TABLE OF CONTENTS:

TABLE OF CONTENTS:1. Introduction.

2. Cossacks Campaigning in Western Europe.

3. Cossacks' Tactics and Battles.

4. Organization.

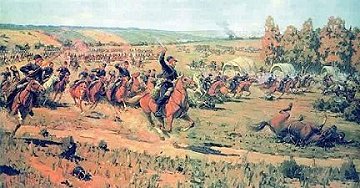

Picture: Cossacks in early spring 1813, by Wojciech Kossak. On the ground are corpses of French soldiers and horses.

.

Introduction: History, Weapons, Deployment.

The name Cossack is derived from the Turkic word quzzaq and mean simply "adventurer" and "freeman". This name has been shared by several groups throughout the history of Europe and Asia. The most prominent and numerous are the Russian Cossacks of the Don, Ural and Siberia regions. Also famous were the Ukrainian Cossacks who lived on the southern steppes of modern Ukraine. They grew astronomically during the 15th-17th centuries due to numerous runway peasants from Russia and Poland respectively. Cossacks paid no taxes and enjoyed a large measure of autonomy in the management of their communal affairs. Janet Hartley writes: "Cossacks are not a separate ethnic group (although they were designated as such in the Soviet period); they comprise mainly Russian and Ukrainian peasants and fugitives who had fled to the southern borderlands. They nevertheless regarded themselves as a separate group within the Russian empire, with separate institutional and social structure, who owed a loyalty to their Cossack host as well ass to the Russian tsar. The 18th and the early 19th century saw the transformation of CCossack communities from active resistors to central tsarist authority to loyal servitors of the state, but this did not mean that they had lost their sense of separate identity or thheir distrust of Russian officials and grandees." (Charles Esdaile - "Popular Resistance in the French Wars" p186) Cossacks played a key role in the expansion of the Russian Empire into Siberia, the Caucasus and Asia. They also served as guides to most Russian expeditions formed by civil geographers, traders, explorers and surveyors. In 1648 the Russian Cossack Simeon Dezhnev opened a passage between America and Asia. (ext.link) During the Napoleonic Wars the Cossacks participated in numerous campaigns and battles. In late 1790s they went with Suvorov to Italy and Switzerland. In 1805 they took part in the disastrous Austerlitz Campaign. In 1806 and 1807 the Cossacks were in Eastern Prussia in Bennigsen's army. There were several Cossack regiments fighting against the Swedes and Turks in 1808, 1809 and 1810. In 1812 and 1813 the Cossacks covered themselves with glory. The relentless pursuit by the light cavalry and Cossacks, the winter and the tsar's and people's determination resulted in a truly disastrous defeat on Napoleon. The Grand Army ceased to be grand, it even ceased to be an army. Fewer than 100,000 of the 500 000 that Napoleon had used for the invasion returned west.

The Cossacks were again in Paris in 1815. A large group of Cossacks was despatched to find the Prussians and English armies advancing on Paris and they were the first Allies' troops who marched through Paris very shortly after Waterloo.

Nikolai Vasilievich Illovaiski ( 1772 - 1828 ) was another talented Cossack commander. Nikolai Mozhak writes: "He was enlisted to the military service in the age of 6 as a private cossack. In the age of 8 he took part in his first military expedition to the Crimea for suppressing the Crimea Tatars that supported Turks." Illovaiski participated in campaigns against the Turks, Poles and the French. In 1813 after the Battle of Bautzen he left the army, his health was failing, and went back to the Don.

Deployment of Cossacks.

In 1811 the assignment of Cossack regiments was as follow: - - - - - - - - - - - - Lifeguard Regiment (542 + 43 noncombatants) guard unit for the Tzar, counted as regular cavalry - - - - - - - - - - - - Ataman Regiment (877 + 2 noncomb., in 5 sotnia) guard unit for the Ataman of the Don Cossacks - - - - - - - - - - - - 60 regiments (590 + 1 noncombatant each. In the field however, they averaged 360-450 men.) - - - - - - - - - - - - In 1812 further 26 regiments were raised. The 86 regiments were assigned as follow: - - - - - - - - - - - - 64 were stationed along the western broder, 10 stationed in Caucasus, 8 in Georgia, 2 in Crimea, - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 in Moldavia, and 1 in Finland - - - - - - - - - - - - Lifeguard Black Sea Sotnia - a guard unit for the Tzar, counted as regular cavalry - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 regiments (5 sotnia each) on the Kuban River, in 1813 1 regiment fought with the napol. troops - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 druzhina (5 sotnia each) - Cossacks on foot and 9 of them were stationed in Caucasus - - - - - - - - - - - - Lifeguard Sotnia (125 + 6 noncomb.) a guard unit for the Tzar, counted as regular cav. - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 regiments (3 faced the napoleonic troops, and 7 stationed in Ural facing the Kirgiz) - - - - - - - - - - - - Ataman Regiment (5 sotnia) - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 regiments (5 sotnia each) - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 town commands (total of approx. 1000 foot Cossacks) - - - - - - - - - - - - 2 horse batteries - - - - - - - - - - - - Orenburg Ataman Regiment (1177 + 1 noncombatant in 10 sotnia) - - - - - - - - - - - - 3 regiments (5 sotnia each), they were moved against the napoleonic troops. - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 detachments (500 mounted and 500 foot soldiers each) in Orenburg frontier facing the Kirgiz - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 border settlement detachments (total 800 horsemen) - - - - - - - - - - - - 12 trans-Baikal border settlement detachments (total 900 horsemen) - - - - - - - - - - - - 8 town commands incl. Kamchatka and Yakutzk (total 1850 horsemen)

The officers were armed with sabers, but they have never mastered this weapon. "... in 1812 ... a Prussian uhlan major fought a man-to-man duel with a Cossack officer (armed with saber) between their two regiments and captured him ..." ( - John Elting) Prokesch writes: "... the lance is their main weapon. He knows how to use this weapon with great skill and security, nevertheless the fact that it is one and a half foot longer as the Polish lance. He knows how to use his sabre just as well; officers and NCO’s practice them for use against the Turks. The pistol is of less value to him. He considers it not really as a weapon, but only as a tool to scare the enemy. He fires only to fire, not to hit anything, and in common there are few Cossacks which use their pistols... Tettenborn armed his Cossacks completely with French muskets... The Cossack loves the use of a firearm, because of the reason that he fears the one of the enemy. He wants to take artillery with him, and the name Poushki (cannon) is for him a word of joy, as well as of fear...A tenth of every squadron consists of marksmen; Strelki. Rifle and pistols are mostly Turkish or Persian booty." (Prokesch - "Ueber den Kosaken, und dessen Brauchbarkeit im Felde")

|

Cossacks Campaigning in Western Europe The Cossacks, according to August von Haxthausen ("Studies on the interior of Russia" 1843), were "The liveliest and boldest of all the Russians ..." The horsemanship of Cossacks was second to none in Europe. They could pick up a small coin from the ground during full gallop or fire from pistols from under horse's belly. The Cossacks, portrayed by some as Satan’s bastard offspring, were constant menace for the Frenchmen, Germans, Poles and Italians. Cossacks' horses were not large and they appeared as if they should crumble under the sheer weight of their diverse loads. The bearded warriors "with six looted watches in each pocket" frightened the westerners. There were cases in Italy and Germany when townspeaople came out to greet them as liberators, only to be quickly despoiled of clothes, watches and all cash. The naked men and women fled in horror. Sir Wilson campaigned with the Russians in 1813 in Germany and wrote: "The country through which we are passing is in great distress. The Cossacks have devoured or destroyed the little that the stagnation of commerce had enabled the inhabitants to provide. ... In many parts of Germany it is said that the cossack terror is so great that prayers are put up: "De Cossaquibus, Domine, libere nos !" In other churches they have added the term Cossack to the original Devil as more expressive of his mischievous proceedings. It is a great pity that they should be so lawless, for they counterbalance the service which they render." Reverend Schlosser, vicar of Gross-Zschocher writes: "A swarm of about 20 to 30 Cossacks had broken into my house the day before, each with an empty bottle which they wanted to have filled with brandy. As we could only give them a little each they became angry, grabbed me, pushed me up against the wall and threathened me with pistols and sabres, shouting furiously. My good wife fell about the dirty neck of the most furious one and my little daughter clung about her knees and wept loudly, crying for mercy. But I would have been done for had not an Austrian NCO come in just in time. He saved my life by explaining the situation to the Cossacks and protecting me." (Digby-Smith - "1813: Leipzig" p 137)

In 1802 in the Black Sea area were formed 10 regiments (and 10 foot cossack regiments); each of 5 sotnias. In 1811 from the Kalmucks living in Astrakhan, Saratov, and Caucasus provinces and in the Don area were formed: 1st and 2nd Kalmuck Regiment, 1st and 2nd Stavropol Kalmuck Regiment, and 1st and 2nd Bashkir Regiment. Each regiment had 5 sotnias. The Kalmucks and Tartars were also accepted into the regiments of the Don Cossacks. In their ranks served approx. 8% Kalmucks and 1 % Tatars. According to Richard Riehn, in 1812 there were 4 Tatar, 2 Kalmuk, 1 Chechen, and 2 Bashkir regiments. Later were formed 2 Kalmuk and 18 Bashkir regiments.

For the Cossacks he was through and through soldier. Simple manners, brave and so successful. The Cossacks pondered at his combative character and thought that he must have had Cossack grandparents ! Marinated in perfumes and flamboyantly dressed, he led the cavalry in such a way that the Cossacks wished to have him as their king. On several occassions they surrounded him expressing their admiration ... and received money and watches.

|

Cossacks' Tactics and Battles.

Although the Cossacks were one of the finest light cavalry in the world,

they war from perfection.

In 1799 in Italy, "The allied chief of staff Major-General Chasteler was the single person

who was willing to take proper account of the Cossacks' limitations and potentials.

Denisov had to explain to him that the

(Duffy - "Eagles over the Alps" pp 30-31)

Cossacks in small warfare.

The napoleonic cavalry struggled in the small warfare against the Cossacks, including the elite unit of light cavalry, the 2nd Lancer Regiment of the Guard [Red Lancers]. Austin writes: "Approaching stealthily, Cossacks nevertheless (again) carry off the Dutch regiment's outpost picket. And again 'only one man escaped flat out at a gallop and brought the news to our camp. Even an hour and a half's pursuit couldn't catch up with the Cossacks.' Mortified by this second surprise of the campaign, Colbert doubles the 2nd Regiment's outposts; and, to make assurance doubly sure, mingles the Dutchmen with the warier, more experienced Poles." (Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 333)

Chlapowski of Old Guard Lancers describes how they fought with the Cossacks: "News reached the headquarters at Dabrowna that a Russian force had crossed the Dnieper River ... The Emperor sent four squadrons of Polish Guards under Kozietulski to investigate. We set off after midnight, and ... arrived at a spot half mile from Katane. There we encountered our first Cossacks. Our main body halted by som ebuilding and one squadron went out to meet them. The Cossacks retreated off to our left, towards the Dnieper. At about this time the sun rose and we were able to see the country round about. To our front stood a line of cavalry on the crest of a hill, screened by a few hundred Cossacks. Kozietulski now recalled the first platoon, which had already come to grips with the Cossacks, and he formed the leading squadron into line.

The regular cavalr must have been able to see our other three squadrons in support, as they did not move from their position. But the Cossacks approached with increasing boldness, firing with their ancient pistols. As we sent nobody out to skirmish with them, they came closer and closer, shouting; 'Lachy !' (slang for Poles) when they discovered we were Polish. A Cossack officer on a fine grey horse came as close as a 100 paces, perhaps less, and in good Polish challenged us to meet him in single combat.

Kozietulski forbade any of us to move.

On 12th (24th) September there was a fight at Desna, on 17th (29th) September at Chirikovo, on 19th (Oct. 1st) September at Olshanki, on 23rd (Oct. 5th) September at Kobrin, on 26th (Oct. 8th) September at Shebrin and at Nikolske, on 4th (16th) October at Koziany, on 7th (19th) October at Slonim and at Ushachi, on 14th (26th) October at Vysokiye Steny, on 19th (31st) October at Kolotzki Monastyr, on 20th October (1st Nov.) at Gzhatzk and at Tsarevo-Zaimishche, on 3rd (15th) November at Koidanov, on 18th (30th) November at Zembin and at Pleshchinitza, on 25th November (7th Dec) at Smorgonie, on 12th (24th) December at Shavle and on 22nd (Jan. 3rd 1813) December action at Libava.

"Never get into a skirmish with Cossacks"

"Nearing Bouikhovo after nearly 3 hours' ride, Calkoen's squadron [of Red Lancers] were advancing a few hundred yards ahead of the Poles when Ltn. Doyen led his point troop up a hillock. They were immediately attacked from all sides by the Cossacks. Ltn. van Omphal's troops were at once sent to help them disengage, but were outflanked in their turn. The Red Lancers fell back towards the Polish squadron, who had halted and taken up battle formation. Under this cover the Dutch Lancers regrouped and charged the Cossacks again ..." (Ronald Pawly - "The Red Lancers") In 1812 at Famonskoie the Cossacks ambushed and captured a whole detachment of the Red Lancers. General Colbert mounted his horse and set off with 2 squadrons in pursuit, but the Cossacks made off with their prisoners so quickly that all that could be seen were their hoof prints in the mud. At Smolensk Chlapowski had another encounter with the Cossacks: "From the Emperor's tent we could see all of Smolensk ... There were masses of Cossacks circling in front of the city. Between the French line and the city walls was a massive gully into which the Cossacks had spilled. As I was on duty that day, I was ordered by the Emperor to take a squadron and force the Cossacks wiwthdrew. Coming up out of the ditch on the far side, I deployed the squadron in a single line, as I expected the enemy to shoot at us from the walls. Sure enough, they fired a number of howitzer shells, one of which exploded in the middle of the squadron. A few men were wounded, and some horses broke ranks in fright, so the Cossacks seized the moment to charge us. They were upon us very quickly, and I had to parry one of their lances with my saber. I damaged the lance but did not cut right through it, and it struck my horse's head, wounding it from its ears to the nostrils. Captain Skarzynski accounted for 2 or 3 Cossacks. Cossack lances are longer than ours, and in a close fight they handled less well. Our squadron repulsed this attack and sent the Cossacks back to the shelter of their walls."

Lifeguard Cossacks in pitched battle.

Marbot explained why this happened: "This treatment resulted in the enemy centre yielding and it was about to give way when the Tzar of Russia who had witnessed the disaster, rapidly advanced the numerous cavalry of his Guard which, encountering the squadrons of Latour-Maubourg in the state of confusion which always follows an all-out charge, repelled them in their turn and took back 24 of the guns which they had just captured." Tsar Alexander seeing the charge of the Lifeguard Cossacks, exlaimed: "They are going into fight as if they were coming to a wedding."

Cossacks vs Regular Troops.

In 1812 at Ostrovno the French 16th Chasseur Regiment was attacked by Cossacks. The chasseurs delivered a volley at close range (30 paces) The Cossacks however closed with them and drove them back in disorder. Some Frenchmen fled into the ravine and some behind the squares of 53rd Line Infantry Regiment. The Old Guard cavalry however had no fear of the Cossacks. When one of the Polish lancers lost his headwear, Officer Jerzmanowski ordered him to go back and retrieve it to prevent the enemy from claiming any trophy taken from this regiment. It was unusual since many troops panicked before Cossacks and left behind their wounded, weapons, not to mention headwears ! "During Blücher’s retreat from Meaux to Soissons in March 1814, Colonel Nostitz attacked with 40 Cossacks a whole squadron of Vélites of the Guard on open terrain near the Bridge of Wailly. The Cossacks withstood the fire of the vélites, and then threw themselves upon them, and the whole squadron was defeated." (Prokesh - "Ueber den Kosaken ...") In August 1812 Chernishev with 5 Cossack regiments and 4 guns attacked the village of Weddin defended by squadron of 4th (Polish) Uhlan regiment, three (Polish) companies of infantry and 2 guns. The defenders were under Colonel Kostanecki. The ensuing battle raged for 11 hours (!) and Cossacks made 10 attempts to capture the village. Approx. 500 Cossacks dismounted to combat as skirmishers, but to no avail. (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 121)

In 1812 at Mir the Cossacks scored another victory over Polish cavalry.

Platov with eight Cossack regiments and two Don batteries deployed in the woods south of Mir.

One Cossack regiment (Sisoiev-III's) was posted on the southern edge of the village. In front of Mir stood Platov's advance posts.

One brigade of the French [Polish] 4th Light Cavalry Division advanced on Mir with the 3rd Uhlans leading the way. Behind the 3rd were the 15th and 16th Uhlan Regiment. The 3rd Uhlans threw back Platov's advance posts and traversed the village at a gallop. The 3rd Uhlans attacked Sisoiev-III's Cossack Regiment but Platov's counterattacked with the bulk of his force. The Cossacks had struck Poles' front, flanks and rear nearly annihilating the 3rd Uhlans.

General Turno brought up the 15th and 16th Uhlans and held Platov for a while before being thrown back.

In 1812 at Drouia Kulniev's force (hussars and Cossacks) crossed the bridge and began to deploy before the village. Nafziger writes: "The Cossacks continued to hold the French cavalry until four squadrons of the Grodno Hussars arrived. The hussars immediately attacked the French and pushed them back to a ravine by Litichki. Here the French reformed their cavalry into four columns. Ridiger, seeing the remaining four squadrons of his regiment closing in, moved on the French flanks and threw them in great disorder to the village Jaga. The French reformed their cavalry there. ... part of the chasseurs dismounted and formed a skirmish line. The Russian hussars charged again while the Cossacks attacked the French in the flank. The French fell back with the Russians in pursuit until they reached Tschernevo." (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons" pp 114-115)

|

Organization of the Cossacks: Regiments and Brigades.

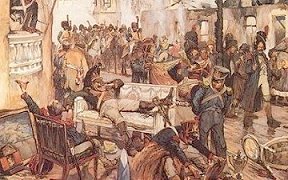

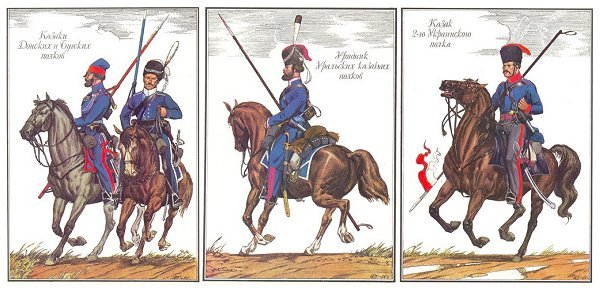

Picture by Oleg Parkhaiev Russia.

Cossack regiment had a simple organization. It had colonel, called polkovnik (from Polish pulkovnik), small staff, and 5 sotnia. On paper the strength of single regiment was more than 500 men. In the field hovewer there were only 300-450 men in the ranks.

Regiment and sotnias

The regiments of Don Cossacks were named after their commanders. The Ukrainian and other

Cosscaks were numbered and named according to their nationality or district.

The NCO was the real soul of the Cossack regiment. He owed his position from his service and his fame. If he became commander of a detachment then he changed quickly in a tyrant for his subordinates; and he used his position to accumulate trophies and loot.

Each Don and Bug Cossacks regiment carried 5 flags in various colors painted with religious

pictures or martial emblems. Sisoiev-III's Regiment carried in addition a St.George flag.

If a regiment returned to its homelands without its colour, it was dishonoured.

The flags for the regiments of the Ural Cossacks were not recorded.

Staff: 1 polkovnik (colonel) and 1 putzer (colonel's servant) 1 podpolkovnik (colonel-lieutenant) - his was present in less than half of all Don regiments 1 voiskovoi starshina 1 quartermaster - in the rank of sotnik (first lieutenant) 1 polkovyi pisar also called kaznachei (regimental clerk, cashier) 2 pisar (clerks in the rank of NCO) 1 judge

I Sotnia

II Sotnia

III Sotnia

IV Sotnia

V Sotnia

Two or three regiments (sometimes more) formed brigades. Cossack brigades were attached to regular troops. There were also two or three independent corps. The Cossacks were rarely formed in divisions.

Below is organization of Cossacks on 10th August 1813 in Saxony.

In that specific time period there were no 'divisions' of Cossacks.

Several regiments were assigned as escort to army headquarters.

Several brigades were attached to cavalry corps. These Cossacks made life easier for the uhlans and hussars, as they did the scouting and patroling.

Transporting prisoners: 2 Bashkir regiments COSSACK CORPS - Ataman Platov - - - - Brigade - GM Kudashov: 3 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - Col. Bergman: 4 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - GM Shcherbatov: 4 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - : 1 Cossack regiment, and Don Cossack Battery COSSACK CORPS - GM Chernyshev - - - - Brigade - Ltn.-Col. Lapuhin: 3 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - Illovaiski-IX: 3 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - Colonel Melnikov-V: 2 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - Colonel Benkendorf: 3 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - GM Narishkin: 2 Cossack regiments Cossacks in Vasilchikov's Cavalry Corps - - - - 'Brigade' - GM Karpov-II: 9 Cossack and 1 Kalmuck regiments Cossacks in Korff's Cavalry Corps - - - - Brigade - GM de Witte: 3 Cossack regiments - - - - Attached units: 5 Cossack regiments Cossacks in Pahlen's Cavalry Corps - - - - Brigade - : 4 Cossack regiments Cossacks in Laptiev's XII Infantry Corps - - - - Brigade - GM Stahl-I: 5 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - GM Prendel: 2 Cossack regiments - - - - Brigade - : Opolchenie

Picture: uniforms of the famous red-clad Lifeguard Cossacks. Picture by P. Courcelle, France.

|

|

the Bolsheviks during the Russian Red Revolution in the early 20th century. "Cossack cultures were largely suppressed during the time of the Soviet Union but are now in the process of revival." (wikipedia.org) |

Sources and Links

Recommended Reading.

Charles Esdaile - "Popular Resistance in the French Wars" (2005)

Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" translated by Tim Simmons

Lachoque - "The Anatomy of Glory"

The Cossacks: Origins, Culture, Organization, History

Ukrainian Cossacks

Wargame: Cossacks Heaven

The Old Cossacks

The sensational Russian Cossack State Dance Company

Flags from warflag.com

Photo from Borodino reenactment, by korfilm

Dr. Freiherr von Baumgartner - "Vollständiges Verzeichnis aller Kosaken-Formationen 1812" publ. 1943

(transl. by Mark Conrad)

Russian Infantry - - - - - Russian Cavalry and Cossacks - - - - - Russian Artillery

Battle of Heilsberg 1807

Bennigsen vs Napoleon

Battle of Borodino 1812

The bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic wars

Battle of Dresden, 1813

Russians, Austrians and Prussians

crushed by Napoleon

Battle of Leipzig, 1813

The Battle of the Nations,

the largest conflict until World War One.

Battle of La Rothiere 1814

Russians under Blucher defeated Napoleon.

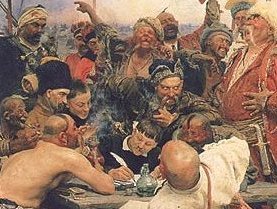

Picture: Cossacks writing incredibly insulting reply to Turkish Sultan's demand for surrender (1675). They laugh their socks off over each word. Picture by Repin.

Picture: Cossacks writing incredibly insulting reply to Turkish Sultan's demand for surrender (1675). They laugh their socks off over each word. Picture by Repin. In 1814 the dreaded Cossacks entered Paris. They were received with the best foods but they preferred to cook their own meals. The beautiful houses, palaces and courts, and the products of luxury which they encountered in Paris did not tempt them. In the beginning the Parisians were scared of the the unique troops. Russian and Cossack officers gathered in certain restaurannts and hammered on the tables yelling bistro ! which is Russian word for "quickly". Hence the name bistro for this type of restaurant.

In 1814 the dreaded Cossacks entered Paris. They were received with the best foods but they preferred to cook their own meals. The beautiful houses, palaces and courts, and the products of luxury which they encountered in Paris did not tempt them. In the beginning the Parisians were scared of the the unique troops. Russian and Cossack officers gathered in certain restaurannts and hammered on the tables yelling bistro ! which is Russian word for "quickly". Hence the name bistro for this type of restaurant.

The most famous Cossack commander was Platov.

Ataman Matvei Platov (1757-1818) was a seasoned commander, already in 1774 he fought

against the Crimean Tatars.

Upon Alexander I's ascension to the throne, he was appointed Ataman (Headman) of the

Don Cossacks. In 1805, Platov ordered the Cossack capital to be moved from Starocherkassk

to a new location, known as Novocherkassk. He distinguished himself in 1806-7, 1812 and 1813

against the French. Platov scourged the French during their retreat from Moscow in 1812,

and again after their defeat at Leipzig. During his visit in England he was enthusiastically

greeted by the Londoners. Platov was awarded a golden sword and a honorary degree by the

The most famous Cossack commander was Platov.

Ataman Matvei Platov (1757-1818) was a seasoned commander, already in 1774 he fought

against the Crimean Tatars.

Upon Alexander I's ascension to the throne, he was appointed Ataman (Headman) of the

Don Cossacks. In 1805, Platov ordered the Cossack capital to be moved from Starocherkassk

to a new location, known as Novocherkassk. He distinguished himself in 1806-7, 1812 and 1813

against the French. Platov scourged the French during their retreat from Moscow in 1812,

and again after their defeat at Leipzig. During his visit in England he was enthusiastically

greeted by the Londoners. Platov was awarded a golden sword and a honorary degree by the

General-Major Alexandr Ivanovich Chernyshev (1785-1857) was a famous Cossack raider.

In 1812 Chernyshev was promoted to general-major, and in 1814 to general-lieutenant.

Chernyshev was not well-known in Europe but in Russia in that time he was very popular.

In 1812 Chernyshev's aggressive pursuit and hit and run tactics demoralised the French.

In 1813 and 1814 his raids deep into enemy territory were quite spectacular.

Chernyshev's Cossacks raided Kassel, the capital of Westphaly. After being driven out of

Kassel,

General-Major Alexandr Ivanovich Chernyshev (1785-1857) was a famous Cossack raider.

In 1812 Chernyshev was promoted to general-major, and in 1814 to general-lieutenant.

Chernyshev was not well-known in Europe but in Russia in that time he was very popular.

In 1812 Chernyshev's aggressive pursuit and hit and run tactics demoralised the French.

In 1813 and 1814 his raids deep into enemy territory were quite spectacular.

Chernyshev's Cossacks raided Kassel, the capital of Westphaly. After being driven out of

Kassel,  All rank-and-file Cossacks of the Napoleonic Wars carried 8-foot long lance with

a steel spearhead surmounting a steel ball to secure easy withdrawal of the point.

Some Cossacks were also armed with curved sabers and 1-8 (!) pistols. Some

carried carbines or muskets or other firearms. Each sotnia (squadron) had muskets for 11 Cossacks trained as marksmen.

All rank-and-file Cossacks of the Napoleonic Wars carried 8-foot long lance with

a steel spearhead surmounting a steel ball to secure easy withdrawal of the point.

Some Cossacks were also armed with curved sabers and 1-8 (!) pistols. Some

carried carbines or muskets or other firearms. Each sotnia (squadron) had muskets for 11 Cossacks trained as marksmen.

The idea of being captured by the Cossacks was a nightmare for the western troops.

One of Napoleonic officers described what happened when he was taken prisoner in 1806-7 campaign. "One [dragoon squadron] charged right into and through us. I fell between two horses, struck in the throat. I lost consciousness, and don't know how long I lay there, nor did I know who stripped my uniform off me. When I came to, I was lying on the ground surrounded by a group of Cossacks. .... A Cossack officer ordered me to stand, but I could not raise myself as my neck and shoulder were stiff. He gave me his hand and helped me up, ordered one of his Cossacks to dismount and put me on his horse. ... I sat with my teeth rattling from the cold, as I was undressed. A Cossack colonel rode up ... and gave me a nip of vodka. ... My headwear had gone missing ... We joined some other prisoners who had already been brought in ... We were led to some kind of a stone building in the city [Danzig, Gdansk] and after 2 days to Farwasser where we were put up on a Swedish ship ... " (Chlapowski/Simmons - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p 27)

The idea of being captured by the Cossacks was a nightmare for the western troops.

One of Napoleonic officers described what happened when he was taken prisoner in 1806-7 campaign. "One [dragoon squadron] charged right into and through us. I fell between two horses, struck in the throat. I lost consciousness, and don't know how long I lay there, nor did I know who stripped my uniform off me. When I came to, I was lying on the ground surrounded by a group of Cossacks. .... A Cossack officer ordered me to stand, but I could not raise myself as my neck and shoulder were stiff. He gave me his hand and helped me up, ordered one of his Cossacks to dismount and put me on his horse. ... I sat with my teeth rattling from the cold, as I was undressed. A Cossack colonel rode up ... and gave me a nip of vodka. ... My headwear had gone missing ... We joined some other prisoners who had already been brought in ... We were led to some kind of a stone building in the city [Danzig, Gdansk] and after 2 days to Farwasser where we were put up on a Swedish ship ... " (Chlapowski/Simmons - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p 27)

In 1813 at the Battle of Kulm the Cossacks captured French generals Haxo and Vandamme.

Dominique-Joseph Vandamme was captured when while in the middle of a column of retreating

French infantry a small band of Cossacks rode up seized him and his aide

General Haxo and rode off before the surprised infantry could open fire.

In 1813 at the Battle of Kulm the Cossacks captured French generals Haxo and Vandamme.

Dominique-Joseph Vandamme was captured when while in the middle of a column of retreating

French infantry a small band of Cossacks rode up seized him and his aide

General Haxo and rode off before the surprised infantry could open fire.

The Bashkirs, Tartars and Kalmuks were even worse than Cossacks.

The Cossacks kept their eye on the Kalmuks and Bashkirs

to prevent any unchaperoned "field trips" into town. There were reported cases of women raped on horseback and other artocities committed by the Asian warriors.

The Bashkirs, Tartars and Kalmuks were even worse than Cossacks.

The Cossacks kept their eye on the Kalmuks and Bashkirs

to prevent any unchaperoned "field trips" into town. There were reported cases of women raped on horseback and other artocities committed by the Asian warriors.

According to Austrian officer A. Prokesch "A characteristic which makes the Cossacks

especially useful for the ‘light war’, is their total indifference for a thousand things,

which are called ‘obstacles’ in the military sense ... During the attack on Holland the

adroitness with which six Cossack regiments under Narischkin and Stael operated between

hundreds of waterways and many fortified places astonished all experienced military buffs....

According to Austrian officer A. Prokesch "A characteristic which makes the Cossacks

especially useful for the ‘light war’, is their total indifference for a thousand things,

which are called ‘obstacles’ in the military sense ... During the attack on Holland the

adroitness with which six Cossack regiments under Narischkin and Stael operated between

hundreds of waterways and many fortified places astonished all experienced military buffs....

Britten-Austin described Cossacks' tactics in 1812.

Britten-Austin described Cossacks' tactics in 1812.  Napoleon believed that the capture and destruction of Moscow (see picture) had

strengthened his own bargaining power and sent two messengers to Alexandr, asking

for an end to hostilities. The tsar disappointed the French and refused to enter

any talks.

By this time Napoleon's communication lines became overextended and the Cossacks

and hussars began their brilliant campaign of attacking enemy's transports, magazines,

and convoys. During the dark and cheerless days the enemy was slowly retreating, burdened

by loot and only the cries "Cossacks!" kicked them into activity.

Napoleon believed that the capture and destruction of Moscow (see picture) had

strengthened his own bargaining power and sent two messengers to Alexandr, asking

for an end to hostilities. The tsar disappointed the French and refused to enter

any talks.

By this time Napoleon's communication lines became overextended and the Cossacks

and hussars began their brilliant campaign of attacking enemy's transports, magazines,

and convoys. During the dark and cheerless days the enemy was slowly retreating, burdened

by loot and only the cries "Cossacks!" kicked them into activity.

In 1812 the Cossacks were evrywhere.

Henri Lachoque writes: "At Katyn the Poles had great difficulty getting rid of several hundred scouting in front of a mass of Russian cavalry. Lahy ! Lahy ! [Poles in old Russian slang] the Russians cried, firing off their carbines at some distance from the leading squadron to provoke the Guard Lancers. 'Never get into a skirmish with Cossacks' was the Poles' advice. However a formal charge sent them flying."

In 1812 the Cossacks were evrywhere.

Henri Lachoque writes: "At Katyn the Poles had great difficulty getting rid of several hundred scouting in front of a mass of Russian cavalry. Lahy ! Lahy ! [Poles in old Russian slang] the Russians cried, firing off their carbines at some distance from the leading squadron to provoke the Guard Lancers. 'Never get into a skirmish with Cossacks' was the Poles' advice. However a formal charge sent them flying."

The Lifeguard Cossack Regiment was the creme-de-la-creme of Cossacks.

They were men selected for their height and strength. Many came from regular cavalry.

The Lifeguard Cossack Regiment was the creme-de-la-creme of Cossacks.

They were men selected for their height and strength. Many came from regular cavalry.

One of the most known actions of Cossacks was their raid on Napoleon's flank at Borodino.

Platov's Cossacks moved without major problems, they crossed the Voina River ("War River") further north than Uvarov's cavalry, and made raid on French rear.

One of the most known actions of Cossacks was their raid on Napoleon's flank at Borodino.

Platov's Cossacks moved without major problems, they crossed the Voina River ("War River") further north than Uvarov's cavalry, and made raid on French rear.

Map: Combat at Romanov, 1812.

Map: Combat at Romanov, 1812.

Nafziger writes: "Turno was the reinforced by the arrival of ... 2nd, 7th and 11th Uhlans.

At the same time, Platov was reinforced by the arrival of GM Vasilchikov with the Ahtirka Hussars, the Kiev and New Russia Dragoons, the Lithuania Uhlans and the 5th Jagers.

However night fell as they arrived and the battle broke off. On the 10th, Platov drew up his rearguard (Ahtirka Hussars, Kiev and New Russia Dragoons, Illovaiski #5, # 10, # 11 and # 12, and two horse batteries) along the road to Mir, and placed the rest of the Cossacks in an attempt to ambush the Polish cavalry as it resumed the advance." Kouteinikov's force (half of the Ataman Cossacks, Grekhov-VIII's Cossacks, Haritonov's Cossacks and Simferopol Tartars) moved to Simiakovo.

Nafziger writes: "Turno was the reinforced by the arrival of ... 2nd, 7th and 11th Uhlans.

At the same time, Platov was reinforced by the arrival of GM Vasilchikov with the Ahtirka Hussars, the Kiev and New Russia Dragoons, the Lithuania Uhlans and the 5th Jagers.

However night fell as they arrived and the battle broke off. On the 10th, Platov drew up his rearguard (Ahtirka Hussars, Kiev and New Russia Dragoons, Illovaiski #5, # 10, # 11 and # 12, and two horse batteries) along the road to Mir, and placed the rest of the Cossacks in an attempt to ambush the Polish cavalry as it resumed the advance." Kouteinikov's force (half of the Ataman Cossacks, Grekhov-VIII's Cossacks, Haritonov's Cossacks and Simferopol Tartars) moved to Simiakovo.

In 1813 at Hagelberg Aleksandr Benkendorf (see picture) galloped with Cossack regiments in front of the whole French position, from the far right to the far left wing.

Musketry accompanied the Cossacks and they were received by grapeshot. Nevertheless,

a Cossack regiment (300-400 men) defeated squadron of cuirassiers and some light infantry, in full view of the artillery. Then they captured two cannons and several wagons which they took with them.

In 1813 at Hagelberg Aleksandr Benkendorf (see picture) galloped with Cossack regiments in front of the whole French position, from the far right to the far left wing.

Musketry accompanied the Cossacks and they were received by grapeshot. Nevertheless,

a Cossack regiment (300-400 men) defeated squadron of cuirassiers and some light infantry, in full view of the artillery. Then they captured two cannons and several wagons which they took with them.

Picture:

Picture: