|

.

When it comes to Poles of the Napoleonic era,

consider how hard a proud people fight when

they have no homeland of their own,

and they feel that following one man,

Napoleon, is their best chance to get one.

|

Polish Army During the Napoleonic Wars.

"Poland Has Not Perished Yet,

As Long As We Are Alive."

"In the 16th century Poland had been one of the most powerful countries in Europe ...

within the space of 200 years, however, Poland had been eclipsed by its neighbours ...

Soon the country's history culture and language were extinguished and its very name abolished. In this way was the white eagle of Poland devoured

by the three black eagles of Prussia, Russia, and Austria. ...

Meanwhile the Poles looked for France, with its revolutionary ideas of Liberty,

Equality and Fraternity, as a beacon of hope. The fact France's enemies happened to be

Poland's oppressors was an obvious attraction, and many Polish soldiers volunteered for

service in the French army." (Summerville - "Napoleon's Polish Gamble" p 15)

"During the Partitions, the Poles came to see France as their truest friend in the outside world. There was some background to this: the

French and Polish royal families had intermarried, French had become the polite language of the great Polish aristocrats, and Poland

had drawn many ideas from the Enlightenment and the Revolution of 1789 before its fall. Afterwards, Napoleon supported the Polish

cause (for his own ends), and for most of the nineteenth century French governments not only welcomed Polish exiles but loudly

endorsed their calls for the restoration of independence." (- Neal Ascherson)

In 1797 in Italy was formed a Polish Legion, fighting for France against Austria.

There is hardly a more touching chapter in the world's history than the story of the

Polish Legions. The Poles hoped that by fighting on the French side against Austria,

Russia and Prussia, the contries that had partitioned Poland they could free their country.

Two years after the last dismemberment of Poland, a Polish army was formed, in Polish

uniforms, under Polish command, decorated with French cockades and wearing on the

eppaulets the inscription: "Gli uomini liberi sono fratelli." (Free men are brethren.)

The Polish soldiers without the state sung their battle-song: "Poland has not perished yet,

as long as we are alive" and fought in numerous battles and campaigns alongside the French.

In 1797 in Italy was formed a Polish Legion, fighting for France against Austria.

There is hardly a more touching chapter in the world's history than the story of the

Polish Legions. The Poles hoped that by fighting on the French side against Austria,

Russia and Prussia, the contries that had partitioned Poland they could free their country.

Two years after the last dismemberment of Poland, a Polish army was formed, in Polish

uniforms, under Polish command, decorated with French cockades and wearing on the

eppaulets the inscription: "Gli uomini liberi sono fratelli." (Free men are brethren.)

The Polish soldiers without the state sung their battle-song: "Poland has not perished yet,

as long as we are alive" and fought in numerous battles and campaigns alongside the French.

These legions however were never used for purposes related to Polish independence.

Some were posted to pacification duties in occupied Italy and in 1802-03 were drafted

with the expedition sent to crush the rebellion of Negro slaves on Santo Domingo.

They died in their thousands from swamp fever.

In 1801 at Luneville, Napoleon made peace with his enemies and all agitation on the Polish

Question was terminated. In Polish aristocratic circles, the prospect of a French alliance

was clouded by the associated threat of social revolution. Soem aristocrats were laying

plans of their won for the restoration of a united Poland under the aegis of the new Tsar

of Russia, Alexander I.

Not all Poles supported Napoleon.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko said about the Emperor: "He only thinks of himself, not about nationalist ideas, and so he could not care less

about any dreams of independence [of Poland].

He is a despot, whose sole ambition is to satisfy his personal ambition. He will create nothing of any permanence, of that I am sure."

Kosciuszko is Polish national hero, general and a leader of 1794 uprising (which bears his name) against the Russian Empire. He fought in the

American Revolutionary War as a colonel on the side of Washington. In recognition of his service he was brevetted by

the Congress to the rank of Brigadier General. He was also admitted to the prestigious Society of

Cincinnati, one of only three foreigners allowed to join. As a national hero of both Poland and the USA, Kosciuszko became the namesake of numerous places in the world:

the highest mountain in Australia, several bridges, monuments, and cities in USA.

In Poland every major town has a street or a square named after Kosciuszko.

Not all Poles supported Napoleon.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko said about the Emperor: "He only thinks of himself, not about nationalist ideas, and so he could not care less

about any dreams of independence [of Poland].

He is a despot, whose sole ambition is to satisfy his personal ambition. He will create nothing of any permanence, of that I am sure."

Kosciuszko is Polish national hero, general and a leader of 1794 uprising (which bears his name) against the Russian Empire. He fought in the

American Revolutionary War as a colonel on the side of Washington. In recognition of his service he was brevetted by

the Congress to the rank of Brigadier General. He was also admitted to the prestigious Society of

Cincinnati, one of only three foreigners allowed to join. As a national hero of both Poland and the USA, Kosciuszko became the namesake of numerous places in the world:

the highest mountain in Australia, several bridges, monuments, and cities in USA.

In Poland every major town has a street or a square named after Kosciuszko.

"In November 1806, the French armies arrived in Poznan [Posen]. The 1st Chasseurs-Cheval,

under Colonel Exelmans, who would later become a famous general, where the first to enter the [Polish] city as evening fell.

The I Squadron hurried at the trot right through the city with swords drawn, to place pickets on the other side of the Warta River, on the Warsaw and Torun [Thorn] roads.

The rest of the regiment stood peacefully in the market square, where a part of the population

came cheering to welcome them. ... The French ... after talking to the townspeaople pressing around them, they confirmed the impression already gained

from a few days march ... that they were in friendly territory. They billeted themselves peacefully around the city."

(Chlapowski / Simmons - p 8)

Marshal Murat entered Warsaw to a rapturous welcome.

He was feted by the Poles igniting vain hopes of future kingship.

"In the 16th century Poland had been one of the most powerful countries in Europe ...

within the space of 200 years, however, Poland had been eclipsed by its neighbours ...

Soon the country's history culture and language were extinguished and its very name abolished. In this way was the white eagle of Poland devoured

by the three black eagles of Prussia, Russia, and Austria. ... Meanwhile the Poles looked for

France, with its revolutionary ideas of Liberty,

Equality and Fraternity, as a beacon of hope. The fact France's enemies happened to be Poland's

oppressors was an obvious attraction, and many Polish soldiers volunteered for service in the

French army." (Summerville - "Napoleon's Polish Gamble" p 15)

Marshal Murat entered Warsaw to a rapturous welcome.

He was feted by the Poles igniting vain hopes of future kingship.

"In the 16th century Poland had been one of the most powerful countries in Europe ...

within the space of 200 years, however, Poland had been eclipsed by its neighbours ...

Soon the country's history culture and language were extinguished and its very name abolished. In this way was the white eagle of Poland devoured

by the three black eagles of Prussia, Russia, and Austria. ... Meanwhile the Poles looked for

France, with its revolutionary ideas of Liberty,

Equality and Fraternity, as a beacon of hope. The fact France's enemies happened to be Poland's

oppressors was an obvious attraction, and many Polish soldiers volunteered for service in the

French army." (Summerville - "Napoleon's Polish Gamble" p 15)

To the Polish deputations which approached him in Berlin and at Warsaw, he replied vaguely,

"France has never recognised the different partitions of Poland; nevertheless, I

cannot proclaim your independence until you have decided to defend your rights as a

nation with arms in your hands by every sort of sacrifice, even that of life. You have

been reproached with having, in your continued civil dissensions, lost sight of the

interests of your country. Instructed by your misfortunes, reunite yourselves and prove to

the world that one spirit animates the whole Polish nation."

Napoleon was furious with Marshal Murat, for forwarding one petition from Warsaw, in which

it was prayed that the Polish kingdom might be reconstituted under a French commander.

Napoleon's replies to Poles were sufficiently encouraging to assure to him the moral and

material support of the Poles in the ensuing campaign, and to deprive Prussia and Russia

of all hope of recruiting their armies by voluntary enlistment in Poland.

Napoleon entered Warsaw in 1807 and French eagles soared over the Vistula. The Emperor

was hesitant about reenacting the Kingdom of Poland. In spite of the ovations given him

by the Poles, he wrote: "Only God can arbitrate this vast political problem ... It would

mean blood, more blood, and srtill more blood ..."

Napoleon entered Warsaw in 1807 and French eagles soared over the Vistula. The Emperor

was hesitant about reenacting the Kingdom of Poland. In spite of the ovations given him

by the Poles, he wrote: "Only God can arbitrate this vast political problem ... It would

mean blood, more blood, and srtill more blood ..."

But it was not long before

the Duchy of Warsaw became a bastion of France in central and Eastern Europe,

and Polish troops stood ready to fight for Napoleon and independence.

The war in 1807 was called by Napoleon the "First Polish War" and resulted

in the formation of the Polish state. The country was divided into departments.

The branches of justice, war, finance and police, were assigned to Polish government.

(In 1812 Napoleon, in an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and

patriots, termed the war against the Russian Empire the "Second Polish War.)

POPULATION of EUROPE (and USA).

Denmark - 1 million Denmark - 1 million

Saxony - 1,1 millions Saxony - 1,1 millions

Lombardy - 2 millions Lombardy - 2 millions

Papal State - 2,3 millions Papal State - 2,3 millions

Sweden - 2,3 millions Sweden - 2,3 millions

Portugal - 3 millions Portugal - 3 millions

Poland Duché de Varsovie - 4,3 millions Poland Duché de Varsovie - 4,3 millions

Naples - 5 millions Naples - 5 millions

USA - 6 millions USA - 6 millions

Holland & Belgium - 6,2 millions Holland & Belgium - 6,2 millions

Prussia - 9,7 millions (in 1806 reduced to 4,9 millions) Prussia - 9,7 millions (in 1806 reduced to 4,9 millions)

Spain - 11 millions Spain - 11 millions

Great Britain - 18,5 millions (England, Ireland, Scotland) Great Britain - 18,5 millions (England, Ireland, Scotland)

Austria - 21 millions (with Hungary) Austria - 21 millions (with Hungary)

France - 30 millions France - 30 millions

Russia - 40 (with annexed territories) Russia - 40 (with annexed territories)

Prince Poniatowski.

He was one of the few Napoleonic commanders

who was able to conduct a successful campaign

without Napoleon's supervision.

Poniatowski was the only foreigner

Napoleon promoted to marshal of France.

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski was born in 1763 and ten years

later became the ward of his uncle, the King of Poland. "Nicknamed 'the Polish Bayard',

Poniatowski was born in Vienna ... He was commisioned into the Austrian army in 1778,

serving in the dragoons and carabiniers, and in 1788 he became an ADC to the Emperor Francis II ..."

(Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic wars" p 346)

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski was born in 1763 and ten years

later became the ward of his uncle, the King of Poland. "Nicknamed 'the Polish Bayard',

Poniatowski was born in Vienna ... He was commisioned into the Austrian army in 1778,

serving in the dragoons and carabiniers, and in 1788 he became an ADC to the Emperor Francis II ..."

(Chandler - "Dictionary of the Napoleonic wars" p 346)

In 1788 he participated in the war against Ottoman Empire and

was wounded at siege of Sabatach. In 1789 Poniatowski returned to Poland, became general

and in 1792 won against the Russians at the Battle of Zielence. In July Poniatowski

resigned and left Poland but two years later the ardent patriot had returned and joined the

Kosciuszko Insurrection. After collapse of the uprising Poniatowski was in exile. When Poland

disappeared from the map of Europe, many Polish officers and generals fled to France where

they felt an ideological affinity. But not Poniatowski, in 1798 the restless soul was back

in the occupied by Prussians Warsaw.

In 1807 Poniatowski met Marshal Murat and French troops and began overtures to Napoleon

for the restoration of a free Poland. In 1807 he became minister of war in the Polish

Directory. In April 1809 Poniatowski selected a good defensive position at

Raszyn and withstood

all Austrian attacks. Then he defeated them at Radzymin and reconquered parts of former

Poland. Poniatowski routed the Austrians again at Góra and Grochów. For his achievements

Poniatowski was presented the French grand-aigle de la Légion d'Honneur and a saber of honor.

He was one of the few Napoleonic commanders who was able to conduct a successful campaign

without Napoleon's supervision.

In 1812 Poniatowski led the V Army Corps to Russia and fought at Smolensk, Borodino,

Tarutino and Krasne. In 1813 Poniatowski rebuilt the Polish troops that were to become the

VIII Army Corps. He led them to Saxony to join Napoleon's army.

Poniatowski's troops participated in several small engagements, was majority of them were

victories. At Leipzig Poniatowski's troops successfully defended Napoleon's flank for three

days. Napoleon promoted him to the rank of Marshal of France. On the last day of battle

some French troops and Poniatowski's Poles were covering the retreat of Napoleon's army.

When the bridge was destroyed Poniatowski spurred his horse into the Elster River.

Poniatowski was shot and disappeared under water. His body was found several days later.

Generals and Officers.

There was rivalry within the officers and generals between

those who had served in the army of the Duchy of Warsaw

and those who had joined Polish units in French service.

Polish officers and generals communicated in Polish and French language.

The troops were organized after the French model and used much of its terminology.

Chlapowski writes: "Our drill regulations were provided by General Dabrowski, translated from the French. Knowing the Prussian system, it was easy for me to learn these new regulations, which

were far simpler and much better suited to the conduct of war."

(Chlapowski/Simmons - p 13)

Polish officers and generals communicated in Polish and French language.

The troops were organized after the French model and used much of its terminology.

Chlapowski writes: "Our drill regulations were provided by General Dabrowski, translated from the French. Knowing the Prussian system, it was easy for me to learn these new regulations, which

were far simpler and much better suited to the conduct of war."

(Chlapowski/Simmons - p 13)

There was rivalry within the officers and generals between those who had served in the army

of the Duchy of Warsaw and those who had joined Polish units in French service.

The former often felt the latter had put self interest before patriotic duty,

while the latter scorned the former as military amateurs. The rivalry had been largely healthy, and

there had in fact been considerable interchange between the two.

General Fiszer (infantry, chief-of-staff)

Stanislaw Fiszer (1769-1812) - he came from a German family settled down in Poland.

(His father was Karl Fischer.) He entered military service in infantry and took part in

the wars against Russia. Fiszer ended up as Inspector-General of Infantry.

He had a tendency to imitate Poniatowski even in the manner of dress. Despite beign strict disciplinarian

this short man was loved by the soldiers but could be brusque with officers. Fiszer was

a superb organizer of infantry, his inspections were famous for their thoroughness.

He was one of the best Polish generals. On battlefield he was brave and decisive. Fiszer was killed in 1812 at Tarutino.

Stanislaw Fiszer (1769-1812) - he came from a German family settled down in Poland.

(His father was Karl Fischer.) He entered military service in infantry and took part in

the wars against Russia. Fiszer ended up as Inspector-General of Infantry.

He had a tendency to imitate Poniatowski even in the manner of dress. Despite beign strict disciplinarian

this short man was loved by the soldiers but could be brusque with officers. Fiszer was

a superb organizer of infantry, his inspections were famous for their thoroughness.

He was one of the best Polish generals. On battlefield he was brave and decisive. Fiszer was killed in 1812 at Tarutino.

General Rozniecki (cavalry)

Alexander Rozniecki - began career in the Polish Royal Guard, served in cavalry,

fought against the Russians and was engaged in patriotic conspiracies.

In 1807 was appointed Inspector-General of Cavalry. As general he was a gifted cavalry

organizer and brave commander. In 1809 Rozniecki led daring cavalry raids into Galicia,

in 1812 blundered at Mir and Romanow (against Cossacks) and rehabilitated himself at Borodino

against Russian cuirassiers and infantry). As a man he was rude to his subordinates and

servile toward his superiors. Zajaczeek called him "the greatest possible coward, a vile and abject intrigant."

Other contemporaries described him as being "dirty in soul and body, unkept in dress," "brutal, following his lust like a wild beast."

In combat not without personal courage, he was also a gifted cavalry organizer.

Alexander Rozniecki - began career in the Polish Royal Guard, served in cavalry,

fought against the Russians and was engaged in patriotic conspiracies.

In 1807 was appointed Inspector-General of Cavalry. As general he was a gifted cavalry

organizer and brave commander. In 1809 Rozniecki led daring cavalry raids into Galicia,

in 1812 blundered at Mir and Romanow (against Cossacks) and rehabilitated himself at Borodino

against Russian cuirassiers and infantry). As a man he was rude to his subordinates and

servile toward his superiors. Zajaczeek called him "the greatest possible coward, a vile and abject intrigant."

Other contemporaries described him as being "dirty in soul and body, unkept in dress," "brutal, following his lust like a wild beast."

In combat not without personal courage, he was also a gifted cavalry organizer.

General Axamitowski (artillery)

Wincenty Axamitowski (1760-1828) - began career in artillery, veteran of Italian campaigns,

organizer and commander of Polish artillery. Axamitowski was an enemy of Poniatowski and

ultra-loyal to Napoleon. He also served in the French army and was always quick to denounce

any anti-French activities among Polish officers. Very good soldier.

The Director of Artillery was a Frenchman, Colonel Pierre Bontemps.

The Inspector of Artillery and Engineers was another Frenchman Jean Baptiste Pelletier.

General Hauke (engineers)

Maurycy Hauke (1775-1830) - he was of German origin (Moritz von Haucke) and studdied artillery school in

Warsaw. Hauke entered military service as a miner in 1790.

Veteran of Italian campaigns, general in 1807, in 1809-1813 commander of

Zamosc fortress. The defense of fortress of Zamosc in 1813 is one of the most heroic episodes of this campaign.

Hauke was the most talented of Polish engineers during Napoleonic wars. In 1816 recognizing his abilities,

Tsar Nikolai appointed him Deputy Minister of War of Congress Poland (after Napoleonic wars Poland was under Russian occupation)

and elevated him to count.

Maurycy Hauke (1775-1830) - he was of German origin (Moritz von Haucke) and studdied artillery school in

Warsaw. Hauke entered military service as a miner in 1790.

Veteran of Italian campaigns, general in 1807, in 1809-1813 commander of

Zamosc fortress. The defense of fortress of Zamosc in 1813 is one of the most heroic episodes of this campaign.

Hauke was the most talented of Polish engineers during Napoleonic wars. In 1816 recognizing his abilities,

Tsar Nikolai appointed him Deputy Minister of War of Congress Poland (after Napoleonic wars Poland was under Russian occupation)

and elevated him to count.

The Director of Enginers was a Frenchman, Jean Baptiste Mallet.

General Sokolnicki (advance/rear guard)

Michal Sokolnicki (1760-1816) - studied in military academies in Warsaw and Saxony.

In 1809 he was one of the most enterprising commanders in the Austro-Polish war.

On battlefield he was a daring commander. For example in 1800 at Offenbach he led four companies

in a bayonet attack across a river. In 1809 at

Raszyn he gallantly defended his positions against superior enemy. He also defeated Austrians

at Grochów, Ostrówkiem, and at Sandomierz where he also took the fortress.

In 1812 Sokolnicki was French army's intelligence chief.

Michal Sokolnicki (1760-1816) - studied in military academies in Warsaw and Saxony.

In 1809 he was one of the most enterprising commanders in the Austro-Polish war.

On battlefield he was a daring commander. For example in 1800 at Offenbach he led four companies

in a bayonet attack across a river. In 1809 at

Raszyn he gallantly defended his positions against superior enemy. He also defeated Austrians

at Grochów, Ostrówkiem, and at Sandomierz where he also took the fortress.

In 1812 Sokolnicki was French army's intelligence chief.

He advised Napoleon to sent Polish troops not on Moscow but on Ukraine, where were some chances for pro-Polish and anti-Russian rebellion.

He also suggested not rushing on Moscow but to advance at slower pace, set winter camps and

continue the campaign in the next year. He thought that having thousands of warm uniforms

stored in depots even before the campaign started was a must.

In 1813 Sokolnicki distinguished himself as cavalry

commander at Leipzig

where his uhlans fought against vastly superior number of Austrian and Russian cuirassiers.

It was a masterpiece of cavalry combat where five regiments tamed nine.

As a man he was a very ambitious officer, and an opportunist suffering from self-importance.

~ Divisional Commanders (1808-1814) ~

(source: Nafziger, Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons ...")

General of Division

Jan-Henryk Dabrowski

1806: Posen Legion (Division)

1807: 3rd (Legion) Division

1810: II Military District

1812: 17th Infantry Division

1813: 27th Infantry Division |

General of Division

Karol Kniaziewicz

1812: 18th Infantry Division

1813: requested and received

dismissal from active service

. |

General of Division

Jozef Zajaczek

1806: Kalisz Legion (Division)

1807: 2nd (Legion) Division

1810: I Military District

1812: 16th Infantry Division

- he was taken prisoner by the Russians |

| He was born in Poland, and educated in Saxony.

In 1769-1792 served in the Saxon Guard Cavalry, in 1792 returned to

Poland and served in the Polish army. In 1794 he joined Kosciuszko

Insurection, and led his small corps into Great Poland to hinder for 6 weeks the advance of 30,000 Prussians.

In 1796 joined the French army and was nominated general de division,

1797 - commander of Polish forces in Italy, 1807 - Inspector General of Cavalry of the Italian Republic,

1806 - recalled from the Italian service to organize the new Polish army.

A marching song mentioning his name along with that of Bonaparte - the "Dabrawski's Mazurek" of 1797 -

in time became the Polish national anthem.

"A bear of a man, good natured and rather phlegmatic.

A great patriot ... Contemporaries sometimes criticized him for his too-lenient

attitude toward captured German officers ... An excellent organizer, a well-educated

and very capable officer, a brave soldier and caring leader of men. Military historians

sometimes blame him for abandoning the bridge at Borisov, not remembering that he put up

a stubborn resistance, losing 1,800 of his 2,400 Poles."

|

He was born and educated in Poland. Although he commanded a division only once, Kniaziewicz was

one of the most important military figures in the Polish army.

In 1797 arrived in Italy and joined Dabrowski's Legions.

Captured the fortress of Gaete. In 1799 became general de brigade and was appointed commander of the Danube Legion.

In 1800 istinguished himself at Hohenlinden. Dissatisfied with Bonaparte's Polish policy, resigned

his command. In 1807 rejected Tsar Alexander's offer to organize Polish troops in the Russian service.

. .

"More a knight than a commanding general. A giant endowed with

proportionate strength (he could easily break a horseshoe in two); a man of absolute integrity and courage, critical toward Napoleon.

An uncompromising patriot. Kept away from personal feuds.

An excellent soldier, officer and commander, but motivated more by his sense of honor than by

any political calculations."

|

He was the most colorful figure among the divisional commanders and the most tragic.

He began his carrer in Polish cavalry and became captain. In 1777 was with the Russian army during the

Russo-Turkish war. In 1784 lieutenant-colonel in Polish army, in 1792 colonel, then general.

In 1796 with the French army, attached to the general staff in Italy. In 1798-1801

helped preparing the Egyptian Expedition. Fought in Egypt, in May 1801 was appointed general commander of cavalry in

the Armee d'Egypte. In 1801-805 was back in Italy, in 1806 in Poland with the French.

In Sept he was appointed organizer and commander of the (1st) Legion du Nord.

In 1807 was unwillingly transferred to the Polish army.

"A man of innumerable contradictions, a firebrand and born plotter, but not much of

typical and born opportunist. .... His choleric temperament and sharp tongue didn't gain him many friends.

Self-rightous and individualistic to the extreme, he quarelled both with Poniatowski and Dabrowski.

A good leader and organizer with great personal courage. An exacting and demanding commander, he was quite unpopular in

the officer corps.

|

1806-1808

The whole [Polish] army was learning and its excellent spirit,

liveliness and cheerful confidence bade well for the future."

- Officer Chlapowski

In the years 1806-1807 Napoleon defeated Austria, Prussia and Russia. Under the Treaty of

Tilsit the Duchy of Warsaw was established on part of the lands of Prussian-annexed Poland.

It was placed under the guardianship of the King of Saxony. The constitution given by

Napoleon in July 1807 established the Polish army at 30,000 men. Prince Poniatowski became

its Minister of War. The Poles joked about the Duchy having "a Saxon king, French laws,

Polish army, and Prussian currency." (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons" p 3)

In the years 1806-1807 Napoleon defeated Austria, Prussia and Russia. Under the Treaty of

Tilsit the Duchy of Warsaw was established on part of the lands of Prussian-annexed Poland.

It was placed under the guardianship of the King of Saxony. The constitution given by

Napoleon in July 1807 established the Polish army at 30,000 men. Prince Poniatowski became

its Minister of War. The Poles joked about the Duchy having "a Saxon king, French laws,

Polish army, and Prussian currency." (Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons" p 3)

In November 1806 Napoleon directed General Dabrowski to form Polish troops.

Dabrowski issued a decree ordering the population to provide 1 infantry recruit from every

10 households, 1 cavalry recruit from every 45 households and 1 chasseur (light infantry)

recruit from every estate.

In January 1807 the Polish army consisted of 20.500 recruits

and approx. 3.000 volunteers. The army was organized into three legions (divisions).

In August Marshal Davout selected the best infantry regiment of every division

and Napoleon took these units to Spain. "Napoleon took this force into French service on

much the same basis as the Hessians served the British in the American Revolution."

(Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons" p 12)

The chosen troops were: 4th, 7th and 9th Infantry Regiment, 140-men artillery company and

200-man sapper company. Several battalions were sent to Prussia. Due to such wide

distribution of Polish troops the divisional organization had become obsolete.

In the end of 1807 the army consisted of:

12 infantry regiments

6 cavalry regiments

3 battalions of artillery.

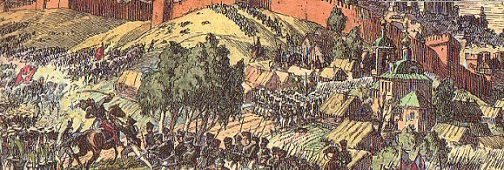

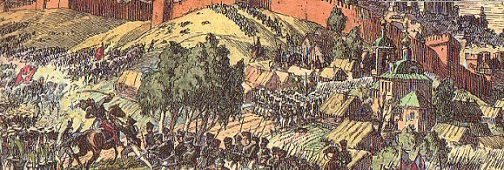

The Polish troops participated in the campaign of 1807.

On 27th January 1807 they fought at Tczew (Dirschau), on 14th February they took Gniew (Mewe)

and on 20th captured Slupsk (Stolpen). On 23rd February they took Tczew (Dirschau).

Napoleon awarded GdD Dabrowski with cross of the Legion d'Honneur.

In March-May 9.000 Polish troops (attached to French divisions) participated in

the siege of Gdansk (Danzig). The Poles suffered approx. 2.000 killed and wounded.

The Poles also participated in the Battle of Friedland.

The Polish troops participated in the campaign of 1807.

On 27th January 1807 they fought at Tczew (Dirschau), on 14th February they took Gniew (Mewe)

and on 20th captured Slupsk (Stolpen). On 23rd February they took Tczew (Dirschau).

Napoleon awarded GdD Dabrowski with cross of the Legion d'Honneur.

In March-May 9.000 Polish troops (attached to French divisions) participated in

the siege of Gdansk (Danzig). The Poles suffered approx. 2.000 killed and wounded.

The Poles also participated in the Battle of Friedland.

In February 1808 the Polish Legion du Nord was incorporated into the Polish army.

In November 1808, Napoleon was in Spain, marching on Madrid. His advance was blocked by Spanish troops.

The Spaniards held the narrow defile of Somosierra, leading on to the lofty plateau where Madrid stands.

Sixteen guns were holding off Napoleon's army. After repeated attempts to force the position

with infantry, the regiment of Polish lighthorsemen were given the order to charge. Approx. 200 men obeyed and eight minutes later, the survivors emerged from the top

of the hill, "a thousand feet and three miles above the admiring Emperor."

(- Norman Davies p. 301)

All the cannons were taken and enemy's resistance was broken.

In later years, talk of the charge of Somosierra evoked the same reactions in Warsaw as

mention of the charge of the Light Brigade in London. The flower of the nation's youth was thought

to have perished in a distant land for the sake of a courageous gesture. In fact, the exemplary sacrifice of those few men ensured the passage

of a whole army.

The Polish forces of that period were in excellent state. Officer Chlapowski writes: "It was marvelous to be back in Warsaw. ... there was a great difference

between these new regiments and the Polish Guard and Vistula Legion

with which I had recently been in Spain. As well as Colonel Krasinski, the entire staff of the Polish Guard Lighthorse were experienced officers ...

The Vistula Legion still had officers from Dabrowski's Italian Legion and even Kniaziewicz's Legion of the Rhine. Nearly all the NCOs were older men, so training was steady, severe,

and regular. It wasn't like that in the army of the Duchy of Warsaw. The infantry was admittedly first class, but the cavalry still needed a lot of work.

... The artillery had only very few qualified officers, but the gunners were quite well trained.

The whole army was learning and its excellent spirit, liveliness and cheerful confidence bade well

for the future."

1809 Campaign.

Poniatowski fought to a standstill

an Austrian force more than twice the size.

In the campaign of 1809, the Duchy of Warsaw sustained the full weight of the Austrian attack.

Austrian corps under Archduke Ferdinand appeared on the Polish borders on April 14, 1809.

Taken by surprise, the Polish government ordered general mobilization. Headed by Prince

Poniatowski the few Polish troops offered an valiant resistance during the

Battle of Raszyn.

Poniatowski fought to a standstill an Austrian force more than twice the size.

But it was necessary to abandon Warsaw and to withdraw to the right bank of the Vistula.

In the campaign of 1809, the Duchy of Warsaw sustained the full weight of the Austrian attack.

Austrian corps under Archduke Ferdinand appeared on the Polish borders on April 14, 1809.

Taken by surprise, the Polish government ordered general mobilization. Headed by Prince

Poniatowski the few Polish troops offered an valiant resistance during the

Battle of Raszyn.

Poniatowski fought to a standstill an Austrian force more than twice the size.

But it was necessary to abandon Warsaw and to withdraw to the right bank of the Vistula.

All Austrian efforts to cross the Vistula River were in vain. While the Austrians

were exhausting themselves in their attempts to get at the right bank of the Vistula,

Poniatowski crossed the Austrian frontier to liberate Galicia. On May 14 the city of Lublin

was taken and on the 18th the city of Sandomierz with its only major Vistula bridge.

On the 20th, in a night attack, the Zamosc fortress was captured together with 2,000

prisoners and 40 cannons. These developments compelled the Austrians to withdraw from

Warsaw. Everywhere enthusiastically received by the Poles, Poniatowski was able to liberate

large areas of Galicia.

"For the first time since the partitions a Polish army had taken to the field under Polish

command and had succeeded in reuniting two important pieces of the shattered Polish lands.

National sentiment revived. Hopes were raised anew.

Poles from Lithuania swam across the Niemen river to escape from Russia and serve in the

Duchy's army. Poles from the Prussian and Austrian partitions came over to swell the ranks:

and all were offereed citizenship in the Duchy's service."

(- Norman Davies, p 302)

As a result of Polish offensive, and of the fact that Poniatowski had Polish administration

and military structure in place there for some time, making it difficult for Napoleon to

compromise the Polish gains for political expediency. Most of the liberated lands became

incorporated into the Grand Duchy in October 1809.

After the victorious war against Austria and annexation of Galicia the Poles raised 6 new

infantry regiments and 10 cavalry regiments (1 cuirassiers, 2 hussars and 7 uhlans).

After the victorious war against Austria and annexation of Galicia the Poles raised 6 new

infantry regiments and 10 cavalry regiments (1 cuirassiers, 2 hussars and 7 uhlans).

Strength of the Polish army in the end of 1809:

18 infantry regiments (with depots) - 45.000 men

16 cavalry regiments (with depots) - 14.500 men

artillery and sapers (with depots) - 2.620 men

Vistula Legion and Guard lancers (with depots) - 7.000 men

Part of the army served in France, Germany and Spain under French and Polish generals.

Polish Army in January 1809

| Infantry |

Cavalry |

Artillery and Engineers |

1st Infantry Regiment (1.707 men)

2nd Infantry Regiment (1.707 men)

3rd Infantry Regiment (1.707 men)

4th Infantry Regiment (1.808 men)

5th Infantry Regiment (1.933 men)

6th Infantry Regiment (1.635 men)

7th Infantry Regiment (1.817 men)

8th Infantry Regiment (1.539 men)

9th Infantry Regiment (1.945 men)

10th Infantry Regiment (???? men)

11th Infantry Regiment (???? men)

12th Infantry Regiment (1.178 men)

FIRST VISTULA LEGION

1st Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

2nd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

3rd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

SECOND VISTULA LEGION

(It never was able to form completely,

so it was disbanded in 1810 and

incorporated into the First Legion

as a 4th Inf. Reg. of Vistula Legion)

|

1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (745 men)

2nd Uhlan Regiment (880 men)

3rd Uhlan Regiment (719 men)

4th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (??? men)

5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (596 men)

6th Uhlan Regiment (691 men)

Uhlan Regiment of Vistula Legion

Chevaulegere Regiment of Napoleon's Guard

.

.

.

.

.

|

I Battalion of Foot Artillery (409 men, 24 guns)

II Battalion of Foot Artillery (137 men, 24 guns)

III Battalion of Foot Artillery (266 men, 24 guns)

Train Battalion of Foot Artillery (402 men)

I Squadron of Horse Artillery (119 men, 6 guns)

Train Squadron of Horse Artillery (119 men)

1st Sapper Company (79 men)

2nd Sapper Company (103 men)

3rd Sapper Company (91 men)

Pontoneer Company (67 men)

.

.

.

.

.

|

Polish Army in November-December 1809

| Infantry |

Cavalry |

Artillery and Engineers |

1st Infantry Regiment

2nd Infantry Regiment

3rd Infantry Regiment

4th Infantry Regiment

5th Infantry Regiment

6th Infantry Regiment

7th Infantry Regiment

8th Infantry Regiment

9th Infantry Regiment

10th Infantry Regiment

11th Infantry Regiment

12th Infantry Regiment

13th Infantry Regiment

14th Infantry Regiment

15th Infantry Regiment

16th Infantry Regiment

17th Infantry Regiment

18th Infantry Regiment

FIRST VISTULA LEGION

1st Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

2nd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

3rd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

SECOND VISTULA LEGION

(It never was able to form completely,

so it was disbanded in 1810 and

incorporated into the First Legion

as a 4th Inf. Reg. of Vistula Legion)

|

1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment

2nd Uhlan Regiment

3rd Uhlan Regiment

4th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment

5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment

6th Uhlan Regiment

7th Uhlan Regiment

8th Uhlan Regiment

9th Uhlan Regiment

10th Hussar Regiment

11th Uhlan Regiment

12th Uhlan Regiment

13th Hussar Regiment

14th Cuirassier Regiment

15th Uhlan Regiment

16th Uhlan Regiment

Uhlan Regiment of Vistula Legion

Chevaulegere Regiment of Napoleon's Guard

.

.

.

.

|

I Battalion of Foot Artillery

II Battalion of Foot Artillery

III Battalion of Foot Artillery

Train Battalion of Foot Artillery

I Squadron of Horse Artillery

Train Squadron of Horse Artillery

1st Sapper Company

2nd Sapper Company

3rd Sapper Company

Pontoneer Company

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

|

1812 - Invasion of Russia.

The Poles formed the largest of the contingents

provided by any of the states allied with France.

The Poles stood by Napoleon through thick and thin.

They formed a striking contrast to the Prussians, who as soon as

Napoleon's defeat became known joined the Russians,

as did also the Austrians.

The year of 1812 saw the climacteric of the Napoleonic era. For the French it was just another campaign, for the Russians it presented

the supreme test for the integrity and durability of their mighty empire.

For the Poles alone, it was a war of liberation.

The year of 1812 saw the climacteric of the Napoleonic era. For the French it was just another campaign, for the Russians it presented

the supreme test for the integrity and durability of their mighty empire.

For the Poles alone, it was a war of liberation.

In early 1812 due to financial difficulties in the Grand Duchy, Napoleon took into French

pay several units: artillery companies in the fortresses of Gdansk (Danzig) and Kostrzyn

(Kustrin), the 9th Uhlan Regiment, 5th, 10th and 11th Infantry Regeiment. Napoleon approved

Poniatowski's suggestion to add 2 light cannons to every Polish infantry regiment. The

strength of companies in infantry and cavalry regiments was increased.

Before the campaign against Russia the army of the Grand Duchy consisted of more than

75.000 men and 165 guns.

22 infantry regiments (3 field and 1 depot battalion each)

20 cavalry regiments (4 field and 1 depot squadron each)

1 foot and 1 horse artillery regiment

Vistula Legion and Guard lancers

Minister of War - Prince Jozef Poniatowski

. . . Secretary General - Col. Jean Bennet (Frenchman)

. . . . . . . . . 1st Section of Finances - Fechner

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Section of Military Operations - Col. Rautenstrauch

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Section of Artillery and Engineers - Col. Redel

General Directorate of Administration of War - GD Wielhorski.

. . . Secretary General - Wilkoszewski

. . . . . . . . . 1st Section of Military Hospitals - Doney

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Section of Uniforms - J. Suchodolski

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Section of Supplies and Forage - Deybell

. . . Health Services - L. Lafontaine (Frenchman)

. . . . . . . . . Inspector of Military Hospitals - Puchalski

. . . Inspector of Military Reviews and Conscription - GB Hebdowski

. . . . . . . . . Chief of the Office of Management of Reviews - Wyszkowski

. . . . . . . . . Inspectors of Reviews in Poland - Miroslawski, Kasinowski, and Hryniewicz

. . . . . . . . . Inspector of Reviews in Lithuania - Sarnowski

. . . Military Paymaster - J. Wegierski

Commander-in-Chief of the Army Prince Jozef Poniatowski

. . . . . . . . . Command Adjutant Assistant Chief-of-General Staff - Col. Rautenstrauch

. . . . . . . . . Adjutant Colonel Attached to the Commander-in-Chief - A. Potocki

Chief-of-Staff - GD Fiszer

. . . Inspector General of Infantry - GD Fiszer

. . . Inspector General of Cavalry - GD Rozniecki

. . . Inspector General of Artillery and Engineers - GB Pelletier (Frenchman)

One of the causes of the war of 1812 was the existence of the Duchy.

In spite of Napoleon's continuous assurances that "the dangerous Polish dreams" as Alexander

called them, would never be permitted realization, the Russian monarch was forever restive.

He demanded that the word "Poles" be not used in public documents, that Polish orders be

abolished and that the Polish army be considered as a part of that of Saxony.

Meanwhile, the "second Polish war," as Napoleon called it, broke out.

According to Adam Zamojski Napoleon was determined to hold the possibility of the

reunification of the Kingdom of Poland as a carrot before the Poles,

a semi-sincere promise to ensure loyalty. He avoided any concessions toward Poland having in mind further

negotations with Russia. Poniatowski talked with Napoleon about forming the Kingdom of Poland

and thus mobilizing the entire country. "Poniatowski has had to appeal to Davout to put in a word

on his behalf. And now standing there by the roadside as Colbert's lancers again file by, he's urging

Napoleon to mobilize Poland and thus consolidate the army's rear, instead of marching on Moscow. But the

Polish prince, who'd turned down the Tsar's handsome offers of advancement if he had side with him,

gets nowehere. Napoleon simply tells him he doesn't matters of high policy."

(Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 173)

In June of 1812, Poniatowski together with 100,000 of his fellow Poles were part of Napoleon's

expedition. The Poles formed the largest of the contingents provided by any of the

states allied with France. The dispersion, however, of the Polish regiments among the

various French corps was strongly resented.

For nowhere else had Napoleon a more loyal and devoted ally than the Poles who stood by him through thick and

thin. They formed a striking contrast to the Prussians under Yorck, who as soon as

Napoleon's defeat became known joined the Russians, as did also the Austrians.

The war began when the napoleonic troops crossed the border with Russia.

"At the sight of this crossing, a group of Polish uhlans, probably belonging to the 6th Uhlans, spurred their mounts froward

into the river, hoping to seize the honor of being the first to be on Russian soil. Unfortunately, the current proved too swift

and they were quickly swept downstream, engulfed by the river. As the men slipped beneath its waters they were clearly

heard to cry, 'Vive l'Empereur !' (Nafziger - "Napoleon's Invasion of Russia" pp 114-5, 1998)

In 1812 the Polish troops carried the fame of Polish heroism along the same roads which two and three centuries before, in the times of King

Stefan Batory and King Wladyslav IV saw the Polish banners of the White Eagle in a triumphant

march to Moscow. The memories of Hetman Zolkiewski and Gosiewski came back.

At Czerepowo General Rozniecki "orders the Polish troops to halt, forms up in square and reminds us that we're standing at the limit of the Jagellons'

and Batory's one-time empire. After painting for us the heroic aspects of our nation's glorious past he invites all present

to dismount and pick up a little dust so as to be able to remind our descendants of this glorious event which has brought us back to Poland's

former linits." (Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 234)

The Poles fight with a great zeal.

Britten-Austin writes: "Some units, perhaps many, are mortified to find their exploits

have escaped official notice. To his left had seen the 7th Hussars make a brilliant

charge against

Russian ainfantry and cavalry, and only lose a few men in so doing. 'A short way away

to our left,' writes Dupuy

'the 9th Polish Lancers [Uhlans ?] pierced a square of Muscovite chasseurs and wiped it out.' To Thirion it had seemed 'these men

[Poles] had become fighting mad. How many didn't I see who, with arm or leg bandaged, returned to the scrum at a flat-out gallop,

forcefully eluding those of their comrades who tried to hold them back."

(Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 136)

The Poles fight with a great zeal.

Britten-Austin writes: "Some units, perhaps many, are mortified to find their exploits

have escaped official notice. To his left had seen the 7th Hussars make a brilliant

charge against

Russian ainfantry and cavalry, and only lose a few men in so doing. 'A short way away

to our left,' writes Dupuy

'the 9th Polish Lancers [Uhlans ?] pierced a square of Muscovite chasseurs and wiped it out.' To Thirion it had seemed 'these men

[Poles] had become fighting mad. How many didn't I see who, with arm or leg bandaged, returned to the scrum at a flat-out gallop,

forcefully eluding those of their comrades who tried to hold them back."

(Britten-Austin - "1812 The March on Moscow" p 136)

The initial period of the offensive was wasted, because

Poniatowski was placed under the direction of Napoleon's incompetent brother Jerome, who

criticized by Napoleon eventually left, but for Poniatowski, then put in charge of Grande

Armee's right wing, it was too late to make up for the lost opportunities (Later on St. Helena,

the dethroned emperor reflected back on the 1812 war with Russia and expressed his belief,

that if he had given Poniatowski Jerome's right wing command from the beginning, Bagration's

army would have been destroyed early, and the campaign would have followed a different course.

The Poles fought hard in every major battle of the campaign, including Smolensk, Borodino and Berezina.

In the very end of 1812 the Polish forces consisted of less than 10.000 men.

The splendid Vistula Legion had only 500 survivors. The campaign ended in a disaster.

William Napier writes: "Napoleon, unconquered of man, had been vanquished by the elements. The fires and the snows of

Moscow combined had shattered his strength, and in confessed madness nations and rulers rejoiced that an enterprise, at once the grandest and most provident,

the most beneficial ever attempted by a warrior-statement, had been foiled - they rejoiced

that Napoleon had failed to reestablish unhappy Poland as a barrier against the most

formidable and brutal, the most swinish tyranny that has ever menaced and disgraced European civilization."

(Napier - Vol IV, p 167)

|

Polish troops in August 1812 in Russia

V Army Corps - GdD Prince Jozef Poniatowski

Chief-of-Staff: GdD Fiszer

Chief-of-Artillery: GdB Pelletier [Frenchman]

Chief-of-Staff of Artillery: Col. Jakub Redel

16th Infantry Division - GdD Zajaczek

Infantry Brigade - GdB Mielzynski

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Infantry Regiment (2.621 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 15th Infantry Regiment (2.675 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

Infantry Brigade - GdB Paszkowski

. . . . . . . . . 13th Infantry Regiment (2.371 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 16th Infantry Regiment (2.679 men,2 3pdr cannons)

Divisional Artillery - Chef ?

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Foot Battery (144 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . 12th Foot Battery (159 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Sapper Company (72 men)

17th Infantry Division - GdD Dabrowski

Infantry Brigade - GdB Zoltowski

. . . . . . . . . 1st Infantry Regiment (2.396 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 6th Infantry Regiment (2.543 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

Infantry Brigade - GdB Krasinski

. . . . . . . . . 14th Infantry Regiment (2.544 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 17th Infantry Regiment (2.666 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

Divisional Artillery - Chef Gugenmus

. . . . . . . . . 10th Foot Battery (167 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . 11th Foot Battery (175 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Sapper Company (71 men)

18th Infantry Division - GdD Kniaziewicz

Infantry Brigade - GdB Grabowski

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Infantry Regiment (2.420 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 8th Infantry Regiment (2.422 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

Infantry Brigade - GdB Pakosz

. . . . . . . . . 12th Infantry Regiment (2.206 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . This infantry regiment was detached

Divisional Artillery - Chef ?

. . . . . . . . . 4th Foot Battery (163 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . 5th Foot Battery (153 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Sapper Company (61 men)

Light Cavalry Division - GdD Kaminski then Sebastiani, Lefebvre-Desnouettes

18th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB ?

. . . . . . . . . 4th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (786 men in 4 squadrons)

19th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB ?

. . . . . . . . . 1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (652 men)

. . . . . . . . . 12th Uhlan Regiment (497 men)

19th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB ?

. . . . . . . . . 5th Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment (791 men in 4 sq.)

. . . . . . . . . 13th Hussar Regiment (755 men in 4 sq.)

Corps Reserve Artillery - Col. Gorski

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Horse Battery (152 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . 14th Foot Battery (158 men, 6 12pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . Pontoneers (121 men, bridging equipment)

General Artillery Park

. . . . . . . . . 7th Foot Battery (169 men, no guns)

. . . . . . . . . 8th Foot Battery (81 men, no guns)

. . . . . . . . . 9th Foot Battery (86 men, no guns)

. . . . . . . . . 13th Foot Battery (75 men, no guns)

. . . . . . . . . 15th Foot Battery (89 men, no guns)

IV Cavalry Corps - GdD Latour-Maubourg

Corps Artillery - Chef Szwerin

. . . . . . . . . Polish 3rd Horse Battery (168 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Polish 4th Horse Battery (167 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Saxon Horse Battery (176 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Westphalian Horse Battery (69 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

4th Light Cavalry Division - GdD Rozniecki

28th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Dziewanowski

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Uhlan Regiment (596 men in 3 squadrons)

. . . . . . . . . 7th Uhlan Regiment (672 men)

. . . . . . . . . 11th Uhlan Regiment (551 men)

29th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Turno

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Uhlan Regiment (658 men)

. . . . . . . . . 11th Uhlan Regiment (688 men)

. . . . . . . . . 16th Uhlan Regiment (728 men)

7th Heavy Cavalry Division - GdD Lorge

1st Brigade - GdB Thielemann

. . . . . . . . . Polish 14th Cuirassier Regiment (300 men ?)

. . . . . . . . . Saxon 'Zastrow' Cuirassier Regiment (4 sq.)

. . . . . . . . . Saxon Garde du Corps Regiment (4 sq.

2nd Brigade - GdB Lepel

. . . . . . . . . Westphalian 1st Cuirassier Regiment

. . . . . . . . . Westphalian 2nd Cuirassier Regiment

28th Infantry Division - GdD Girard

Infantry Brigade - GdB Ouviller

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Infantry Regiment (1.331 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 7th Infantry Regiment (967 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

. . . . . . . . . 9th Infantry Regiment (1.281 men, 2 3pdr cannons)

Infantry Brigade - GM Klengel

. . . . . . . . . Saxon "Von Low" Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . Saxon "Von Rechten" Infantry Regiment

Divisional Artillery - Chef ?

. . . . . . . . . 1st Foot Battery (67 men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Foot Battery (?? men, 4 6pdr cannons, 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Sapper Company (97 men)

Infantry Division of Vistula Legion - GdD Claparede

Chief-of-Staff: Colonel Briatte

1st Infantry Brigade - GdB Chlopicki

. . . . . . . . . 1st Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

2nd Infantry Brigade - GdB Bronikowski

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

. . . . . . . . . 4th Infantry Regiment of Vistula Legion

Divisional Artillery .

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 cannons and 2 howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 cannons and 2 howitzers)

in the Imperial Guard:

4th Guard Cavalry Brigade - GdB Krasinski

Chevaulegere-Lanciers de la Garde Imperiale - GdB Konopka

. . . . . . . . . I Squadron - Kozietulski

. . . . . . . . . II Squadron - Chlapowski

. . . . . . . . . III Squadron - Jerzmanowski

. . . . . . . . . IV Squadron - Krasinski

. . . . . . . . . V Squadron - Fredro

. . . . . . . . . company of Vistula Uhlans

|

.

1813 - Campaign in Germany

Though the ranks of Poniatowski's troops were thinned,

their determination was strong.

"The last act of independent will was carried out in the Duchy's behalf by Jozef Poniatowski.

Refusing offers of clemency from the Russians, he determined to fight to the last at

Napoleon's side. He gathered the reserves of his army together and retreated into Germany."

(- Davies, Vol II, p 304)

"The last act of independent will was carried out in the Duchy's behalf by Jozef Poniatowski.

Refusing offers of clemency from the Russians, he determined to fight to the last at

Napoleon's side. He gathered the reserves of his army together and retreated into Germany."

(- Davies, Vol II, p 304)

Poniatowski began withdrawing across Poland "as Schwarzenberg's perfidious

maneuvers exposed him to the approaching Russians. His 8.000 army was joined by about

6.000 light cavalry..." (Nafziger and Wesolowski - "Poles and Saxons of the

Napoleonic Wars" p 22)

In July, few months before the battle of Leipzig was fought, Polish infantry and artillery had

allowance for exercises in life fire training and shooting competitions. According to Mariusz

Lukasiewicz's "Armia Ksiecia Jozefa" (p 215) the best shooters were awarded with 20

francs each. Captain Baka worked very hard to train the hundreds of young recruits

in the 'Krakus' (pronounced: crack-coos) Regiment. It was a new unit and mounted on small

horses. Fighting the feared Cossacks became Krakusi's specialty.

Napoleon called them "Pygmy cavalry", others called them "Polish Cossacks" this is because

of their horsemanship and tactics. The Krakusi had simpler maneuvers and orders but all movements had to be done in great speed.

It was probably the only one regiment in entire Napoleonic army which captured Cossack Color.

The Empreror expressed his wish to have 3.000 of them.

Near Zittau in Saxony Prince Poniatowski ordered intensive and large scale "war games"

for his troops. The quarters were excellent and the food was pretty good.

Many soldiers received new uniforms, shoes, shirts, and headwears.

Morale of the troops was very high despite of lack of weapons. According to General

Sokolnicki only 20 % of men in IV Cavalry Corps had carbines. The average cavalryman was armed with

lance, saber and one pistol.

In May 1813 Napoleon formed so-called Grenadier Corps, which became part of the French

Imperial Guard. It consisted of three battalions (each of 4 companies); the 1st Battalion of Poles, 2nd of Saxons and 3rd of Westphalians.

It was Napoleon's attempt to establish closer ties to the Poles and Germans.

The grenadiers were selected by Prince Poniatowski from the infantry of VIII Army Corps.

They were brave men, at least 23-years old and with 2 years' service.

|

~ Polish troops in Leipzig, in October 1813 ~

VIII Army Corps - GdD (MdE) Prince Jozef Poniatowski

Chief-of-Staff: GdD Aleksander Rozniecki

Chief-of-Artillery: Col. Jakub Antoni Redel

Chief-of-Engineers: Col. Jean C. Mallet [Frenchamn]

Advance Guard of VIII Army Corps - GdB Jan Nepomucen Uminski

. . . . . . . . . Krakus Cavalry Regiment (4 squadrons)

. . . . . . . . . 14th Cuirassier Regiment (1-2 squadrons, no armor)

26th Infantry Division - GdD Ludwik Kamieniecki

1st Infantry Brigade - GdB Jan Kanty Julian Sierawski

. . . . . . . . . Vistula Legion Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 1st Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 16th Infantry Regiment

2nd Infantry Brigade - GdB Kazimierz Malachowski

. . . . . . . . . 8th Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 15th Infantry Regiment

Divisional Artillery - Cpt. Franciszek Orlinski.

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

27th Infantry Division - GdD Jan Henryk Dabrowski

1st Infantry Brigade - GdB Edward Zoltowski

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 4th Infantry Regiment

2nd Infantry Brigade - GdB Stefan Grabowski

. . . . . . . . . 12th Infantry Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 14th Infantry Regiment

Divisional Artillery -

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Horse Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

Corps Reserve Artillery - Col. Pierre-Charles-Francois Bontemps

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery

. . . . . . . . . Foot Battery

. . . . . . . . . Sapper Company

IV Cavalry Corps - GdD Michal Sokolnicki

Chief-of-Staff: GdB Charles Antoine Benoist de Tancarville ?

7th Light Cavalry Division - GdD ....

17th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Jozef Tolinski

. . . . . . . . . 1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 3rd Uhlan Regiment

18th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Jan Krukowiecki

. . . . . . . . . 2nd Uhlan Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 4th Uhlan Regiment

Divisional Artillery - Capitaine Schwerin

. . . . . . . . . Horse Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

8th Light Cavalry Division - GdD Antoni Pawel Sulkowski

19th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Kazimierz Turno

. . . . . . . . . 6th Uhlan Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 8th Uhlan Regiment

20th Light Cavalry Brigade - GdB Jan Weyssenhoff

. . . . . . . . . 16th Uhlan Regiment

. . . . . . . . . 13th Hussar Regiment

Divisional Artillery - Cpt. Masson

. . . . . . . . . Horse Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

Corps Artillery:

. . . . . . . . . Horse Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

. . . . . . . . . Horse Battery (4 6pdr cannons and 2 5.5" howitzers)

|

.

1814 - Campaign in France.

When informed of the French surrender

the Vistula Regiment nearly mutined.

After Napoleon's defeat at Leipzig the majority of Polish soldiers were either killed,

wounded and taken prisoner, others wandered back to Poland. Only few followed

the French. Napoleon entertained thoughts of completely disbanding

Polish infantry and organizing four uhlan and two Polish-Cossack regiments.

(Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 28)

In December Napoleon formed so-called Polish Corps, it consisted of the following

troops (strength on 1st January 1814):

Krakusi Regiment

1st Uhlan Regiment (530 men + 399 horses)

2nd Uhlan Regiment (530 men + 336 horses)

Vistula Infantry Regiment (854 men in 2 battalions)

four companies of foot artillery (520 men)

company of horse artillery (125 men + 47 horses ONLY)

sapper company (68 men)

There were in France other Polish units, but all were cavalry:

4th, 8th and 16th Uhlan Regiment

1st Chasseur-a-Cheval Regiment

13th Hussar Regiment

3rd Eclaireur Regiment of the Guard

1st Lancer Regiment of the Old Guard

In 1814 officer Skarzynski overwhelmed and ridden down by a flood of Cossacks,

wrenched an "especially heavy" lance from one of them and - wild with the outraged

fury of despair - spurred amuck down the road, bashing every Cossack skull that

came within his reach. Rallying and wedging in behind him, his Polish handful

cleared the field. Impressed Napoleon made Skarzynski the Baron of the Empire.

The last stand of Polish troops took place in March 1814 at Soissons.

Soissons was defended by a very weak garrison: 792 men of Vistula infantry, 80 eclaireurs,

20 French

guns and 300 French municipal guardsmen. The overall command was in the hands of GdB Moreau.

Napoleon ordered him to hold his position at all costs. On 1st March numerous Prussian and

Russian troops arrived before Soissons. The next day they bombarded the town and stormed the

ramparts.

Approx. 300 men of Vistula Regiment "attacked them with such impetus that they were pushed

out of the suburb, far into the surrounding fields."

(Nafziger - "Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars" p 129)

In the evening an emissary arrived with a call to surrender. During a war council Moreau and the commander of Vistula

Regiment voted categorically against capitulation. Soon another emissary arrived with stronger worded ultimatum

threatening to put the garrison to the sword and sack the town.

Moreau agreed to capitulate.

When informed of this the Vistula Regiment nearly mutined. The Allies were in such a hurry

that at 3 pm two battalions entered the town and found themselves facing the angry Vistula

Regiment. The commander of the Poles told the allies general to leave for another hour

or he would start shooting !

The Allies general quickly agreed. At 4 pm the garrison departed Soissons with its weapons, receiving military honors.

Allies generals asked Moreau why he didn't order his division to march after the vanguard, Moreau replied that this was his entire force.

The Vistula Regiment was awarded by Napoleon with 23 crosses of Legion d'Honneur for its

actions at Soissons.

In Waterloo in 1815, there was only one single squadron of Poles.

They formed the 1st Squadron of the Red Lancers.

|

The lands of present day Poland were populated by many different Slavic tribes; Polans,

Silesians, Vistulans, Mazurians, Pomeranians and Mazovians.

In 966 the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I the Great affirmed the ducal title held by the Polanes leader

Mieszko I. Once Mieszko was converted to Christianinty, he then believed he was given the right to go out and conquer land of all his neighbors in the name of his new faith.

During the massive expansion attempts of the Polans into the neighbouring territories, they pushed away the other groups.

Mieszko also allied with the Czechs to try to keep the German land conquered or received as lien for themselves.

The lands of present day Poland were populated by many different Slavic tribes; Polans,

Silesians, Vistulans, Mazurians, Pomeranians and Mazovians.

In 966 the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I the Great affirmed the ducal title held by the Polanes leader

Mieszko I. Once Mieszko was converted to Christianinty, he then believed he was given the right to go out and conquer land of all his neighbors in the name of his new faith.

During the massive expansion attempts of the Polans into the neighbouring territories, they pushed away the other groups.

Mieszko also allied with the Czechs to try to keep the German land conquered or received as lien for themselves.

In 972 the Germans under Margrave Hodo invaded Poland. Germans had mostly heavy cavalry forces.

The Polish cavalry lead the charging German forces into a trap near Cedynia. The German column

was then attacked from all sides and forced to retreat in the only direction

they could - right into a swamp. Here they were cornered and cut to pieces.

German losses were significant. Thietmar claims that most of the best knights were killed, apart from Hodo and Sigfried.

In 972 the Germans under Margrave Hodo invaded Poland. Germans had mostly heavy cavalry forces.

The Polish cavalry lead the charging German forces into a trap near Cedynia. The German column

was then attacked from all sides and forced to retreat in the only direction

they could - right into a swamp. Here they were cornered and cut to pieces.

German losses were significant. Thietmar claims that most of the best knights were killed, apart from Hodo and Sigfried.

The Mongols decimated many countries to the east. Nearly all Russia became tributary to the

Mongols. The scouts of Khan Ougedei reached Germany and France !

In 1241 a combined force of Poles and Germans sent by the Pope, attempted to halt the Mongols.

In the battle of Leignitz (Legnica) the best Polish knights, Teutonic Knights, Templars and

the flower of German knights perished.

The Mongols decimated many countries to the east. Nearly all Russia became tributary to the

Mongols. The scouts of Khan Ougedei reached Germany and France !

In 1241 a combined force of Poles and Germans sent by the Pope, attempted to halt the Mongols.

In the battle of Leignitz (Legnica) the best Polish knights, Teutonic Knights, Templars and

the flower of German knights perished.

The loss of Poland's access to the Baltic Sea resulted in a 150-year long period of wars

between Poland and the Teutonic Order.

In 1337 Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV allegedly granted the Order the imperial privilege

to conquer all Lithuania and Russia. During the reign of Grand Master von Kniprode,

the Order reached the peak of its international prestige and hosted numerous foreign crusaders and nobility.

The loss of Poland's access to the Baltic Sea resulted in a 150-year long period of wars

between Poland and the Teutonic Order.

In 1337 Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV allegedly granted the Order the imperial privilege

to conquer all Lithuania and Russia. During the reign of Grand Master von Kniprode,

the Order reached the peak of its international prestige and hosted numerous foreign crusaders and nobility.

"The only higher officials to escape from the battle were Grand Hospital Master and Komtur

of Elbing. Such a slaughter of noble knights and personalities was quite unusual in Medićval Europe.

This was possible mostly due to the participation of the peasantry who joined latter stages

of the battle, and took part in destruction of the surrounded

Teutonic troops. Unlike the noblemen, the peasants did not receive any ransom for taking

captives; they thus had less of an incentive to keep them alive." ( wikipedia.org 2007)

"The only higher officials to escape from the battle were Grand Hospital Master and Komtur

of Elbing. Such a slaughter of noble knights and personalities was quite unusual in Medićval Europe.

This was possible mostly due to the participation of the peasantry who joined latter stages

of the battle, and took part in destruction of the surrounded

Teutonic troops. Unlike the noblemen, the peasants did not receive any ransom for taking

captives; they thus had less of an incentive to keep them alive." ( wikipedia.org 2007)

Meanwhile the Ottoman Empire invaded Europe, and the Emperor,

Charles V, demanded that the Teutonic Knights and Poles stop their hostilities and aid the defense

of Europe against the infidels.

During the truce, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albert, was advised by Martin Luther to abandon the rules of his Order,

and to convert Prussia into a hereditary duchy for himself. Albert agreed, converted to Lutheranism, and resigned from the

Hochmeister office to assume the Prussian Homage from his uncle Sigismund I the Old, King of Poland,

the hereditary rights to the now-secularized Duchy of Prussia as a vassal of the Polish Crown.

Meanwhile the Ottoman Empire invaded Europe, and the Emperor,

Charles V, demanded that the Teutonic Knights and Poles stop their hostilities and aid the defense

of Europe against the infidels.

During the truce, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albert, was advised by Martin Luther to abandon the rules of his Order,

and to convert Prussia into a hereditary duchy for himself. Albert agreed, converted to Lutheranism, and resigned from the

Hochmeister office to assume the Prussian Homage from his uncle Sigismund I the Old, King of Poland,

the hereditary rights to the now-secularized Duchy of Prussia as a vassal of the Polish Crown.

The military and political victories, and the development of economy and culture,

strengthened Poland and the dynasty of the Jagiellons. In the latter part of the 15th century the Jagiellons

were gaining the upper hand in the competition against the Luxemburgers and the Habsburgs.

The military and political victories, and the development of economy and culture,

strengthened Poland and the dynasty of the Jagiellons. In the latter part of the 15th century the Jagiellons

were gaining the upper hand in the competition against the Luxemburgers and the Habsburgs.

The Polish army was never large but it was of excellent quality.

The infantry and artillery were fine, while the cavalry was arguably the best in Europe.

During the Golden Age the Polish troops enjoyed several spectacular victories.

Majority of them were due to the husaria or

"winged knights", as they are called in English-speaking world, or "Flügelhusaren" in German.

The Polish army was never large but it was of excellent quality.

The infantry and artillery were fine, while the cavalry was arguably the best in Europe.

During the Golden Age the Polish troops enjoyed several spectacular victories.

Majority of them were due to the husaria or

"winged knights", as they are called in English-speaking world, or "Flügelhusaren" in German.

The winged knights were the terror of infantry and cavalry,

Swedes, Russians, Turks, and the French and British mercenaries

and anyone who met them in battle. They were the tanks of XVI-XVII Century.

It was said that if the sky fell the Winged Knights' lances would support it,

while Maurice de Saxe, the French marshal and military writer proposed

the creation of a French cavalry modelled on these knights.

The winged knights were the terror of infantry and cavalry,

Swedes, Russians, Turks, and the French and British mercenaries

and anyone who met them in battle. They were the tanks of XVI-XVII Century.

It was said that if the sky fell the Winged Knights' lances would support it,

while Maurice de Saxe, the French marshal and military writer proposed

the creation of a French cavalry modelled on these knights.

There are numerous articles and books in Poland about the winged knights.

The film "With Fire and Sword" drew 7.5 million viewers in Poland in 7 months,

outdrawing the famous movie "Titanic."

This film portrays Renaissance Poland and the winged knights in several actions.

There are Winged Knights in the movie "Potop" (Deluge) filmed in 1974-5.

This film had an academy award nomination but did not win.

There are numerous articles and books in Poland about the winged knights.

The film "With Fire and Sword" drew 7.5 million viewers in Poland in 7 months,

outdrawing the famous movie "Titanic."

This film portrays Renaissance Poland and the winged knights in several actions.

There are Winged Knights in the movie "Potop" (Deluge) filmed in 1974-5.

This film had an academy award nomination but did not win.

The victors took many prisoners incl. Russian commander Ivan Cheladnin,

and all 300 guns.

Due to the spectacular proportions of the defeat, information about

the Battle of Orsha was suppressed in Muscovite chronicles. Even reputable historians of

the Russian Empire such as Sergei Soloviov rely on non-Russian sources.

The victors took many prisoners incl. Russian commander Ivan Cheladnin,

and all 300 guns.

Due to the spectacular proportions of the defeat, information about

the Battle of Orsha was suppressed in Muscovite chronicles. Even reputable historians of

the Russian Empire such as Sergei Soloviov rely on non-Russian sources.

At Kluszyn (not far from

At Kluszyn (not far from  In 1605 at Kircholm 4,000 Poles (incl.

2.000 winged - knights) with 5 guns under Chodkiewicz defeated 12,000 Swedes

with 11 guns deployed in an advantageous position.

The Poles used a feint to force the enemy off their high position.

The Swedes were routed on both wings and the infantry in the centre was

attacked from three sides simultaneously. The Swedish army collapsed in flight.

The battle was decided in 20 minutes by the devastating charge of winged knights.

In 1605 at Kircholm 4,000 Poles (incl.

2.000 winged - knights) with 5 guns under Chodkiewicz defeated 12,000 Swedes

with 11 guns deployed in an advantageous position.

The Poles used a feint to force the enemy off their high position.

The Swedes were routed on both wings and the infantry in the centre was

attacked from three sides simultaneously. The Swedish army collapsed in flight.

The battle was decided in 20 minutes by the devastating charge of winged knights.

The Turkish army at Chocim (Khotyn) consisted of 35.000 men (incl. elite cavalry)

and 50-120 guns. The Turks held the Chocim castle and well entrenched camp.

The Polish forces comprised of 30.000 men and 65 guns and were led by Jan Sobieski.

"The east of the camp was defended by the Dniestr, from the North and from the south deep the ravines about steep,

bold braes. The western side was most exposed, so they had raised and strengthened the walls with palings, and