.

It is a curious fact that by the mere force of circumstances

the Spanish Catholics were driven to an alliance with protestant England,

a power which the Spaniards were accustomed to look upon as

the incarnation of the most damnable heresy.

|

The British in Peninsula.

The campaign in Spain "was to the Napoleonic wars

what North Africa was to the WW2, an arena of British failure,

redeemed by victory only when the enemy broke one of the great

laws of war: NEVER INVADE RUSSIA."

- 'The Economist' Oct 3rd 2002, London

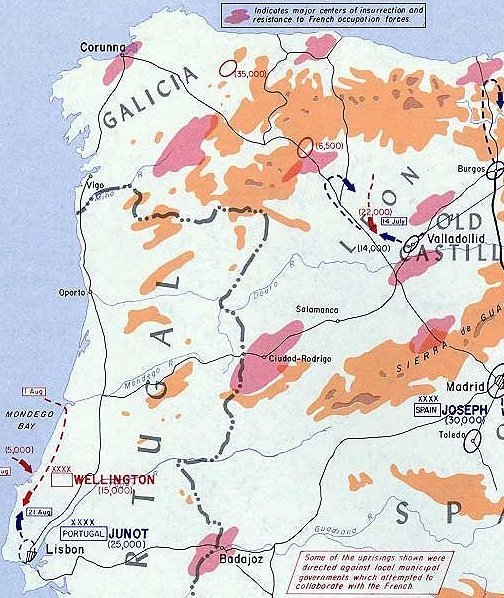

On picture: in 1812 the second in command of the British army,

Lord Paget, was captured by French dragoons. In 1809 the first in command, Wellington, was

almost captured at Combat of Casa de Salinas.

On picture: in 1812 the second in command of the British army,

Lord Paget, was captured by French dragoons. In 1809 the first in command, Wellington, was

almost captured at Combat of Casa de Salinas.

It is a curious fact that by the mere force of circumstances the

Spanish Catholics were driven to an alliance with protestant England, a power which the

Spaniards were accustomed to look upon as the incarnation of the most damnable heresy,

and little better than the Grand Turk himself became ally. Napier writes: "As early as

April, General Castanos, then commanding the camp of San Roque, had entered into communication

with Sir Hew Dalrymple, the Governor of Gibraltar. He was resolved to seize any opportunity

that offered to resist the French, and he appears to have been

the first Spaniard who united patriotism with prudent calculation - readily acknowldging the

authority of the Junta of Seville, and stiffling the workings of self-interest, with a virtue by no means common to his countrymen at that period."

(Napier - “History of the War in Peninsula 1807-1814” p 36)

Britain profited from the campaign of 1809 after Napoleon had been compelled to leave Spain

hurriedly to take command in Germany. Had he been able to remain on the Peninsula, it is

probable the campaign in Spain would have turned out very differently. The Emperor might well have broken Spanish resistance

and driven Wellington into the sea. (Rothenberg - "The Emperor's Last Victory" p 27)

Wellington's corps in Spain was viewed by Russia, Prussia and Austria as of little importance,

and the Allies generals saw no British troops in the main theater of war facing the

Emperor himself. The Allies asked Great Britain to send troops into central Europe, to fight the French,

but the Government refused.

According to some British authors, it was Wellington's army, and not the Spaniards,

was the primary cause of victory in Spain. Without the British, the guerillas would do more

harm to the Spanish people than to the enemy. Napier writes: "That the guerilla system could

never seriously affect the progress of the French, is proved by the fact, that the constant

aim of the principal chiefs was to introduce the customs of regular troops; and their success against the enemy was proportionate to their

progress in discipline and organization. There were not less than 50,000 of these irregular soldiers, at one time, in Spain;

and so severely did they press upon the country tha it may be assumed as a truth, that if the English army had abandoned the contest, one of the surest means

by which the French could have gained the good will of the nation would have been extirpating

of the partidas." (- Napier Vol II, p 128)

Royal Navy.

Without the Royal Navy, Britain's campaign in Peninsula

could never have been waged and certainly not with the success

that was eventually achieved.

According to David Gates without the Royal Navy, Great Britain's campaign in Spain and Portugal could never have been waged

and certainly not with the success that was eventually achieved.

He writes: "As well as ferrying troops to and from

the war zone, the fleet transported virtually all the gold, equipment, food and munitions used by the Allied armies

and guerillas. ... Moreover, whereas the lack of any naval support of their own confined the French

to moving via the appalling Peninsular roads, the Allied forces could frequently transport men and material by sea;

a method that was invariably safer, cheaper and quicker.

According to David Gates without the Royal Navy, Great Britain's campaign in Spain and Portugal could never have been waged

and certainly not with the success that was eventually achieved.

He writes: "As well as ferrying troops to and from

the war zone, the fleet transported virtually all the gold, equipment, food and munitions used by the Allied armies

and guerillas. ... Moreover, whereas the lack of any naval support of their own confined the French

to moving via the appalling Peninsular roads, the Allied forces could frequently transport men and material by sea;

a method that was invariably safer, cheaper and quicker.

This provided them with enormous advantages in the fields of logistics and strategy. ... Eternally

threatened with landings on the sea-shore, their [French] army had to detach thousands of badly needed troops to patrol beaches, garrison ports and man coastal batteries.

In 1810, for example, two Allied squadrons - based on Ferrol and Corunna -

tied down some 20,000 Imperial soldiers along the Biscay coast.

A further 20,000 soldiers were needed to invest

the naval base at Cadiz, and several thousands more spent their time fruitlessly chasing Allied detachments that constantly embarked and disembarked along

the Andalusian coast. Very few of these men ever saw an enemy ship or soldier, but they had to be deployed

to counter the possible threat of attack. Furthermore, the sea-shore guards frequently became targets in themselves. Required to patrol enormous lengths of coastline, they

were invariably thin on the ground and easy prey for amphibious forces composed of thousands of men. Many small

detachments were annihilated before assistance could arrive ..." (Gates - "The Spanish Ulcer" p 29)

During 1811 the British-Portuguese army did not share

the fate of that of Massena, was almost entirely the responsibility of the Royal Navy.

In sharp contrast to the Allied army, the French supply network was constantly disrupted by

guerilla bands and the rebellious population.

Consequently, the operations of the French army were repeatedly undermined or delayed by

shortages of such basic equipment as munitions, horses, weapons and money. Unable to rely

on their forces being adequately supplied by convoy,

French marhsals had to resort to extracting provisions locally - much to the annoyance of

the populace.

The total naval dominance lasted until 1812, when the USA interfered, albeit indirectly,

on the side of the French.

In 1812 the war with USA broke out and

American privateers (ext.link) arrived on European and African coast.

The Royal Navy was forced to devote hundreds of warships to a blockade of the American coast.

"Then the American privateers, being unmolested, ran down the coast of Africa, intercepted the provision trade from

the Brazils, one of the principal resources of the army, and emboldened by impunity infested the coast

of Portugal, captured 14 ships loaded with flour off the Duoro, and a large vessel in the very mouth of the Tagus.

These things happened when the ministers were censuring and interfering with Wellington's commercial transactions,

and seeking to throw the feeding of his soldiers into the hands of British speculators; as if the supply of an army

was like that of a common market !" (Napier - Vol IV, p 185)

The total naval dominance lasted until 1812, when the USA interfered, albeit indirectly,

on the side of the French.

In 1812 the war with USA broke out and

American privateers (ext.link) arrived on European and African coast.

The Royal Navy was forced to devote hundreds of warships to a blockade of the American coast.

"Then the American privateers, being unmolested, ran down the coast of Africa, intercepted the provision trade from

the Brazils, one of the principal resources of the army, and emboldened by impunity infested the coast

of Portugal, captured 14 ships loaded with flour off the Duoro, and a large vessel in the very mouth of the Tagus.

These things happened when the ministers were censuring and interfering with Wellington's commercial transactions,

and seeking to throw the feeding of his soldiers into the hands of British speculators; as if the supply of an army

was like that of a common market !" (Napier - Vol IV, p 185)

The French naval vessels, backed by a powerful force of privateers and American ships,

instigated a relentless campaign againt British vessels, and by summer 1814, about 800 merchantmen had been sunk, damaged or captured, many of them in home waters.

Gates writes: "With ships like USS

'Argus' rampaging up and down the English Channel (ext.link), Wellington's formerly smooth supply system was appreciably

disrupted."

Moore's failed campaign.

The British were defeated at

Corunna

and forced to leave Spain.

General Sir Moore's corps arrived at Maceira Bay on the 24 August with the following troops:

Fraser's Division (4 British btns.), Murray's Division (4 German btns.), Paget's Division

(2 German and 1 British btn. and German cavalry regiment), and artillery (2 German and 2

British batteries).

General Sir Moore's corps arrived at Maceira Bay on the 24 August with the following troops:

Fraser's Division (4 British btns.), Murray's Division (4 German btns.), Paget's Division

(2 German and 1 British btn. and German cavalry regiment), and artillery (2 German and 2

British batteries).

This campaign began as follow: General Moore left a garrison in Lisbon of 10,000 men and entered Spain with 20,000 to

aid the Spanish. His command was to be augmented with 16,000 more under General Baird being sent through Corunna.

Moore hoped that his action will disrupt Napoleon's offensive and draw his attention away from Portugal.

In the beginning of September arrived reinforcements. The British government designated another army (under Baird) to go to Peninsula and decided to assist the Spanish armies in the field.

Moore arrived at Salamanca and after hearing of the defeat of Blake's Spaniards at Espinosa, the annihilation of Army of Estremadura and the destruction of Castaños at Tudela, he was having second thoughts about his own campaign. He rejected the entreaties of the Supreme Junta and ordered a withdrawal to Portugal.

On Dec 5th however Moore received news that the population of Madrid offered resistance to the French army. A letter arrived from General La Romana, in which the Spaniard assured Moore that he had rallied Blake's divisions and was ready to take the field with 23,000 men.

A captured dispatch revealed the isolation of Marshal Soult's scattered corps. Moore decided to strike a blow at the French communication lines at Burgos and guarding them Soult's troops and thus oblige Napoleon to relinquish his grip on Madrid. However, much of the information Moore received was incorrect. Madrid had surrendered to Napoleon on Dec 4th and on Dec 11th Moore received gloomy information about it.

Napoleon already had been aware of Moore's army at Salamanca and was hurrying northwards. On Dec 19th three British deserters from the 60th Foot (actually they were Frenchmen captured at Trafalgar and enlisted in the British army) reached the French outposts with news that Moore's army had been in Salamanca as late as Dec 13th.

However, the chances of catching the British were slim. "Setting the weather aside, Moore was so far to the north that it was unlikely that a force from Madrid would ever have been able to cut him off.

The emperor's only chance, indeed, was that his opponent would be caught unawares, but Moore was well aware of the danger and fled westwards as soon as he got news that Napoleon was on the march, whilst he had also long since requested that his transports should be sent round from Lisbon to La Corunna. Vigorous action on the part of Soult, it is true, might just have slowed Moore down enough to allow Napoleon's forces to get behind him, but the marshal elected to wait for the first reinforcements that were being sent up to him from Burgos and then was slowed down by pouring rain ..." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War")

Napoleon already had been aware of Moore's army at Salamanca and was hurrying northwards. On Dec 19th three British deserters from the 60th Foot (actually they were Frenchmen captured at Trafalgar and enlisted in the British army) reached the French outposts with news that Moore's army had been in Salamanca as late as Dec 13th.

However, the chances of catching the British were slim. "Setting the weather aside, Moore was so far to the north that it was unlikely that a force from Madrid would ever have been able to cut him off.

The emperor's only chance, indeed, was that his opponent would be caught unawares, but Moore was well aware of the danger and fled westwards as soon as he got news that Napoleon was on the march, whilst he had also long since requested that his transports should be sent round from Lisbon to La Corunna. Vigorous action on the part of Soult, it is true, might just have slowed Moore down enough to allow Napoleon's forces to get behind him, but the marshal elected to wait for the first reinforcements that were being sent up to him from Burgos and then was slowed down by pouring rain ..." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War")

Realising what Moore had in mind, the Emperor saw a golden opportunity to swing into his rear, while Soult contained him frontally. The British army would be encircled and destroyed.

Napoleon took his army towards the Guadarrama Pass and in appalling weather led through the mountains.

On December 30th, the main French army began crossing the Esla River, and Marshal Soult entered Leon. Napoleon pushed forward. Unfortunately the cares of his vast empire were plucking at his coattails. He received news of political intrigues at Paris and that Austria was again mobilising her large army.

The Emperor was needed in France. On January 17th he began a breakneck ride for Paris, arriving there on the 24th.

Soult was left with only 16,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry. He pressed Moore hard, but ran no unnecessary risks.

The British general sent his light troops through Orense to Vigo, where they embarked on the 17th. General La Romana moved southward. At midnight, after the destruction of the remaining stores and 500 horses, Moore ordered his army back on the Corunna road.

Other than for the rearguard and the Guards the discipline of many of the British regiments

disintegrated. Moore finally halted in Corunna.

Marshal Soult began to collect his scattered troops for battle. However, the appearance of British warships and transport fleet and the detonation of 4,000 barrels of gunpowder - convinced the Frenchman that the British's escape was imminent. Realising that he could delay no longer, re resolved to attack immediately.

In the battle Moore was mortally wounded.

General Hope pressed the embarkation. Benjamin Miller writes: "As we drifted down the harbour we saw hundreds of our

soldiers, which had been doing duty in the garrison, sitting on the rocks by the water's side … waving their hats and calling for

the boats to take them off …" The British had almost finished the embarkation by morning, when French artillery came into

action from cliffs overlooking the bay. Cpt. Gordon writes: "The French … opened a cannonade upon the shipping in the harbour, which caused great confusion amongst the transports. Many were obliged to cut their cables, some suffered damage by running foul of each other, and 5 or 6 were abandoned by their crews and drifted on shore."

The expedition reached England between 21 and 23 June, having lost some 8,800 men. "The people of Portsmouth looked

on in horror at the spectacle that was emerging from the harbour. The British expeditionary force had returned home, but

there was no grand parade through the streets, no pomp or colour, no tale of victory. What appeared seemed rather to be

the mere wreckage of an army." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War" p 140)

Soult was left with only 16,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry. He pressed Moore hard, but ran no unnecessary risks.

The British general sent his light troops through Orense to Vigo, where they embarked on the 17th. General La Romana moved southward. At midnight, after the destruction of the remaining stores and 500 horses, Moore ordered his army back on the Corunna road.

Other than for the rearguard and the Guards the discipline of many of the British regiments

disintegrated. Moore finally halted in Corunna.

Marshal Soult began to collect his scattered troops for battle. However, the appearance of British warships and transport fleet and the detonation of 4,000 barrels of gunpowder - convinced the Frenchman that the British's escape was imminent. Realising that he could delay no longer, re resolved to attack immediately.

In the battle Moore was mortally wounded.

General Hope pressed the embarkation. Benjamin Miller writes: "As we drifted down the harbour we saw hundreds of our

soldiers, which had been doing duty in the garrison, sitting on the rocks by the water's side … waving their hats and calling for

the boats to take them off …" The British had almost finished the embarkation by morning, when French artillery came into

action from cliffs overlooking the bay. Cpt. Gordon writes: "The French … opened a cannonade upon the shipping in the harbour, which caused great confusion amongst the transports. Many were obliged to cut their cables, some suffered damage by running foul of each other, and 5 or 6 were abandoned by their crews and drifted on shore."

The expedition reached England between 21 and 23 June, having lost some 8,800 men. "The people of Portsmouth looked

on in horror at the spectacle that was emerging from the harbour. The British expeditionary force had returned home, but

there was no grand parade through the streets, no pomp or colour, no tale of victory. What appeared seemed rather to be

the mere wreckage of an army." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War" p 140)

With the Spanish armies defeatd and the British driven from the country, the winter 1808

seemed full of promise for the French troops. The projected invasion of Portugal - delayed by

Moore's interference - could now go ahead.

However, the interminable guerilla warfare continued to occupy vast numbers of French troops

and the ever resilient Spaniards were soon raising new troops to fling into the fray.

Meanwhile fresh British troops were landing in Peninsula. Edward Costello of 95th Rifles writes:

"... after a tolerably pleasant voyage we anchored off Lisbon [28 June 1809]. From thence, in a few days, we proceeded in open boats up the River Tagus, and

landed about 4 miles from Santarem, where we encamped for the night. On the following day we marched into the city

of Santarem amid the cheers of its inhabitants, who welcomed us with loud cries

Viva os Ingleses valerosos !"

(Costello - "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" p 17)

On landing at Mondego Bay, Wellington (Wellesley), heard the welcome news of the great Spanish

victory at Baylen and, later, General Spencer arrived with units drawn from the Mediterranean.

Wellington's long and successful campaign.

"Viva os Ingleses valerosos !"

Wellington raised the reputation of the British army

to a level unknown since Marlborough.

By May 1809, the French armies were victorious almost everywhere in Spain.

Victor advanced on Badajoz, defeating Cuesta at Medellin. Soult occupied northern Portugal,

but halted at Oporto to refit his army before advancing on Lisbon. In April Wellesley took

command of the British army in Portugal, plus a new, British-trained Portuguese army.

Wellington was a skilfull tactician, and later he earned reputation for being a cautious general

who only fought defensive actions from positions of overwhelming strength (named by some Fabius The Cunctator).

By May 1809, the French armies were victorious almost everywhere in Spain.

Victor advanced on Badajoz, defeating Cuesta at Medellin. Soult occupied northern Portugal,

but halted at Oporto to refit his army before advancing on Lisbon. In April Wellesley took

command of the British army in Portugal, plus a new, British-trained Portuguese army.

Wellington was a skilfull tactician, and later he earned reputation for being a cautious general

who only fought defensive actions from positions of overwhelming strength (named by some Fabius The Cunctator).

As strategist Wellington was one of the best in Europe. Striking north, he surpised Soult and drove him into the interior.

With Portugal in revolt all around him, Soult seemed doomed, but escaped by a daring march

through the mountains to Orense. Wellesley then turned on Victor and advanced up the Tagus River together with Cuesta.

Victor retired to Talavera, where Joseph joined him with the French reserves.

Wellesley repulsed Victor in a 2-day battle, but had to retreat hurriedly when Soult, Ney,

and Mortier emerged from the mountains to his left rear.

In 1810 Soult rapidly cleared all of southern Spain except Cadiz, which he left Victor to

blockade. Massena took Ciudad Rodrigo, and forced Wellington back through Almeida to Busaco,

where Wellington offered battle. Goaded by his headstrong corps commanders, Massena made an

unsuccessful frontal attack. The next day, he turned Wellington's flank, and the latter

thereupon retired - devastating the countryside as he went - into a previously fortified

position called the "Lines of Torres Verdes."

In 1810 Soult rapidly cleared all of southern Spain except Cadiz, which he left Victor to

blockade. Massena took Ciudad Rodrigo, and forced Wellington back through Almeida to Busaco,

where Wellington offered battle. Goaded by his headstrong corps commanders, Massena made an

unsuccessful frontal attack. The next day, he turned Wellington's flank, and the latter

thereupon retired - devastating the countryside as he went - into a previously fortified

position called the "Lines of Torres Verdes."

De Rocca writes: "The French sought, in vain, to provoke Lord Wellington to come out and give

them battle. That modern Fabius

[Fabius The Cunctator] remained

immovable in his lines, and coolly contemplated

his enemies below him, from the top of his high rocks." (de Rocca, - p 177)

In 1811 Massena grimly held his starving army before Lisbon for a month, then fell back

to Santarem, where Wellington did not choose to attack him. In March, with supplies exhausted,

Massena managed a skillful retreat on Salamanca, with Ney again displaying a savage talent for

rear-guard fighting. Soult, meanwhile captured Badajoz. Victor was defeated at Barrosa by

Graham, but the cowardice of La Pena made it a fruitless success, and Victor soon renewed the

blockade.

In April, Wellington besieged Almeida. Massena advanced to its relief, attacking Wellington

at Fuentes de Onoro (ext.link). The French claimed victory, because they won the passage at Poco

Velho, cleared the wood, turned the British right flank, obliged the cavalry to retire,

and forced Wellington to relinquish 3 miles of ground. The British also claimed victory because the village of Fuentes was in their hands and their

object (covering the blockade of Almeida) was attained. The French, without being in any

manner molested, retired.

Outgeneraled, Wellington was saved only by the innate toughness of his

troops and Bessieres' failure to support Massena. Bessiers led the cavalry of Imperial Guard

and refused to obey orders from Massena. After this battle, the Almeida garrison

escaped through the British lines by a night march. Napier writes: "In the battle of Fuentes Onoro, more errors than skill were

observable on both sides ..." (Napier - Vol III, p 87)

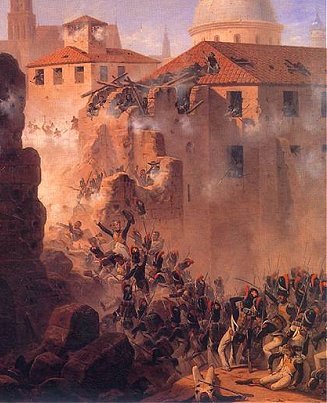

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

Part of Wellington's army had besieged Badajoz, until Soult forced it to retire on Albuera.

There, Soult outmaneuvered Beresford, but could not quite win the battle, and so retired to

Seville. Wellington joined Beresford and unskillfully renewed the siege of Badajoz.

Marmont (who had replaced Massena) joined Soult, and Wellington retired - but soon appeared

before Ciudad Rodrigo. In September, Marmont crowded him back and reprovisioned that fortress.

During 1810-1811, the majority of the French annual conscript calls of 180.000-200.000

conscripts went to Spain and dramatically lowered the quality of the French troops.

The lack of seasoned officers caused replacement battalions and squadrons returning to

Spain to be led by inexperienced officers of reserve formations and second rate troops.

Additionally Napoleon considered the war in Spain so insignificant that he rarely bothered

to bring to it his military genius, relying instead on his marshals and simultaneously

launching his disastrous Russian campaign of 1812.

The French armies were commanded by the bowlegged and grumpy Soult, the growing bald and

irresponsible Ney, and the well educated Marmont who outmarched and often outmaneuvered

Wellington.

Between September 19 and October 21 Wellington besieged Burgos but failed to

capture it and retreated to Portugal being pursued by the enemy and losing several thousands men

Napier writes: "The French gathered a good spoil of baggage ... According to muster-rolls, about 1,000

Anglo-Portuguese were killed, wounded and missing ... but this only refers to loss in action; Hill's loss between the Tagus

and the Tormes was, including stragglers, 400, and the defence of Alba de Tormes cost one hundred.

If the Spanish regulars and partidas marching with the two armies be reckoned to have lost a 1,000

which considering their want of discipline is not exaggerated, the whole loss previous to the French passage of the Tormes will amount perhaps to 3,000 men.

But the loss between the Tormes and the Agueda was certainly greater, for nearly 300 were killed and wounded at the Huebra; many

stragglers died in the woods, and Jourdan said the prisoners, Spanish, Portuguese and English, brought to Salamanca up to the

20th Nov, were 3,520. The whole loss of the double retreat cannot therefore be set down at less than 9,000,

including the loss in the siege.

Some French writers have spoken of 10,000 being taken between the Tormes and the Agueda,

and Souham estimated the previous loss, incl. the siege of Burgos, at 7,000. But the King in his dispatches

called the whole loss 12,000, including therein the garrison of Chinchilla, and he observed that if the cavalry

generals, Soult [not the marshal] and Tilley, had followed the allies vigorously from Salamancathe loss would

have been much greater. ... On the other hand English authors have most unaccountably reduced the British loss to as many

hundreds." (Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814" Vol IV, p 155)

Despite the heavy losses suffered during retreat, the year of 1812 was a good year for

Wellington, his troops captured Cuidad Rodrigo and Badajoz and defeated Marmont at Salamanca.

The effect of Salamanca was to convince the British Government finally that the war in Spain should be continued.

This battle partially dispelled Wellington’s reputation for being a cautious general who only fought defensive actions from

positions of overwhelming strength. For Napoleon however, losing in Spain in 1812 or 1813 would have meant little

if there was a decisive victory in Germany or Russia.

In August Wellington entered Madrid. By the way, one of several acts that soured relations between the

British and the Spanish during the Peninsula War was the destruction of the famous ceramic

factory in Madrid, wool factory, and Roman Bridge at Alcantara by Wellington's troops.

In 1813 Wellington's army advanced against Joseph and Jourdan.

In June Wellington (75,000-90,000) he routed the French (50,000-60,000) at Vittoria.

After Vittoria Wellington failed to pursue effectively and the French recovered.

He now shortened his communications by shifting his base of operations to the northern

Spain coast, and began operations against san Sebastian and Pampeluna, at first unsuccessfully. Soult was given command of all French troops in Spain and advanced through western Pyrenees, but was finally repulsed. Wellington captured San Sebastian, later invading southern France as far as Bayonne.

Soult fought and almost won at Toulouse, the last battle of the war.

Suchet evacuated Valencia, but defeated two British expeditions from Sicily.

Enjoying many advantages over the French, Wellington achieved a record of victory perhaps

unmatched in the history of the British army. The British infantry performed gallantly especially

when placed on a strong defensive position. Wellington's Portuguese and German troops

were steady and respected by British and French alike. In the English speaking world, Wellington's campaign in Peninsula became the most popular napoleonic campaign among

wargamers.

Enjoying many advantages over the French, Wellington achieved a record of victory perhaps

unmatched in the history of the British army. The British infantry performed gallantly especially

when placed on a strong defensive position. Wellington's Portuguese and German troops

were steady and respected by British and French alike. In the English speaking world, Wellington's campaign in Peninsula became the most popular napoleonic campaign among

wargamers.

However, despite the advantages and victories in pitched battles, Wellington's campaign in

Peninsula was "the most protracted campaign of the period". Claims were made that "the Peninsular War

had been pursued with insufficient vigour."

Battles alone don't win this type of wars. British military historian Hart writes:

"... the presence of the British Expeditionary Corps was an essential foundation... Wellington's battles were materially the least effective part of the operations.

By them he [Wellington] inflicted a total loss of some 45,000 men only - counting killed,

wounded and prisoners - on the French during the 5 years' campaign... whereas Marbot reckoned

that the number of French deaths alone during this period averaged 100 a day.

Hence it is a clear deduction that the overwhelming majority of the losses which drained

the French strength, and their morale still more, was due to the operations of the

guerillas..." (Hart - "Strategy" 1991, pp 110-111)

Battles alone don't win this type of wars. British military historian Hart writes:

"... the presence of the British Expeditionary Corps was an essential foundation... Wellington's battles were materially the least effective part of the operations.

By them he [Wellington] inflicted a total loss of some 45,000 men only - counting killed,

wounded and prisoners - on the French during the 5 years' campaign... whereas Marbot reckoned

that the number of French deaths alone during this period averaged 100 a day.

Hence it is a clear deduction that the overwhelming majority of the losses which drained

the French strength, and their morale still more, was due to the operations of the

guerillas..." (Hart - "Strategy" 1991, pp 110-111)

"... the Spanish 'nation in arms' ... may have lacked the polished

professionalism of the British Light Division but, in the long run, they probably inflicted

considerably more damage on the French forces than all of Wellington's pitched battles combined.

The sieges of Gerona alone cost the Imperial armies over 20,000 casualties and, exclusively

from sickness and guerilla raids, the French forces in the Peninsula lost approx. 100 men per

day for over 4 years, a total of some 164,000 casualties. It is, therefore, easy to see how

the war in Spain bled the French army white ..." (- Gates)

|

1.

1.

The treaty of Tilsit in 1807 ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires

which rendered the rest of Europe almost powerless.

The treaty of Tilsit in 1807 ended war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires

which rendered the rest of Europe almost powerless.

Junot thrusted down the Tagus Valley to Lisbon. The French troops found the terrain barren

and inhospitable. According to wikipedia.org Portugal is split in two by its main river,

the Tagus (Tejo). Northern landscape is mountainous in the interior areas with plateaus. The South area between the

Tagus and the Algarve features mostly rolling plains with a climate somewhat warmer and drier than the cooler and rainier north.

Portugal is one of the warmest European countries. In mainland Portugal, yearly

temperature averages are about 15º C (55° F) in the north and 18ºC (64°F) in the south.

Junot thrusted down the Tagus Valley to Lisbon. The French troops found the terrain barren

and inhospitable. According to wikipedia.org Portugal is split in two by its main river,

the Tagus (Tejo). Northern landscape is mountainous in the interior areas with plateaus. The South area between the

Tagus and the Algarve features mostly rolling plains with a climate somewhat warmer and drier than the cooler and rainier north.

Portugal is one of the warmest European countries. In mainland Portugal, yearly

temperature averages are about 15º C (55° F) in the north and 18ºC (64°F) in the south.

On picture: captain of Portuguese Cacadores in 1811, by Carlos Ribeiro.

On picture: captain of Portuguese Cacadores in 1811, by Carlos Ribeiro. The ease with which Junot's troops had seized Portugal lulled the Emperor into a

false sense of conquest. He was excessively optimistic in calculating some of the benefits

he hoped to gain from Spain.

Doubtlessly fascinated by Spain's history of splendour, Napoleon was convinced that the

country was excessively wealthy when, in fact, she was virtually bankrupt.

According to Summerville “In 1807 Spain was one of the most backward nations of Europe …”

The ease with which Junot's troops had seized Portugal lulled the Emperor into a

false sense of conquest. He was excessively optimistic in calculating some of the benefits

he hoped to gain from Spain.

Doubtlessly fascinated by Spain's history of splendour, Napoleon was convinced that the

country was excessively wealthy when, in fact, she was virtually bankrupt.

According to Summerville “In 1807 Spain was one of the most backward nations of Europe …”

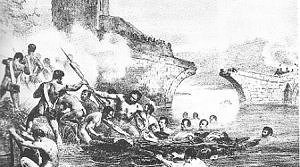

On picture: "the French arrived [at Tordesillas], sixty ... headed by Captain Guingret, a daring man,

formed a small raft to hold their arms and clothes, and plunged into the watre, holding their swords with their teeth,

swimming and pushing their raft before them. Under protection of a cannonande they crossed this

great river, though it was in full and strong water, and the weather very cold, and having reached the other side,

naked as they were, stormed the tower: the Brunswick regiment then abandoned the wood, and the gallant Frenchmen

remained masters of the bridge." (Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814"

Vol IV, p 138)

On picture: "the French arrived [at Tordesillas], sixty ... headed by Captain Guingret, a daring man,

formed a small raft to hold their arms and clothes, and plunged into the watre, holding their swords with their teeth,

swimming and pushing their raft before them. Under protection of a cannonande they crossed this

great river, though it was in full and strong water, and the weather very cold, and having reached the other side,

naked as they were, stormed the tower: the Brunswick regiment then abandoned the wood, and the gallant Frenchmen

remained masters of the bridge." (Napier - "History of the War in the Peninsula 1807-1814"

Vol IV, p 138)

According to David Gates there was a tremendous variety in the quality of soldiers

that Napoleon committed to the Peninsula at various stages of the war.

The first French army to march into Spain in 1808, for example, was predominantly composed of

inexperienced conscripts.

According to David Gates there was a tremendous variety in the quality of soldiers

that Napoleon committed to the Peninsula at various stages of the war.

The first French army to march into Spain in 1808, for example, was predominantly composed of

inexperienced conscripts.

In Peninsula the French met serious problems while the Emperor seemed to ignore the food

question. In 1812 Marshal Marmont complained to Napoleon: "... the English army is always concentrated and can always be moved,

because it has an adequate supply of money and transport. 7,000 to 8,000 pack mules bring

up its daily food ... His Majesty may judge from this fact the comparison between their

means and our's -we have not 4 day's food in any of our magazines, we have no transport,

we cannot draw requisitions from the most wretched village without sending

thither a foraging party of 200 strong; to live from day to day, we have to scatter

detachments to vast distances, and always to be on the move ...

Lord Wellington is quite aware that I have no magazines, and is acquinted with the

immensely difficult character of the country, and its complete lack of food resources ... He knows that my army is not in a position to cross the Coa, even if nobody opposes me, and that if we did so we should have to turn back at the

end of 4 days, unable to carry on the campaign ..."

In Peninsula the French met serious problems while the Emperor seemed to ignore the food

question. In 1812 Marshal Marmont complained to Napoleon: "... the English army is always concentrated and can always be moved,

because it has an adequate supply of money and transport. 7,000 to 8,000 pack mules bring

up its daily food ... His Majesty may judge from this fact the comparison between their

means and our's -we have not 4 day's food in any of our magazines, we have no transport,

we cannot draw requisitions from the most wretched village without sending

thither a foraging party of 200 strong; to live from day to day, we have to scatter

detachments to vast distances, and always to be on the move ...

Lord Wellington is quite aware that I have no magazines, and is acquinted with the

immensely difficult character of the country, and its complete lack of food resources ... He knows that my army is not in a position to cross the Coa, even if nobody opposes me, and that if we did so we should have to turn back at the

end of 4 days, unable to carry on the campaign ..."

Spanish soldiers, picture by Funcken:

Spanish soldiers, picture by Funcken: "It has been the practice of many historians to pour scorn on just about everything the

Spanish forces did and a good deal of this criticism is justified. However, the fact remains that without the

Spanish Army it is doubtful that the Allies would have won the war. Whilst it is true that

their soldiers and generals performed badly on a large number of occasisons,

it is also the case that Spanish units behaved outstandngly well on others: Baylen, Tamames

and Alcaniz are all examples of clear-cut Peninsular victories by indigenous armies and,

at San Marcial, in 1813, a major Imperial offensive was brought ot a complete standstill by the determined Spanish troops that lay in its path.

Indeed, by the later months of the war, the Spanish were providing some units of extremely

good quality ...

"It has been the practice of many historians to pour scorn on just about everything the

Spanish forces did and a good deal of this criticism is justified. However, the fact remains that without the

Spanish Army it is doubtful that the Allies would have won the war. Whilst it is true that

their soldiers and generals performed badly on a large number of occasisons,

it is also the case that Spanish units behaved outstandngly well on others: Baylen, Tamames

and Alcaniz are all examples of clear-cut Peninsular victories by indigenous armies and,

at San Marcial, in 1813, a major Imperial offensive was brought ot a complete standstill by the determined Spanish troops that lay in its path.

Indeed, by the later months of the war, the Spanish were providing some units of extremely

good quality ...  Murat, a simple and unsophisticated soldier, squabbled with the Regency Junta by

Ferdinand to govern in the absence of the king.

On 2nd May disorders began in all of Madrid, and only in the evening the French were

again masters of the city. The French were attacked by the people of Madrid because

it protected the hated Godoy (one of the ministers of the Spanish sovereign Charles

IV who had taken shelter in France). Godoy's house was broken into and sacked, his

Guard hussars dispersed by the King's body-guard.

Murat, a simple and unsophisticated soldier, squabbled with the Regency Junta by

Ferdinand to govern in the absence of the king.

On 2nd May disorders began in all of Madrid, and only in the evening the French were

again masters of the city. The French were attacked by the people of Madrid because

it protected the hated Godoy (one of the ministers of the Spanish sovereign Charles

IV who had taken shelter in France). Godoy's house was broken into and sacked, his

Guard hussars dispersed by the King's body-guard.

Chlapowski of Napoleon's Guard Lighthorse writes: "There were no more than 4,000 infantry in Madrid, the Fusiliers of the Guard,

12 artillery pieces and 200 Mamelukes at the Royal Palace. The cavalry of the Guard was stationed in villages 1 to 1.5 miles from the city ...

The inhibitants collected in the key areas around the city, armed with long swords and knives. Many had firearms.

Most of them gathered in the city center at the square called the Puerto del Sol, but they were also milling around in the side streets.

They shot at officers riding past with orders. Murat's ADC, Gobert, was stabbed several times in the legs as he fought his way through the Puerto del Sol, but despite this

he made it right across town to the Fusiliers, who straight away marched to the arsenal. They took it without a shot and dispersed the crowd which had taken a few old artillery pieces, but did not know how to fire them.

About 2,000 peasants and citizens were captured."

(Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p. 36, translated by Tim Simmons)

Chlapowski of Napoleon's Guard Lighthorse writes: "There were no more than 4,000 infantry in Madrid, the Fusiliers of the Guard,

12 artillery pieces and 200 Mamelukes at the Royal Palace. The cavalry of the Guard was stationed in villages 1 to 1.5 miles from the city ...

The inhibitants collected in the key areas around the city, armed with long swords and knives. Many had firearms.

Most of them gathered in the city center at the square called the Puerto del Sol, but they were also milling around in the side streets.

They shot at officers riding past with orders. Murat's ADC, Gobert, was stabbed several times in the legs as he fought his way through the Puerto del Sol, but despite this

he made it right across town to the Fusiliers, who straight away marched to the arsenal. They took it without a shot and dispersed the crowd which had taken a few old artillery pieces, but did not know how to fire them.

About 2,000 peasants and citizens were captured."

(Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer" p. 36, translated by Tim Simmons)

Baron de Marbot described what he saw: "While defending the dismounted dragoon,

I had received a blow from a dagger in my jacket sleeve, and two of my troopers

had been slightly wounded. My orders were to bring the divisions to the Puerta del Sol,

and they started at a gallop. The squadrons of the guard, commanded by the celebrated

Daumesmil, marched first, with the Mamelukes leading.

Baron de Marbot described what he saw: "While defending the dismounted dragoon,

I had received a blow from a dagger in my jacket sleeve, and two of my troopers

had been slightly wounded. My orders were to bring the divisions to the Puerta del Sol,

and they started at a gallop. The squadrons of the guard, commanded by the celebrated

Daumesmil, marched first, with the Mamelukes leading.

The civilian population were treated by the French in a manner that ranged from the merely

boisterous to downright brutal. Rape, pillage, murder, thievery, drunkenness and anything

else were common. "... the number of towns whose inhabitants were accused of firing on the

French - most notably, Medina de Rio Seco and Chinchon - experienced appaling massacres.

To decribe this policy as genocide - a term that can certainly be applied in other contexts,

most notably the Vendee - would be to go too far.

The civilian population were treated by the French in a manner that ranged from the merely

boisterous to downright brutal. Rape, pillage, murder, thievery, drunkenness and anything

else were common. "... the number of towns whose inhabitants were accused of firing on the

French - most notably, Medina de Rio Seco and Chinchon - experienced appaling massacres.

To decribe this policy as genocide - a term that can certainly be applied in other contexts,

most notably the Vendee - would be to go too far.

Wherever the French soldiers went the Church's property was expropriated and the religious

orders dissolved. The French did not or could not distinguish between guerrilla and civilian.

Hence innocent civilians killed in reprisal or revenge.

Wherever the French soldiers went the Church's property was expropriated and the religious

orders dissolved. The French did not or could not distinguish between guerrilla and civilian.

Hence innocent civilians killed in reprisal or revenge.

The Spaniards rarely surrendered a city without a siege, and usually fought

fiercely even after the city walls were breached.

The Spaniards rarely surrendered a city without a siege, and usually fought

fiercely even after the city walls were breached.

"It would be impossible correctly to describe the spectacle which was then presented by the

unfortunate city of Saragossa. The hospitals could no longer admit any more sick or wounded.

The burying grounds were too small for the number of dead carried thither;

the corpses sewed up in cloth bags were lying by hundreds at the doors of the several

churches." (Suchet - "War in Spain")

"It would be impossible correctly to describe the spectacle which was then presented by the

unfortunate city of Saragossa. The hospitals could no longer admit any more sick or wounded.

The burying grounds were too small for the number of dead carried thither;

the corpses sewed up in cloth bags were lying by hundreds at the doors of the several

churches." (Suchet - "War in Spain")

In May 1808, the whole Spain was up in arms against the French.

Juntas led the revolts from Aragon to Galicia, and from Catalonia to Asturia.

Despite this situation Murat continued to send relatively optimistic reports to Napoleon

and so, the Emperor was badly misinformed about the true nature of the war.

To deal with the supposedly weak and isolated trouble spots, Napoleon

drew up a plan which Murat put into operation. Large army was to be kept at and around

Madrid, while Dupont's corps was to move on Cordova and Seville.

In May 1808, the whole Spain was up in arms against the French.

Juntas led the revolts from Aragon to Galicia, and from Catalonia to Asturia.

Despite this situation Murat continued to send relatively optimistic reports to Napoleon

and so, the Emperor was badly misinformed about the true nature of the war.

To deal with the supposedly weak and isolated trouble spots, Napoleon

drew up a plan which Murat put into operation. Large army was to be kept at and around

Madrid, while Dupont's corps was to move on Cordova and Seville.

On 19th July 1808 the Spanish troops defeated Dupont at Baylen (Bailén, Bailen).

The battle went wrong for the French already in the beginning. "The Spanish General had 25.000

regular infantry, 2,000 cavalry and a very heavy train of artillery. Large bodies of armed peasantry,

commanded by officers of the line, attended this army, and the numbers varied from day to day, but the whole multitude that advanced towards the Guadalquivir could not have been less

than 50,000 men." (Napier - p 90)

On 19th July 1808 the Spanish troops defeated Dupont at Baylen (Bailén, Bailen).

The battle went wrong for the French already in the beginning. "The Spanish General had 25.000

regular infantry, 2,000 cavalry and a very heavy train of artillery. Large bodies of armed peasantry,

commanded by officers of the line, attended this army, and the numbers varied from day to day, but the whole multitude that advanced towards the Guadalquivir could not have been less

than 50,000 men." (Napier - p 90)

The news about French defeat at Baylen sent shock waves throughout Europe. The Spanish regiments proclaimed themselves the "conquerors of the conquerors of Austerlitz."

Napoleon was furious: "The capitulation of Baylen ruined everything.

In order to save his wagons of booty, Dupont commited his soldiers to the disgrace

of a surrender that is without parallel."

The news about French defeat at Baylen sent shock waves throughout Europe. The Spanish regiments proclaimed themselves the "conquerors of the conquerors of Austerlitz."

Napoleon was furious: "The capitulation of Baylen ruined everything.

In order to save his wagons of booty, Dupont commited his soldiers to the disgrace

of a surrender that is without parallel."

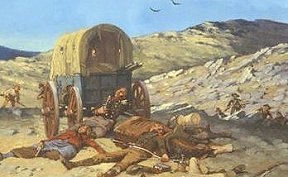

Picture: guerillas attack on French convoy. Picture by: ???

Picture: guerillas attack on French convoy. Picture by: ???

Napoleon, failing to grasp the nature of the revolt in Spain, issued orders to the marshals which

incl. the usual talk of 'flying columns', making examples', 'utilising the Spanish authorities' and so on.

He assumed that the French troops would be capable of holding the territory and be free to release units for service

in other theaters.

Napoleon, failing to grasp the nature of the revolt in Spain, issued orders to the marshals which

incl. the usual talk of 'flying columns', making examples', 'utilising the Spanish authorities' and so on.

He assumed that the French troops would be capable of holding the territory and be free to release units for service

in other theaters.

The guerrillas ambushed French convoys, attacked French encampments, and pounced upon, dodged,

and fought French columns. Local guides could not be trusted unless their families were held hostage for their good

behaviour. It was best to move quickly and by night. Lists of casualties included many

"ambushed" and "disappeared". Couriers and convoys could get through only under strong escort

from one fortified post to another.

The guerrillas ambushed French convoys, attacked French encampments, and pounced upon, dodged,

and fought French columns. Local guides could not be trusted unless their families were held hostage for their good

behaviour. It was best to move quickly and by night. Lists of casualties included many

"ambushed" and "disappeared". Couriers and convoys could get through only under strong escort

from one fortified post to another.

Likewise, on a number of occassions, Wellington owed his salvation to the intelligence role

of the guerillas. Gates writes: "Immediately after Talavera ... [Wellington] confidently marched off to attack what he believed to be only 10,000 French troops with a force of 18,000-strong.

In fact, the Imperial 'detachment' consisted of three entire army corps and numbered well over

50,000 men. Had Wellington not received a timely warning of his miscalculation

from the guerillas, it is extremely probable that in the ensuing battle both he and the British army would

have ceased to be active factors in the scenarios of the Peninsular war. As it was, he was able to

retreat in time." (- Gates, p 35)

Likewise, on a number of occassions, Wellington owed his salvation to the intelligence role

of the guerillas. Gates writes: "Immediately after Talavera ... [Wellington] confidently marched off to attack what he believed to be only 10,000 French troops with a force of 18,000-strong.

In fact, the Imperial 'detachment' consisted of three entire army corps and numbered well over

50,000 men. Had Wellington not received a timely warning of his miscalculation

from the guerillas, it is extremely probable that in the ensuing battle both he and the British army would

have ceased to be active factors in the scenarios of the Peninsular war. As it was, he was able to

retreat in time." (- Gates, p 35)

The Spaniards were fired up by priests who were terrified by the fate that had fallen upon

their brethren in France.

The Spanish clergy was hostile not only to the French atheists and occupants but also

to English "heretics". Local peasants sometimes had hidden all their kids having

been told the English would eat them.

The Spaniards were fired up by priests who were terrified by the fate that had fallen upon

their brethren in France.

The Spanish clergy was hostile not only to the French atheists and occupants but also

to English "heretics". Local peasants sometimes had hidden all their kids having

been told the English would eat them.

The war was fought with

The war was fought with  "In so far as the world of the Anglo-Saxon historiography was concerned, Oman's magisterial conclusions set a seal of approval on the guerillas, the eighty years that have passed since the publication of the last volume

of his work having been accompanied by a veritable chorus of praise. On all sides the many populists who chose to write about the Peninsular War leapt to acknowledge

the exploits of the guerillas. To quote Longford, for example: 'Spain was to be saved ... not by grape-shot, greybeards and grandees, but by a hardy guerillas and the sudden flash of the knife ... Even the basic force of 200,000

veterans which Napoleon was compelled to keep, year after year, in Spain would never be safe

from the noon-day ambush and things that went bump in the night.' Charles Esdaile continues "It was not just the writers of popular history

who echoed the general refrain, however. Amongst historians of greater pretention Oman's theories

have also been accepted without question and even pushed to fresh lengths. 'It was above all,' wrote David Chandler,

'the interaction of Wellngton's operations with those of the guerilla bands that ... made the French problem wholly intractible ... Even with 320,000 men the marshals

could not both contain the diffuse ... 'war of the flea' and at the same time ... meet

Wellington's latest foray deep into their territory.'

"In so far as the world of the Anglo-Saxon historiography was concerned, Oman's magisterial conclusions set a seal of approval on the guerillas, the eighty years that have passed since the publication of the last volume

of his work having been accompanied by a veritable chorus of praise. On all sides the many populists who chose to write about the Peninsular War leapt to acknowledge

the exploits of the guerillas. To quote Longford, for example: 'Spain was to be saved ... not by grape-shot, greybeards and grandees, but by a hardy guerillas and the sudden flash of the knife ... Even the basic force of 200,000

veterans which Napoleon was compelled to keep, year after year, in Spain would never be safe

from the noon-day ambush and things that went bump in the night.' Charles Esdaile continues "It was not just the writers of popular history

who echoed the general refrain, however. Amongst historians of greater pretention Oman's theories

have also been accepted without question and even pushed to fresh lengths. 'It was above all,' wrote David Chandler,

'the interaction of Wellngton's operations with those of the guerilla bands that ... made the French problem wholly intractible ... Even with 320,000 men the marshals

could not both contain the diffuse ... 'war of the flea' and at the same time ... meet

Wellington's latest foray deep into their territory.'

On picture: in 1812 the second in command of the British army,

Lord Paget, was captured by French dragoons. In 1809 the first in command, Wellington, was

almost captured at Combat of Casa de Salinas.

On picture: in 1812 the second in command of the British army,

Lord Paget, was captured by French dragoons. In 1809 the first in command, Wellington, was

almost captured at Combat of Casa de Salinas.

According to David Gates without the Royal Navy, Great Britain's campaign in Spain and Portugal could never have been waged

and certainly not with the success that was eventually achieved.

He writes: "As well as ferrying troops to and from

the war zone, the fleet transported virtually all the gold, equipment, food and munitions used by the Allied armies

and guerillas. ... Moreover, whereas the lack of any naval support of their own confined the French

to moving via the appalling Peninsular roads, the Allied forces could frequently transport men and material by sea;

a method that was invariably safer, cheaper and quicker.

According to David Gates without the Royal Navy, Great Britain's campaign in Spain and Portugal could never have been waged

and certainly not with the success that was eventually achieved.

He writes: "As well as ferrying troops to and from

the war zone, the fleet transported virtually all the gold, equipment, food and munitions used by the Allied armies

and guerillas. ... Moreover, whereas the lack of any naval support of their own confined the French

to moving via the appalling Peninsular roads, the Allied forces could frequently transport men and material by sea;

a method that was invariably safer, cheaper and quicker.

The total naval dominance lasted until 1812, when the USA interfered, albeit indirectly,

on the side of the French.

In 1812 the war with USA broke out and

The total naval dominance lasted until 1812, when the USA interfered, albeit indirectly,

on the side of the French.

In 1812 the war with USA broke out and  General Sir Moore's corps arrived at Maceira Bay on the 24 August with the following troops:

Fraser's Division (4 British btns.), Murray's Division (4 German btns.), Paget's Division

(2 German and 1 British btn. and German cavalry regiment), and artillery (2 German and 2

British batteries).

General Sir Moore's corps arrived at Maceira Bay on the 24 August with the following troops:

Fraser's Division (4 British btns.), Murray's Division (4 German btns.), Paget's Division

(2 German and 1 British btn. and German cavalry regiment), and artillery (2 German and 2

British batteries).

Napoleon already had been aware of Moore's army at Salamanca and was hurrying northwards. On Dec 19th three British deserters from the 60th Foot (actually they were Frenchmen captured at Trafalgar and enlisted in the British army) reached the French outposts with news that Moore's army had been in Salamanca as late as Dec 13th.

However, the chances of catching the British were slim. "Setting the weather aside, Moore was so far to the north that it was unlikely that a force from Madrid would ever have been able to cut him off.

The emperor's only chance, indeed, was that his opponent would be caught unawares, but Moore was well aware of the danger and fled westwards as soon as he got news that Napoleon was on the march, whilst he had also long since requested that his transports should be sent round from Lisbon to La Corunna. Vigorous action on the part of Soult, it is true, might just have slowed Moore down enough to allow Napoleon's forces to get behind him, but the marshal elected to wait for the first reinforcements that were being sent up to him from Burgos and then was slowed down by pouring rain ..." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War")

Napoleon already had been aware of Moore's army at Salamanca and was hurrying northwards. On Dec 19th three British deserters from the 60th Foot (actually they were Frenchmen captured at Trafalgar and enlisted in the British army) reached the French outposts with news that Moore's army had been in Salamanca as late as Dec 13th.

However, the chances of catching the British were slim. "Setting the weather aside, Moore was so far to the north that it was unlikely that a force from Madrid would ever have been able to cut him off.

The emperor's only chance, indeed, was that his opponent would be caught unawares, but Moore was well aware of the danger and fled westwards as soon as he got news that Napoleon was on the march, whilst he had also long since requested that his transports should be sent round from Lisbon to La Corunna. Vigorous action on the part of Soult, it is true, might just have slowed Moore down enough to allow Napoleon's forces to get behind him, but the marshal elected to wait for the first reinforcements that were being sent up to him from Burgos and then was slowed down by pouring rain ..." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War")

Soult was left with only 16,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry. He pressed Moore hard, but ran no unnecessary risks.

The British general sent his light troops through Orense to Vigo, where they embarked on the 17th. General La Romana moved southward. At midnight, after the destruction of the remaining stores and 500 horses, Moore ordered his army back on the Corunna road.

Other than for the rearguard and the Guards the discipline of many of the British regiments

disintegrated. Moore finally halted in Corunna.

Marshal Soult began to collect his scattered troops for battle. However, the appearance of British warships and transport fleet and the detonation of 4,000 barrels of gunpowder - convinced the Frenchman that the British's escape was imminent. Realising that he could delay no longer, re resolved to attack immediately.

In the battle Moore was mortally wounded.

General Hope pressed the embarkation. Benjamin Miller writes: "As we drifted down the harbour we saw hundreds of our

soldiers, which had been doing duty in the garrison, sitting on the rocks by the water's side … waving their hats and calling for

the boats to take them off …" The British had almost finished the embarkation by morning, when French artillery came into

action from cliffs overlooking the bay. Cpt. Gordon writes: "The French … opened a cannonade upon the shipping in the harbour, which caused great confusion amongst the transports. Many were obliged to cut their cables, some suffered damage by running foul of each other, and 5 or 6 were abandoned by their crews and drifted on shore."

The expedition reached England between 21 and 23 June, having lost some 8,800 men. "The people of Portsmouth looked

on in horror at the spectacle that was emerging from the harbour. The British expeditionary force had returned home, but

there was no grand parade through the streets, no pomp or colour, no tale of victory. What appeared seemed rather to be

the mere wreckage of an army." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War" p 140)

Soult was left with only 16,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry. He pressed Moore hard, but ran no unnecessary risks.

The British general sent his light troops through Orense to Vigo, where they embarked on the 17th. General La Romana moved southward. At midnight, after the destruction of the remaining stores and 500 horses, Moore ordered his army back on the Corunna road.

Other than for the rearguard and the Guards the discipline of many of the British regiments

disintegrated. Moore finally halted in Corunna.

Marshal Soult began to collect his scattered troops for battle. However, the appearance of British warships and transport fleet and the detonation of 4,000 barrels of gunpowder - convinced the Frenchman that the British's escape was imminent. Realising that he could delay no longer, re resolved to attack immediately.

In the battle Moore was mortally wounded.

General Hope pressed the embarkation. Benjamin Miller writes: "As we drifted down the harbour we saw hundreds of our

soldiers, which had been doing duty in the garrison, sitting on the rocks by the water's side … waving their hats and calling for

the boats to take them off …" The British had almost finished the embarkation by morning, when French artillery came into

action from cliffs overlooking the bay. Cpt. Gordon writes: "The French … opened a cannonade upon the shipping in the harbour, which caused great confusion amongst the transports. Many were obliged to cut their cables, some suffered damage by running foul of each other, and 5 or 6 were abandoned by their crews and drifted on shore."

The expedition reached England between 21 and 23 June, having lost some 8,800 men. "The people of Portsmouth looked

on in horror at the spectacle that was emerging from the harbour. The British expeditionary force had returned home, but

there was no grand parade through the streets, no pomp or colour, no tale of victory. What appeared seemed rather to be

the mere wreckage of an army." (Esdaile - "The Peninsular War" p 140)

By May 1809, the French armies were victorious almost everywhere in Spain.

Victor advanced on Badajoz, defeating Cuesta at Medellin. Soult occupied northern Portugal,

but halted at Oporto to refit his army before advancing on Lisbon. In April Wellesley took

command of the British army in Portugal, plus a new, British-trained Portuguese army.

Wellington was a skilfull tactician, and later he earned reputation for being a cautious general

who only fought defensive actions from positions of overwhelming strength (named by some Fabius The Cunctator).

By May 1809, the French armies were victorious almost everywhere in Spain.

Victor advanced on Badajoz, defeating Cuesta at Medellin. Soult occupied northern Portugal,

but halted at Oporto to refit his army before advancing on Lisbon. In April Wellesley took

command of the British army in Portugal, plus a new, British-trained Portuguese army.

Wellington was a skilfull tactician, and later he earned reputation for being a cautious general

who only fought defensive actions from positions of overwhelming strength (named by some Fabius The Cunctator).

In 1810 Soult rapidly cleared all of southern Spain except Cadiz, which he left Victor to

blockade. Massena took Ciudad Rodrigo, and forced Wellington back through Almeida to Busaco,

where Wellington offered battle. Goaded by his headstrong corps commanders, Massena made an

unsuccessful frontal attack. The next day, he turned Wellington's flank, and the latter

thereupon retired - devastating the countryside as he went - into a previously fortified

position called the "Lines of Torres Verdes."

In 1810 Soult rapidly cleared all of southern Spain except Cadiz, which he left Victor to

blockade. Massena took Ciudad Rodrigo, and forced Wellington back through Almeida to Busaco,

where Wellington offered battle. Goaded by his headstrong corps commanders, Massena made an

unsuccessful frontal attack. The next day, he turned Wellington's flank, and the latter

thereupon retired - devastating the countryside as he went - into a previously fortified

position called the "Lines of Torres Verdes."

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

Picture: British infantry storming Badajoz, by Mark Churms.

Enjoying many advantages over the French, Wellington achieved a record of victory perhaps

unmatched in the history of the British army. The British infantry performed gallantly especially

when placed on a strong defensive position. Wellington's Portuguese and German troops

were steady and respected by British and French alike. In the English speaking world, Wellington's campaign in Peninsula became the most popular napoleonic campaign among

wargamers.

Enjoying many advantages over the French, Wellington achieved a record of victory perhaps

unmatched in the history of the British army. The British infantry performed gallantly especially

when placed on a strong defensive position. Wellington's Portuguese and German troops

were steady and respected by British and French alike. In the English speaking world, Wellington's campaign in Peninsula became the most popular napoleonic campaign among

wargamers.

Battles alone don't win this type of wars. British military historian Hart writes:

"... the presence of the British Expeditionary Corps was an essential foundation... Wellington's battles were materially the least effective part of the operations.

By them he [Wellington] inflicted a total loss of some 45,000 men only - counting killed,

wounded and prisoners - on the French during the 5 years' campaign... whereas Marbot reckoned

that the number of French deaths alone during this period averaged 100 a day.

Hence it is a clear deduction that the overwhelming majority of the losses which drained

the French strength, and their morale still more, was due to the operations of the

guerillas..." (Hart - "Strategy" 1991, pp 110-111)

Battles alone don't win this type of wars. British military historian Hart writes:

"... the presence of the British Expeditionary Corps was an essential foundation... Wellington's battles were materially the least effective part of the operations.

By them he [Wellington] inflicted a total loss of some 45,000 men only - counting killed,

wounded and prisoners - on the French during the 5 years' campaign... whereas Marbot reckoned

that the number of French deaths alone during this period averaged 100 a day.

Hence it is a clear deduction that the overwhelming majority of the losses which drained

the French strength, and their morale still more, was due to the operations of the

guerillas..." (Hart - "Strategy" 1991, pp 110-111)