.

"Frederick the Great's Engineer Corps had been weak

in both training and performance. He attempted to

rectify this by increasing its pay and prestige, and a

formal structure was established. In 1788 an Engineers'

Academy was opened."

Hofschroer - "Prussian Staff ..." p 18

|

Engineers.

The engineers formed an independent corps (Ingenieur-Korps) and were commanded by General-Major von Scharnhorst (between 1813 and 1815 by General-Major von Rauch).

The engineers formed an independent corps (Ingenieur-Korps) and were commanded by General-Major von Scharnhorst (between 1813 and 1815 by General-Major von Rauch).

The were three companies of pioneers for fortresses (Festungs-Pionier-Kompanien). In 1812 a fourth company was formed. In wartime from these companies were to be formed field companies. Each field company consisted of:

. . . . . . . . . . 2 officers, 1 surgeon

. . . . . . . . . . 1 sergeant-major

. . . . . . . . . . 1 armourer

. . . . . . . . . . 6 NCOs

. . . . . . . . . . 12 privates first class

. . . . . . . . . . 1 bugler

. . . . . . . . . . 40 sappers and 20 miners.

These men should be replaced in the fortress companies by recruits or reservists.

By August 1813 there were 7 field and 6 fortress companies of pioneers.

In early 1815 there were 9 field and 8 fortress companies of pioneers.

The pioneers carried swords with a saw blade, only the sergent-major and ensign had ordinary sabers. Smoothbore carabines with bayonets, and small cartridge pouches for 15 cartridges. In addition they carried hatchets, pickaxes, axes, comapass saws and spades.

NOTE: the regimental pioneers belonged to their respective (infantry) regiments and had nothing to do with the pioneers mentioned here.

In October 1813 in the Elbe province from 800 miners was formed the Mansfelder Pionier Batallion (4 field companies). The companies acted independently and were assigned to different army corps. There were no senior engineer or pioneer officers at army headquarters, only one engineer, Kapitan Vigny, serving as a staff officer plus a small topographical section.

All the engineer-officers (Ingenieur-Offiziere) were on the same rank list, but organised in 3 "brigades". These officers were attached either to the field or fortress pioneer companies.

The Guard Pioneer Detachment (Garde-Pionier-Abtheilung) was formed in 1816, not before.

Fortress War after Waterloo 1815.

The fortress war ended with Blucher

having taken 10 French fortresses.

Although the outcome of the campaign had been decided at Ligny and Waterloo, and after the signing of the Convention of Paris peace talks were in hand, the fortress war continued for some time in France. According to Peter Hofschroer, Wellington and Blucher had agreed on 23 June (few days after Waterloo) that the fortresses west of Sambre would be dealt with by Wellington's troops, and the fortresses east of that river by the Prussians.

The King of Prussia appointed Prinz August of Prussia to carry out the task of commanding the siege operations conducted by the forces under Prussian command.

He was allowed to determine which fortress he was to besiege, in what order, and in what manner.

The troops he had available for this were the II Army Corps, the North German Federal Army Corps, and the garrison of Luxembourg. The Prussians had no siege equipment at their disposal and little ammunition for the field artillery. Oberst (Colonel) von Ploosen, formerly an engineer officer in the French army, was appointed chief engineer officer for the sieges.

Additional engineer officers were made available in dribs and drabs, and two companies of the Mansfeld Pioneer Battalion, whose men were miners, were brought up in waggons. There was also number of infantry allocated to the Field Pioneer Companies.

Maubeuge was the strongest and most significant fortress on Sambre and was commanded by seasoned General Latour-Maubourg. The garrison consisted of 3,000 men (mostly National Guard) and 80 heavy cannons. The besieging Prussians had 7,700 infantry, 960 cavalry, 500 artillerymen, and 546 engineers. Prinz August decided to begin the bombardement as soon as possible. Eight 12pdrs cannons were deployed on the left bank of Sambre, 14 7pdr howitzers were placed behind the lines of the old fortified camp, and 4 10pdr howitzers were deployed further to the west, just behind the old camp. The artillery opened fire in the morning on the 29 June.

Maubeuge was the strongest and most significant fortress on Sambre and was commanded by seasoned General Latour-Maubourg. The garrison consisted of 3,000 men (mostly National Guard) and 80 heavy cannons. The besieging Prussians had 7,700 infantry, 960 cavalry, 500 artillerymen, and 546 engineers. Prinz August decided to begin the bombardement as soon as possible. Eight 12pdrs cannons were deployed on the left bank of Sambre, 14 7pdr howitzers were placed behind the lines of the old fortified camp, and 4 10pdr howitzers were deployed further to the west, just behind the old camp. The artillery opened fire in the morning on the 29 June.

Meanwhile numerous requests were sent to Wellington to send his siege train of 38 heavy guns under Colonel Dixon. This finally arrived on 8 July.

On 9 July the French fired 150pdr (!!!) mortar bombs from the fortress, but these had no effect.

For several days there was exchange of musket and artillery fire. Finally on 11 July the French commandant hoisted the white flag, requesting terms of capitulation. Under these terms he was permitted to leave the fortress with the honors of war, taking along 150 line troops and 2 cannons. The National Guard was dismissed.

The fortress war ended with Blucher having taken 10 fortresses with several hundred guns and large quantities of ammunition and powder. The breaking of the French will to resist in the northern belt was largely a Prussian achievement with Wellington's troops only having played a minor role.

Wellington appointed Prins Frederik of the Netherlands to carry out the task of commanding the siege operations conducted by the forces under Wellington's command.

For this task Frederik used Stedman's Netherland Infantry Division, the Indian Brigade, Belgian 5th Light Dragoons, and Ghigny's Cavalry Brigade. (Hofschroer - "1815: The Waterloo Campaign. The German Victory." publ. by Greenhill Books, UK)

|

1. Introduction: Prussian Artillery.

1. Introduction: Prussian Artillery.

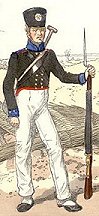

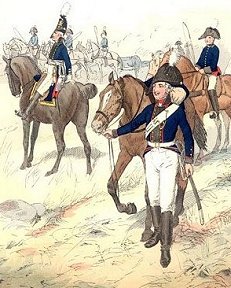

Picture: Prussian horse artillery in 1805, one year before the

disastrous Jena Campaign. From left to right: officer, gunner and driver.

Picture: Prussian horse artillery in 1805, one year before the

disastrous Jena Campaign. From left to right: officer, gunner and driver.

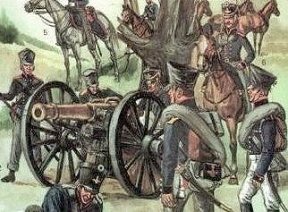

Picture: Prussian Guard artillery in 1810. Picture by Knoetel.

Picture: Prussian Guard artillery in 1810. Picture by Knoetel.

All guns, limbers and wagons were painted in medium-blue, and their metal parts were painted black. Much of Prussia's cannons and howitzers were lost in the campaign of 1806.

All guns, limbers and wagons were painted in medium-blue, and their metal parts were painted black. Much of Prussia's cannons and howitzers were lost in the campaign of 1806.

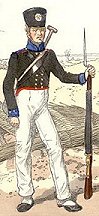

Foot gunner's uniform was similar to that of the infantryman.

He wore a "Prussian blue" coat with red turnbacks, yellow buttons and black facings. The breeches were white (for parade) or gray (for campaign).

Foot gunner's uniform was similar to that of the infantryman.

He wore a "Prussian blue" coat with red turnbacks, yellow buttons and black facings. The breeches were white (for parade) or gray (for campaign).

The foot gunners carried the infantry backpacks and bread bags.

The foot gunners carried the infantry backpacks and bread bags.

The drivers of artillery train (see picture) wore dark blue coatees with light blue cuffs and collars, red shoulder straps and white buttons.

The drivers of artillery train (see picture) wore dark blue coatees with light blue cuffs and collars, red shoulder straps and white buttons.

The engineers formed an independent corps (Ingenieur-Korps) and were commanded by General-Major von Scharnhorst (between 1813 and 1815 by General-Major von Rauch).

The engineers formed an independent corps (Ingenieur-Korps) and were commanded by General-Major von Scharnhorst (between 1813 and 1815 by General-Major von Rauch).

Maubeuge was the strongest and most significant fortress on Sambre and was commanded by seasoned General Latour-Maubourg. The garrison consisted of 3,000 men (mostly National Guard) and 80 heavy cannons. The besieging Prussians had 7,700 infantry, 960 cavalry, 500 artillerymen, and 546 engineers. Prinz August decided to begin the bombardement as soon as possible. Eight 12pdrs cannons were deployed on the left bank of Sambre, 14 7pdr howitzers were placed behind the lines of the old fortified camp, and 4 10pdr howitzers were deployed further to the west, just behind the old camp. The artillery opened fire in the morning on the 29 June.

Maubeuge was the strongest and most significant fortress on Sambre and was commanded by seasoned General Latour-Maubourg. The garrison consisted of 3,000 men (mostly National Guard) and 80 heavy cannons. The besieging Prussians had 7,700 infantry, 960 cavalry, 500 artillerymen, and 546 engineers. Prinz August decided to begin the bombardement as soon as possible. Eight 12pdrs cannons were deployed on the left bank of Sambre, 14 7pdr howitzers were placed behind the lines of the old fortified camp, and 4 10pdr howitzers were deployed further to the west, just behind the old camp. The artillery opened fire in the morning on the 29 June.