue coat, a flaming grenade

on coat-tails and saddlecloth, red epaulettes and plume attached to their headwear.

Inspections conducted in cuirassier regiments showed lack of epaulettes on big scale.

The French cuirassiers of the Napoleonic wars wore dark blue coat, a flaming grenade

on coat-tails and saddlecloth, red epaulettes and plume attached to their headwear.

Inspections conducted in cuirassier regiments showed lack of epaulettes on big scale.

During the decades before Napoleonic Wars only the dragoons were trained in infantry and

cavalry duties. General Jomini wrote: "Opinions will be always divided as to those amphibious

animals called dragoons. It is certainly an advantage to have several battalions of mounted

infantry, who can anticipate an enemy at a defile, or scour a wood; but to make cavalry out

of foot soldiers is very difficult. ... It has been said that the greatest inconvenience

resulting from the use of dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one moment to

make them believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment that a

foot soldier is superior to any horseman... But it cannot be denied, however, that great

advantages might result to the general who could rapidly move up 10,000 infantrymen on

horseback to a decisive point ..."

During the decades before Napoleonic Wars only the dragoons were trained in infantry and

cavalry duties. General Jomini wrote: "Opinions will be always divided as to those amphibious

animals called dragoons. It is certainly an advantage to have several battalions of mounted

infantry, who can anticipate an enemy at a defile, or scour a wood; but to make cavalry out

of foot soldiers is very difficult. ... It has been said that the greatest inconvenience

resulting from the use of dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one moment to

make them believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment that a

foot soldier is superior to any horseman... But it cannot be denied, however, that great

advantages might result to the general who could rapidly move up 10,000 infantrymen on

horseback to a decisive point ..."

In 1799-1800 France had 20 dragoon regiments.

In 1799-1800 France had 20 dragoon regiments.

Napoleon could mount only part of his dragoons. That fact, combined with Napoleon's modern ideas

of combining fire power and mobility, led him to the conclusion that units of foot dragoons

should be formed.

For his planned cross-Channel invasion of England, he organized two divisions of dismounted dragoons.

They were put into infantry-style shoes, gaiters and packs. They also received drums to supplement

their trumpets.

Napoleon could mount only part of his dragoons. That fact, combined with Napoleon's modern ideas

of combining fire power and mobility, led him to the conclusion that units of foot dragoons

should be formed.

For his planned cross-Channel invasion of England, he organized two divisions of dismounted dragoons.

They were put into infantry-style shoes, gaiters and packs. They also received drums to supplement

their trumpets.

In the first phase of Napoleonic Wars they served on the primary theater of war,

in Central Europe, before being sent to Spain and Italy.

The dragoons distinguished themselves in several battles.

In the first phase of Napoleonic Wars they served on the primary theater of war,

in Central Europe, before being sent to Spain and Italy.

The dragoons distinguished themselves in several battles.

The column of French dragoons halted and stood motionless like a stonewall

[kak kamennaia stiena] waiting for the enemy. The dragoons from the second rank

grabbed their muskets and began firing while these in the first rank drew sabers and waited.

The charging uhlans first slowed down and then halted. The French sounded

massive “En avant ! Vive l’Empereur!” and advanced forward en masse.

The uhlans and Cossacks gave way before the sheer weight of the column.

Their retreat was covered by flankers who opened fire on the pursuing dragoons.

The column made a half turn to the right and tried to cut off the way of retreat for the

uhlans and Cossacks.

The column of French dragoons halted and stood motionless like a stonewall

[kak kamennaia stiena] waiting for the enemy. The dragoons from the second rank

grabbed their muskets and began firing while these in the first rank drew sabers and waited.

The charging uhlans first slowed down and then halted. The French sounded

massive “En avant ! Vive l’Empereur!” and advanced forward en masse.

The uhlans and Cossacks gave way before the sheer weight of the column.

Their retreat was covered by flankers who opened fire on the pursuing dragoons.

The column made a half turn to the right and tried to cut off the way of retreat for the

uhlans and Cossacks.

After 1807 majority of the dragoons served on secondary theaters of wars, Spain and Italy.

Many of the regiments in Spain lacked uniforms, horses and equipment. For example in Spain they were dressed in the brown

cloth of the Capucines found in convents and churches. They also had difficulty in obtaining

eppaulettes for their elite companies and chin straps. For lack of sufficient number of

regulation sabers the old Toledo-swords with three edges were used.

But the dragoons were efficient troops. They fought a grim and deadly war of ambush and

retaliation against the hostile Spaniards. They guarded communication lines and escorted convoys.

After 1807 majority of the dragoons served on secondary theaters of wars, Spain and Italy.

Many of the regiments in Spain lacked uniforms, horses and equipment. For example in Spain they were dressed in the brown

cloth of the Capucines found in convents and churches. They also had difficulty in obtaining

eppaulettes for their elite companies and chin straps. For lack of sufficient number of

regulation sabers the old Toledo-swords with three edges were used.

But the dragoons were efficient troops. They fought a grim and deadly war of ambush and

retaliation against the hostile Spaniards. They guarded communication lines and escorted convoys.

One of the dragoons' greatest successes in Spain came in 1812.

The second in command of the British army, Lord Paget, as Henry William Paget was then styled, was captured by the

French dragoons.

One of the dragoons' greatest successes in Spain came in 1812.

The second in command of the British army, Lord Paget, as Henry William Paget was then styled, was captured by the

French dragoons.

In 1815 during the Waterloo Campaign there were only 15 dragoon regiments

and these fought to the very end of the war.

On 1 July (approx. half month after Waterloo) several dragoons regiments marched toward

Villacoublay. This force was screened by a small vangaurd. The vanguard met two Prussian squadrons

and was thrown back in the first clash. Behind it, however, the 5th and the 13th Dragoons deployed out of

the wood. Two Prussian regiments arrived, the (3rd) Brandenburg Hussars and (5th) Pomeranian Hussars

The dragoons were driven back and fled to the village.

In 1815 during the Waterloo Campaign there were only 15 dragoon regiments

and these fought to the very end of the war.

On 1 July (approx. half month after Waterloo) several dragoons regiments marched toward

Villacoublay. This force was screened by a small vangaurd. The vanguard met two Prussian squadrons

and was thrown back in the first clash. Behind it, however, the 5th and the 13th Dragoons deployed out of

the wood. Two Prussian regiments arrived, the (3rd) Brandenburg Hussars and (5th) Pomeranian Hussars

The dragoons were driven back and fled to the village.

After rallying the survivors Major von Wins went to report the defeat to Blucher, who was

colonel-in-chief of the (5th) Hussars. Nostitz described the scene: "... Major von Wins unexpectedly rode up and stopped.

The major dismounted ... came up to me, saying in a very excited voice, 'What you see here is all that is left

of the two hussar regiments. Everyone else is either dead or taken prisoner.' I was very surprised.

... Major von Wins ... demanded to be taken to the Prince (Blucher). I tried to stop him, telling him

his reception would be highly unpleasant. However, that did not help and I had to announce him.

The Prince heard the report in growing anger and then cried out in rage, 'Lord ! If what you are saying is true, then I wish the devil

had fetched you too !"

After rallying the survivors Major von Wins went to report the defeat to Blucher, who was

colonel-in-chief of the (5th) Hussars. Nostitz described the scene: "... Major von Wins unexpectedly rode up and stopped.

The major dismounted ... came up to me, saying in a very excited voice, 'What you see here is all that is left

of the two hussar regiments. Everyone else is either dead or taken prisoner.' I was very surprised.

... Major von Wins ... demanded to be taken to the Prince (Blucher). I tried to stop him, telling him

his reception would be highly unpleasant. However, that did not help and I had to announce him.

The Prince heard the report in growing anger and then cried out in rage, 'Lord ! If what you are saying is true, then I wish the devil

had fetched you too !"

One of the most known dragoons was Emmanuel Grouchy.

John Elting writes: " [he] was of the ancient chivalry of France,

his family acknowledged aristocracy from at least the 14th Century. ... From the first it

was clear that he was 'a horseman by nature and cavalry soldier by instinct.'

Better, he knew how to handle forces of all arms and took good care of his men.

When he was suspeneded in 1793 because he was an aristocrat, his troopers came close to

mutiny. ... Grouchy's correspondence shows a thin-skinned man, reluctant to assume

responsibility yet conscientious in discharging it. Actually he was abler than he realized.

He failed to show the necessary initiative during Waterloo but, left isolated after that

battle, managed a masterful retreat.

As a cavalryman, he was far superior to Murat in tactical skill, administrative ability,

and common sense. Clean-handed and very courageous ..."

One of the most known dragoons was Emmanuel Grouchy.

John Elting writes: " [he] was of the ancient chivalry of France,

his family acknowledged aristocracy from at least the 14th Century. ... From the first it

was clear that he was 'a horseman by nature and cavalry soldier by instinct.'

Better, he knew how to handle forces of all arms and took good care of his men.

When he was suspeneded in 1793 because he was an aristocrat, his troopers came close to

mutiny. ... Grouchy's correspondence shows a thin-skinned man, reluctant to assume

responsibility yet conscientious in discharging it. Actually he was abler than he realized.

He failed to show the necessary initiative during Waterloo but, left isolated after that

battle, managed a masterful retreat.

As a cavalryman, he was far superior to Murat in tactical skill, administrative ability,

and common sense. Clean-handed and very courageous ..."

Picture: officer of 1st Lancer Regiment in parade uniform

Picture: officer of 1st Lancer Regiment in parade uniform Before the Russian campaign Napoleon wanted to oppose the

Before the Russian campaign Napoleon wanted to oppose the  Only few lancers served in 1812 in Russia. There was however much more to do for them in 1813 in Saxony

and in 1814 in France. The French lancers fought with success at

Only few lancers served in 1812 in Russia. There was however much more to do for them in 1813 in Saxony

and in 1814 in France. The French lancers fought with success at  In 1815 at Genappe, Colonel Surd of 2e Lanciers, was badly wounded by the

In 1815 at Genappe, Colonel Surd of 2e Lanciers, was badly wounded by the  Mastery with lance required training and strong hand. "It took a lot of extra training to produce a competent lancer.

A British training manual produced some years after Waterloo stated that he had to master 55

different exercises with his lance - 22 against cavalry, 18 against infantry, with 15 general ones thrown in for good measure."

(Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 247)

Mastery with lance required training and strong hand. "It took a lot of extra training to produce a competent lancer.

A British training manual produced some years after Waterloo stated that he had to master 55

different exercises with his lance - 22 against cavalry, 18 against infantry, with 15 general ones thrown in for good measure."

(Adkin - "The Waterloo Companion" p 247)

The dragoons and the chasseurs were the most numerous French cavalry.

The horse chasseurs [chasseurs-a-cheval] were light cavalry and were often brigaded with the

hussars. The most famous was the Infernal Brigade (9th Hussars, 7th and 20th Chasseurs) commanded by General

Colbert. Two other brigades worth mention are Col. Soult's Brigade (8th Hussars, 16th and Chasseurs) and Gen. Pajol's Brigade (5th and 7th Hussars,

3rd Chasseurs).

The dragoons and the chasseurs were the most numerous French cavalry.

The horse chasseurs [chasseurs-a-cheval] were light cavalry and were often brigaded with the

hussars. The most famous was the Infernal Brigade (9th Hussars, 7th and 20th Chasseurs) commanded by General

Colbert. Two other brigades worth mention are Col. Soult's Brigade (8th Hussars, 16th and Chasseurs) and Gen. Pajol's Brigade (5th and 7th Hussars,

3rd Chasseurs).

There were several reasons why the Emperor formed so many regiments of chasseurs.

Their uniforms were cheaper than hussars' outfits and their horses were cheaper than

cuirassiers' mounts. The chasseurs were also capable of dismounted action, like the dragoons.

There were several reasons why the Emperor formed so many regiments of chasseurs.

Their uniforms were cheaper than hussars' outfits and their horses were cheaper than

cuirassiers' mounts. The chasseurs were also capable of dismounted action, like the dragoons.

The chasseurs however were best suited to reconnaissance duties and small warfare.

On 8th February 1814 a half squadron of 31st Chasseur captured 150 Austrian infantry near

Massimbona.

Another squadron captured 300 infantry between Marengo and Roverbella.

Even the scouts of the regiment did something to be proud of, they captured an Austrian

baggage column, which was moving into Villafranca with its escort. (Nafziger and Gioannini -

"The Defense of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Northern Italy, 1813-1814" pp 160-162)

The chasseurs however were best suited to reconnaissance duties and small warfare.

On 8th February 1814 a half squadron of 31st Chasseur captured 150 Austrian infantry near

Massimbona.

Another squadron captured 300 infantry between Marengo and Roverbella.

Even the scouts of the regiment did something to be proud of, they captured an Austrian

baggage column, which was moving into Villafranca with its escort. (Nafziger and Gioannini -

"The Defense of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Northern Italy, 1813-1814" pp 160-162)

Picture: French light cavalry sabre and scabbard (1802).

Photo from Military Heritage

Picture: French light cavalry sabre and scabbard (1802).

Photo from Military Heritage  Picture: French cavalry carbine from Military Heritage

Picture: French cavalry carbine from Military Heritage

LEFT: during campaign and in battle the Guard chasseurs wore dark green trousers,

strengthened with black leather on the inside and around the bottoms.

The trousers were closed on the outside by 18 buttons sewn on scarlet bands.

LEFT: during campaign and in battle the Guard chasseurs wore dark green trousers,

strengthened with black leather on the inside and around the bottoms.

The trousers were closed on the outside by 18 buttons sewn on scarlet bands.

One of the most known chasseurs was Montbrun. Louis-Pierre Montbrun (1770-1812) joined the

cavalry in 1789 in the age of 19. According to Terry J. Senior of napoleon-series.org

"This soldier was a superb equestrian, with a brilliant sword arm, and a terrific combat

record. He possessed an exceptional talent for controlling large formations of mixed cavalry.

Rated ahead of LaSalle on the basis that he was less headstrong and more calculating than the

legendary hussar commander."

One of the most known chasseurs was Montbrun. Louis-Pierre Montbrun (1770-1812) joined the

cavalry in 1789 in the age of 19. According to Terry J. Senior of napoleon-series.org

"This soldier was a superb equestrian, with a brilliant sword arm, and a terrific combat

record. He possessed an exceptional talent for controlling large formations of mixed cavalry.

Rated ahead of LaSalle on the basis that he was less headstrong and more calculating than the

legendary hussar commander."

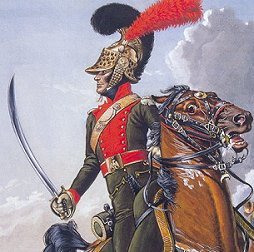

The hussar-mania contaminated France after sweeping over Europe.

The dash of attire and behaviour of Hungarian hussars displayed on the battlefields in the service of Austria

certainly made the best impression, and in due time the French army started changing her cavalry regiments

into hussars, in dress and in title. Lynn writes: "The last type of horsemen to join the ranks of the French cavalry were hussars,

a form of mounted unit composed of Hungarian light cavalry who forged their methods

of combat fighting against the Turks. Hussars were true light cavalry, used best

for raiding and scouting. ...

The first genuine French hussar regiment was raised in 1692 from Imperial deserters, and by 1710, the French

counted 3 regiments of these often outlandish cavalry, regarded by some more as thieves on horseback than as true

cavalrymen." (Lynn - "Giant of the Grand Siecle" p 492)

The hussar-mania contaminated France after sweeping over Europe.

The dash of attire and behaviour of Hungarian hussars displayed on the battlefields in the service of Austria

certainly made the best impression, and in due time the French army started changing her cavalry regiments

into hussars, in dress and in title. Lynn writes: "The last type of horsemen to join the ranks of the French cavalry were hussars,

a form of mounted unit composed of Hungarian light cavalry who forged their methods

of combat fighting against the Turks. Hussars were true light cavalry, used best

for raiding and scouting. ...

The first genuine French hussar regiment was raised in 1692 from Imperial deserters, and by 1710, the French

counted 3 regiments of these often outlandish cavalry, regarded by some more as thieves on horseback than as true

cavalrymen." (Lynn - "Giant of the Grand Siecle" p 492)

Photo: Hussar of Lasalle's "Hellish Brigade."

Reenactor group

Photo: Hussar of Lasalle's "Hellish Brigade."

Reenactor group

Guindey was quartermaster of the blue-clad 10th Hussars. He became fomous for killing Prussian Prince Louis Ferdinand at Saalfeld.

As a prominent leader of the Prussian court war-party, his death was grievously felt.

King of Prussia told his generals afterward: "You said that the French cavalry was worthless, look what their light

cavalry has done to us! Imagine what their cuirassiers will do!"

Guindey was awarded and transfered to the Horse Gerenadiers of the Imperial Guard.

Guindey was quartermaster of the blue-clad 10th Hussars. He became fomous for killing Prussian Prince Louis Ferdinand at Saalfeld.

As a prominent leader of the Prussian court war-party, his death was grievously felt.

King of Prussia told his generals afterward: "You said that the French cavalry was worthless, look what their light

cavalry has done to us! Imagine what their cuirassiers will do!"

Guindey was awarded and transfered to the Horse Gerenadiers of the Imperial Guard.

The 5th and 7th Hussars formed Lasalle's legendary Hellish Brigade

with Colonels Francois-Xavier Schwarz and Ferdinand-Daniel Marx as regimental commanders.

In 1806 After the victorious battles of Jena and Auerstädt, Lasalle participated in the pursuit of the Prussians.

His two regiments, total of 600-900 men, bluffed the great Prussian fortress of

Stettin with 180 guns and a garrison of 5,000 men.

into surrender !

The 5th and 7th Hussars formed Lasalle's legendary Hellish Brigade

with Colonels Francois-Xavier Schwarz and Ferdinand-Daniel Marx as regimental commanders.

In 1806 After the victorious battles of Jena and Auerstädt, Lasalle participated in the pursuit of the Prussians.

His two regiments, total of 600-900 men, bluffed the great Prussian fortress of

Stettin with 180 guns and a garrison of 5,000 men.

into surrender !  Picture: two French hussars and a girl. Picture by S.Letin.

Picture: two French hussars and a girl. Picture by S.Letin. The most famous hussar commander was General Antoine-Charles Lasalle,

"the man for high adventure and reckless deeds.

The most famous hussar commander was General Antoine-Charles Lasalle,

"the man for high adventure and reckless deeds.

Picture: Hussar. "Napoleon's Cavalry

Recreated in Color Photographs" by Maughan

Picture: Hussar. "Napoleon's Cavalry

Recreated in Color Photographs" by Maughan