|

.

Suvorov was one of the greatest military commanders who ever lived.

He was easily in the same league as Alexander the Great,

George Patton, and Hannibal.

|

The commander, his tactics and strategy.

"Act solely on the offensive.

Speedy marches, impetus in the attack, cold steel.

... Never split your forces to guard a variety of points."

- Suvorov to de Lumian, 1798

When Suvorov finally rose to command in the 1760s and 1770s, he burst into this well-ordered world as an innovator, a field commander whose tactical and operational conceptions were often at variance with European military convention.

On his arrival in Italy he laid down that the correspondence among generals must be brief and to the point (and devoided of honorifics) Officers and generals who failed it were called "know-nothings" by Suvorov. He expected the reports to be exact and specific, without the "casualties being considerable" or "large force of enemy."

When Suvorov finally rose to command in the 1760s and 1770s, he burst into this well-ordered world as an innovator, a field commander whose tactical and operational conceptions were often at variance with European military convention.

On his arrival in Italy he laid down that the correspondence among generals must be brief and to the point (and devoided of honorifics) Officers and generals who failed it were called "know-nothings" by Suvorov. He expected the reports to be exact and specific, without the "casualties being considerable" or "large force of enemy."

In contrast with the languid methods and tactics of his day, Sovorov marched rapidly, struck unexpectedly, attacked seemingly helter-skelter from a variety of formations, and pursued relentlessly. ... Whether in combat against Polish rebels, Tatar tribesmen, Turkish janissaries, French revolutionaries, or Prussian grenadiers, Suvorov’s stress on thorough preparation and speedy execution was sufficient to produce threescore major and minor victories, often in the face of hopeless odds. (- Bruce Menning)

Even the best commanders had weaknessesses and made mistakes.

Suvorov was not perfect general, his weaknesses were:

- despite putting great emphasis on the rapidity of movements,

officers with reports were frequently forced to wait half a day

(Suvorov was drank and asleep !)

- absence of interest in logistics and staff work.

For this reason the services of Austrian staff officers

were priceless to Suvorov.

Suvorov's Strategy.

"Speedy marches ... [and] ... Never split your forces

to guard a variety of points." - Suvorov

In strategy the speed was probably the most important thing for Suvorov.

When the Austrian generals complained to Suvorov on the rapidity of the marches and the suffering of the infantry as they marched through the rain-filled terrain, the fieldmarshal replied: "It comes to my attention that certain people complain that the infantry have got their feet wet. That is what happens in wet weather ... Only women, dandies, and slugabeds want to keep their feet dry. In future any loudmouth who complains against the imperial service will be dismissed from his command as a big-head. ..." Stragglers who complained were beaten with ramrods, while the Cossacks who policed the rear and the flanks were delighted to torment the suffering Austrians. Suvorov's troops (with artillery) were able to cover 60 km in 24 hours.

It tells volumes about Suvorov's ability to drive his troops.

In the war against France Suvorov recommended to send 100,000 Austrians and 100,000 Russians across the middle Rhine River, directly on Paris. Tzar Paul ignored it, for he preferred to engage the armies on several fronts.

When the French put their trust in dispersal and static obstacles (ridges, rivers etc.)

Suvorov staked everything on concentration and speed.

When the French put their trust in dispersal and static obstacles (ridges, rivers etc.)

Suvorov staked everything on concentration and speed.

In Italy he explained his intentions to the Austrian generals in a few rushed phrases, and launched an offensive which swept along the northern edge of the plains under the Alps.

The troops were forced to march in Suvorovian style, and Bagration took the lead with the Russian advance guard. Suvorov had effected a decisive concentration of troops on the upper Adda River and then crushed the enemy. The victory on the Adda River broke the French army in northern Italy and opened the way to the liberation of Piedmont. Suvorov was successful everywhere.

Unfortunately instead of invading France, the monarchs and politicians sent Suvorov to

Switzerland to replace the Austrian element of an Austro-Russian army.

Meanwhile French General Massena defeated the 20,000-man Russian army of Rimsky-Korsakov at Zürich. That left Suvorov's 18,000 men, exhausted and short of provisions, to face Masséna's 80,000 troops.

Unfortunately instead of invading France, the monarchs and politicians sent Suvorov to

Switzerland to replace the Austrian element of an Austro-Russian army.

Meanwhile French General Massena defeated the 20,000-man Russian army of Rimsky-Korsakov at Zürich. That left Suvorov's 18,000 men, exhausted and short of provisions, to face Masséna's 80,000 troops.

The only alternative to annihilation was to undertake a historically unparalleled withdrawal over the Alps. The French reached Glarus first, but Suvorov evaded the trap by redirecting his troops through the village of Elm.

On October 6 Suvorov commenced a trek through the deep snows of Panixer Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland.

The 70-years old fieldmarshal led his troops over three alpine passes in 10 days. Many Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, but Suvorov, never admitting that he was retreating, eventually escaped encirclement and reached the Rhine River with the bulk of his army intact.

On October 6 Suvorov commenced a trek through the deep snows of Panixer Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland.

The 70-years old fieldmarshal led his troops over three alpine passes in 10 days. Many Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, but Suvorov, never admitting that he was retreating, eventually escaped encirclement and reached the Rhine River with the bulk of his army intact.

Suvorov's Alpine feat gained the grudging admiration of the astonished French and earned him the nickname of the Russian Hannibal, but it did nothing to improve his standing with the Russian monarch, who, disgusted with Austrian policy and conduct, withdrew from the coalition.

( Source: www.avantart.com)

The New York Times writes: "Suvorov, considered the most brilliant of all Czarist generals, carried out one of the most extraordinary feats in either the Alps or the history of warfare - a sort of late 18th-century Dunkirk achieved without rescuers." (Article "Where Cossacks Crossed the Alps" by Marcia Lieberman, March 6, 2007)

American writer, J. T. Headley wrote that Hannibal's exploits (ext.link) were "mere child's play beside it."

Suvorov's Tactics.

As for the battle formations, the line was to be used against

European troops [French,Poles,Prussians] and squares against the Turks.

Columns were for movement.

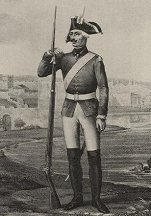

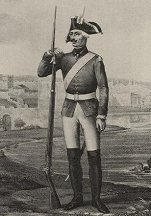

Pictures: Russian musketier 1763-1786 (left),

Pictures: Russian musketier 1763-1786 (left),

and grenadier of musketier regiment 1786-1796 (right).

Pictures by Viskovatov, Russia,

Suvorov's tactics were based on columnar formation for the approach, and deployment into line for combat. His infantry often took cover, for example at Novi entire jagers regiments were hidden in the wheat and barley field. His line infantry were often placed behind a ridge or houses.

Suvorov's cavalry was expected to attack in two lines in chequer formation, leaving intervals between the squadrons so that the second line can break through the gaps in case the attack of the first line was thrown back. The order 'Halt !' was forbidden during action - it was only for the parade ground. The cavalry and Cossacks pursued the enemy.

Suvorov put his exceptionally successful tactics into few words.

"An attack against the enemy centre was inadvisable. An attack against the rear was the most advantegous of all, through it was practicable only for smaller bodies.

As for the battle formations, the line was to be used against western European troops, and squares against the Turks. There were three fundamental military principles:

- coup d'oeil an eye for situation and ground

- speed

- impetus

(Duffy - "Eagles over the Alps" pp 16-17)

Suvorov versus French generals.

British historian Christopher Duffy declared that

"Suvorov would have beaten Bonaparte in 1800,

and can only regret that he never had the opportunity."

Seven future French marshals campaigned against the 70-years old Suvorov in 1799, and only St.Cyr escaped the unhappy experience which overtook Grouchy, Macdonald, Mortier, Perignon, Serurier and Victor.

For his victory over Joubert, Suvorov was named "the first commander in Europe."

For his victory over Joubert, Suvorov was named "the first commander in Europe."

General Berthelemy Joubert (1769-1799) had been marked out as a future great captain by Napoleon himself. After the battle, his remains were brought to France and buried in Fort La Malgue, and the Directory paid tribute to his memory by a ceremony of public mourning.

He "was a pure product of the Revolution, and ... won golden opinions from Bonaparte in Italy in 1796. Bonaparte now prized Joubert as a reliable man to leave in the European theatre, when the best of the French troops were campaigning in the Orient; the Directory valued him as a soldier who would bolster its military credit while being innocent of political designs."

(Duffy - "Eagles over the Alps" p 130)

When Joubert took command over the army facing Suvorov, four future marshals held important posts or commands: Grouchy as a divisional commander, Suchet as chief of staff, Perignon as lef wing commander, and St.Cyr as right wing commander.

Generals Scherer and Moreau were defeated in the opening stages of the Italian campaign, and a third of that rank, Serurier, was taken prisoner. Jean Serurier was an able and trustworthy soldier who had a lengthy military career.

The campaign and battle of Trebbia produced a further crop of trophies: General Macdonald had been sabered outside Modena and was now wounded in the same culminating battle which left General Victor wounded, and the acting divisional commanders Olivier and Rusca not only bleeding but captured.

The campaign and battle of Trebbia produced a further crop of trophies: General Macdonald had been sabered outside Modena and was now wounded in the same culminating battle which left General Victor wounded, and the acting divisional commanders Olivier and Rusca not only bleeding but captured.

Victor earned his marshal's baton at Friedland in 1807.

Sent to Spain, Victor had some successes - defeating Spanish troops at Espinosa and Medillin - but lost several battales to the British.

In 1815, after Waterloo Marshal Victor voted for Marshal Ney's death.

After three days' fighting at Trebbia, Macdonald retired to Genoa. In 1800 Etienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre MacDonald received the command of the French troops in Switzerland which was to maintain the communications between the armies of Germany and of Italy. He carried out his orders to the letter. In Wagram in 1809 he commanded the famous column of attack. After the Battle of Leipzig, he was ordered with Prince Poniatowski to cover the evacuation of Leipzig; after the blowing up of the bridge, he managed to swim the Elster, while Poniatowski was drowned. During the campaign of 1814 in France, Macdonald distinguished himself.

After three days' fighting at Trebbia, Macdonald retired to Genoa. In 1800 Etienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre MacDonald received the command of the French troops in Switzerland which was to maintain the communications between the armies of Germany and of Italy. He carried out his orders to the letter. In Wagram in 1809 he commanded the famous column of attack. After the Battle of Leipzig, he was ordered with Prince Poniatowski to cover the evacuation of Leipzig; after the blowing up of the bridge, he managed to swim the Elster, while Poniatowski was drowned. During the campaign of 1814 in France, Macdonald distinguished himself.

At Novi the French commander Joubert was killed outright, which cut short a career of exceptional promise, while Generals Grouchy and Perignon followed fashion being disabled by wounds and falling in the hands of the Allies. Grouchy received 14 wounds !

At Novi the French commander Joubert was killed outright, which cut short a career of exceptional promise, while Generals Grouchy and Perignon followed fashion being disabled by wounds and falling in the hands of the Allies. Grouchy received 14 wounds !

The names by themselves indicate that Suvorov was by no means dealing with the second line of French commanders in 1799.

In 1799 Emmanuel de Grouchy distinguished himself greatly as a divisional commander in the campaign against the Austrians and Russians.

He served in Austria in 1805, in Prussia in 1806, Poland in 1807, where he distinguished himself at Eylau and Friedland, Russia in 1812, Germany in 1813, France in 1814, and Belgium in 1815. After the battle of Ligny he was appointed to command the right wing to pursue the Prussians.

"The question is sometimes put as to who would have won, if Suvorov had remained in the southern theatre of war, stay in good health, and encountered Bonaparte in 1800.

... The two mens' opinions of one another now become of some interest.

"The question is sometimes put as to who would have won, if Suvorov had remained in the southern theatre of war, stay in good health, and encountered Bonaparte in 1800.

... The two mens' opinions of one another now become of some interest.

Much later the considered judgement of Bonaparte, or rather Napoleon, was that Suvorov had 'the soul of a great commander, but not the brains. He was extremely strong willed, he was amazingly active and utterly fearless - but he was as devoid of genius as he was ignorant of the art of war."

Suvorov followed Bonaparte's career with the closest interest, and he once exclaimed to Roverea: "That man had stolen my secret, the speed of my marches !"

Suvorov had written in 1796: "The young Bonaparte, how he moves ! He is a hero, a giant, a magician. He overcomes nature and he overcomes men. He turned the Alps as if they did not exist ... My conclusion is this. That as long as General Bonaparte keeps his wits about him he will be victorious; he possesses the higher elements of the military art in a happy balance. But if, unfortunately for him, he throws himself into the whirlpool of politics, he will lose the coherence of his thoughts and he will be lost." (- Christopher Duffy)

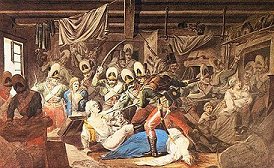

Battle of Novi, August 1799.

"... two great armies were engaged for more than 12 hours

... it was one of the most remarkable combats of infantry

which have taken place since the invention of firearms."

- Anon., "The History of the Campaign of 1799, in Italy"

On August 15 1799 at Novi Suvorov defeated French army under General Joubert.

Suvorov had Austrian corps under Kray (Bellegarde's and Ott's troops), and Russian corps under Derfelden (Bagration, Miloradovich, Derfelden). Joubert's right wing was under St.Cyr, the center under Moreau, and the left wing was under Perignon (Grouchy, Lemoine, and cavalry)

Griffith and Phipps gave 40,000 French and 50,000 Allies, Ross gave 60,000 French and 68,000 Allies. The Allies were slightly stronger but the French occupied the ridge near Novi, and their both flanks were strongly defended. The Novi town was protected by a medieval wall. The only weakness was that in case of a retreat it was a death-trap due to deep-cut valleys and steep banks in the rear.

The first shots were exchanged in very early morning (3:20 AM). Lemoine's and Grouchy's divisions and cavalry of the left wing were pushed back by the Austrians. The Austrians however had to negotiate the difficult terrain and the vineyards giving the enemy time to regain his composure. Bellegarde's and Ott's infantry were counterattacked and thrown back.

After 9 AM the whitecoats came in larger numbers and again resolutely marched up the slopes.

They were however thrown back by musket volleys and canister fire. One French brigade pursued the enemy down the slope but in the plain was charged by the Austrian cavalry. While General Partouneaux was taken prisoner his infantrymen were chased back to the ridge.

Kray deployed 40 Austrian guns and pounded the French on the ridge.

Before 10 AM Derfelden attacked Novi with Bagration's infantry.

They took the suburb but were halted by the city wall. The French counterattacked and with the aid of Watrin's division threw the Russians back. Miloradovich's infantry arrived and stabilized the front. Derfelden arrived with 6,100 troops and together with Bagration drove back Watrin's division. The Russian advance was halted by French skirmishers and artillery.

Before 3 PM the Russian grenadiers moved up the slope attempting a bayonet attack. The French on the ridge however delivered a deadly volley and the grenadiers fell back. The grenadiers then were chased by the French skirmishers towards Pozzolo.

Meanwhile Suvorov ordered Melas' Austrian corps (8,600 men) to join him. The bulk of Melas' corps was made of 9 grenadier battalions. Two grenadier battalions stormed the hill defended by Watrin's infantry and captured it without firing a single shot. The grenadiers however were unable to dislodge the French from houses and vineyards. What persuaded the French to abandon their positions was the arrival of 7 grenadier battalions and their advance (to sounding music) against the the French rear.

Meanwhile Suvorov ordered Melas' Austrian corps (8,600 men) to join him. The bulk of Melas' corps was made of 9 grenadier battalions. Two grenadier battalions stormed the hill defended by Watrin's infantry and captured it without firing a single shot. The grenadiers however were unable to dislodge the French from houses and vineyards. What persuaded the French to abandon their positions was the arrival of 7 grenadier battalions and their advance (to sounding music) against the the French rear.

Between 3 and 4 PM Kray's Austrian corps renewed his attack.

Novi was attacked frontally by the Russians and from the flank by Austrian grenadiers.

Gardanne's infantrymen kept firing from the walls and windows until the enemy penetrated the town. The French then fought their way out. Before 6 PM the French army fell back along the entire line. There was no contact between the two French wings. While Moreau managed to rally the right wing, the left wing was around Pasturana. Grouchy was unhorsed and taken prisoner, Perignon received a spectacular saber cut across his forehead and also captured.

Colli and his 2,000 infantrymen were taken prisoner. The French lost 16,000 killed, wounded and prisoners, and 36 guns, while the Austro-Russian army suffered only 8,000 casualties. In the night the noon shone brightly, though the powdersmoke was hanging in the air.

It was a disaster for the French.

|

Suvorov was born in 1729 to a middle-ranking family of Swedish origin (a Swede named Suvor who emigrated to Russia in 1622). His father was the author of the first Russian translation of the works of the famous French general Vauban. Suvorov was only 5 feet tall, but had heavy shoulders and arms.

Suvorov was born in 1729 to a middle-ranking family of Swedish origin (a Swede named Suvor who emigrated to Russia in 1622). His father was the author of the first Russian translation of the works of the famous French general Vauban. Suvorov was only 5 feet tall, but had heavy shoulders and arms.

Suvorov was the product of example, firmness of will, great gift of communication, and a brutality which was tempered with empathy with the soldiers under his command.

He entered military service as a private in the

Suvorov was the product of example, firmness of will, great gift of communication, and a brutality which was tempered with empathy with the soldiers under his command.

He entered military service as a private in the  Suvorov's name is linked with two of the crueliest episodes of that times.

The first is the massacre of 26,000 Turkish soldiers and civilians of Izmail in the Danube delta. Suvorov's troops suffered almost 33 % casualties in storming of Izmail and the survivors revenged themselves in a horrible way.

Suvorov's name is linked with two of the crueliest episodes of that times.

The first is the massacre of 26,000 Turkish soldiers and civilians of Izmail in the Danube delta. Suvorov's troops suffered almost 33 % casualties in storming of Izmail and the survivors revenged themselves in a horrible way.

Bruce Menning writes: "... Suvorov would refine more than four decades of experience into a simple set of guidelines to govern the training and indoctrination of soldiers in the fundamentals of the military art. His prescriptions, known as The Art of Victory, were initially circulated in manuscript form, temporarily forgotten after his death, then published and reprinted eight times between 1806 and 1811. ... Although 'The Art of Victory' dates to 1795, evidence shows that Suvorov first professed systematic views on training during the 1760s, when he returned from the Prussian campaigns to assume successive command of the Astrakhan and Suzdal infantry regiments.

Bruce Menning writes: "... Suvorov would refine more than four decades of experience into a simple set of guidelines to govern the training and indoctrination of soldiers in the fundamentals of the military art. His prescriptions, known as The Art of Victory, were initially circulated in manuscript form, temporarily forgotten after his death, then published and reprinted eight times between 1806 and 1811. ... Although 'The Art of Victory' dates to 1795, evidence shows that Suvorov first professed systematic views on training during the 1760s, when he returned from the Prussian campaigns to assume successive command of the Astrakhan and Suzdal infantry regiments.

In 1796 and 1798 were issued so-called The Infantry Codes.

Suvorov dismissed them as a "rat-chewed package found in a castle" and made no attempt to enforce them among his troops. Suvorov wrote: "Russians have always beaten Prussians, so what would we want to borrow from them?" When Suvorov received wooden rulers to measure soldiers' queues and side curls, he said, "Hair powder is not gunpowder, curls are not cannons, a queue is not a sword, and I am not a German..."

In 1796 and 1798 were issued so-called The Infantry Codes.

Suvorov dismissed them as a "rat-chewed package found in a castle" and made no attempt to enforce them among his troops. Suvorov wrote: "Russians have always beaten Prussians, so what would we want to borrow from them?" When Suvorov received wooden rulers to measure soldiers' queues and side curls, he said, "Hair powder is not gunpowder, curls are not cannons, a queue is not a sword, and I am not a German..."  When Suvorov finally rose to command in the 1760s and 1770s, he burst into this well-ordered world as an innovator, a field commander whose tactical and operational conceptions were often at variance with European military convention.

On his arrival in Italy he laid down that the correspondence among generals must be brief and to the point (and devoided of honorifics) Officers and generals who failed it were called "know-nothings" by Suvorov. He expected the reports to be exact and specific, without the "casualties being considerable" or "large force of enemy."

When Suvorov finally rose to command in the 1760s and 1770s, he burst into this well-ordered world as an innovator, a field commander whose tactical and operational conceptions were often at variance with European military convention.

On his arrival in Italy he laid down that the correspondence among generals must be brief and to the point (and devoided of honorifics) Officers and generals who failed it were called "know-nothings" by Suvorov. He expected the reports to be exact and specific, without the "casualties being considerable" or "large force of enemy."

When the French put their trust in dispersal and static obstacles (ridges, rivers etc.)

Suvorov staked everything on concentration and speed.

When the French put their trust in dispersal and static obstacles (ridges, rivers etc.)

Suvorov staked everything on concentration and speed.

Unfortunately instead of invading France, the monarchs and politicians sent Suvorov to

Switzerland to replace the Austrian element of an Austro-Russian army.

Meanwhile French General Massena defeated the 20,000-man Russian army of Rimsky-Korsakov at Zürich. That left Suvorov's 18,000 men, exhausted and short of provisions, to face Masséna's 80,000 troops.

Unfortunately instead of invading France, the monarchs and politicians sent Suvorov to

Switzerland to replace the Austrian element of an Austro-Russian army.

Meanwhile French General Massena defeated the 20,000-man Russian army of Rimsky-Korsakov at Zürich. That left Suvorov's 18,000 men, exhausted and short of provisions, to face Masséna's 80,000 troops.

On October 6 Suvorov commenced a trek through the deep snows of Panixer Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland.

The 70-years old fieldmarshal led his troops over three alpine passes in 10 days. Many Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, but Suvorov, never admitting that he was retreating, eventually escaped encirclement and reached the Rhine River with the bulk of his army intact.

On October 6 Suvorov commenced a trek through the deep snows of Panixer Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland.

The 70-years old fieldmarshal led his troops over three alpine passes in 10 days. Many Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, but Suvorov, never admitting that he was retreating, eventually escaped encirclement and reached the Rhine River with the bulk of his army intact.

Pictures: Russian musketier 1763-1786 (left),

Pictures: Russian musketier 1763-1786 (left),  For his victory over Joubert, Suvorov was named "the first commander in Europe."

For his victory over Joubert, Suvorov was named "the first commander in Europe." The campaign and battle of Trebbia produced a further crop of trophies: General Macdonald had been sabered outside Modena and was now wounded in the same culminating battle which left General Victor wounded, and the acting divisional commanders Olivier and Rusca not only bleeding but captured.

The campaign and battle of Trebbia produced a further crop of trophies: General Macdonald had been sabered outside Modena and was now wounded in the same culminating battle which left General Victor wounded, and the acting divisional commanders Olivier and Rusca not only bleeding but captured.

After three days' fighting at Trebbia, Macdonald retired to Genoa. In 1800 Etienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre MacDonald received the command of the French troops in Switzerland which was to maintain the communications between the armies of Germany and of Italy. He carried out his orders to the letter. In

After three days' fighting at Trebbia, Macdonald retired to Genoa. In 1800 Etienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre MacDonald received the command of the French troops in Switzerland which was to maintain the communications between the armies of Germany and of Italy. He carried out his orders to the letter. In  At Novi the French commander Joubert was killed outright, which cut short a career of exceptional promise, while Generals Grouchy and Perignon followed fashion being disabled by wounds and falling in the hands of the Allies. Grouchy received 14 wounds !

At Novi the French commander Joubert was killed outright, which cut short a career of exceptional promise, while Generals Grouchy and Perignon followed fashion being disabled by wounds and falling in the hands of the Allies. Grouchy received 14 wounds !

"The question is sometimes put as to who would have won, if Suvorov had remained in the southern theatre of war, stay in good health, and encountered Bonaparte in 1800.

... The two mens' opinions of one another now become of some interest.

"The question is sometimes put as to who would have won, if Suvorov had remained in the southern theatre of war, stay in good health, and encountered Bonaparte in 1800.

... The two mens' opinions of one another now become of some interest.

Meanwhile Suvorov ordered Melas' Austrian corps (8,600 men) to join him. The bulk of Melas' corps was made of 9 grenadier battalions. Two grenadier battalions stormed the hill defended by Watrin's infantry and captured it without firing a single shot. The grenadiers however were unable to dislodge the French from houses and vineyards. What persuaded the French to abandon their positions was the arrival of 7 grenadier battalions and their advance (to sounding music) against the the French rear.

Meanwhile Suvorov ordered Melas' Austrian corps (8,600 men) to join him. The bulk of Melas' corps was made of 9 grenadier battalions. Two grenadier battalions stormed the hill defended by Watrin's infantry and captured it without firing a single shot. The grenadiers however were unable to dislodge the French from houses and vineyards. What persuaded the French to abandon their positions was the arrival of 7 grenadier battalions and their advance (to sounding music) against the the French rear.

"The bullet's an idiot, the bayonet's a fine chap."

"The bullet's an idiot, the bayonet's a fine chap."