Infantry Tactics and Combat

during the Napoleonic Wars.

~ Part 2 ~

"If you had seen one day of war, you would pray to God

that you would never see another." - Napoleon

1. Introduction.

2. Lines.

2. Lines.

Depth of Line >

The Thin Red Line >

The French and Two Ranks >

3. Columns.

Advantages of Columns >

Disadvantages of Columns >

Multi-battalion Columns >

4. Ordre-Mixte.

5. Squares Against Cavalry.

Solid Squares >

Egyptian Squares >

Multi-battalion Squares >

Squares in Combat 1 >

Squares in Combat 2 >

Squares in Combat 3 >

Cavalry Break Into Square >

Artillery vs Square >

Line and Column vs Cavalry >

The Rare Thing >

Miscallenous >.

6. Skirmishers, skirmishing.

French Skirmishers >

Russian Skirmishers >

British Skirmishers >

Prussian and Austrian Skirmishers >

Rifles >

|

Introduction.

Any officer and general had to master the tactical maneuvers and formations.

They had to have a grasp of the terrain and be able to quickly estimate distance in order

to execute a given formation. Constant and repetitive practice was essential.

The infantrymen were either formed at open or closed files:

Several companies formed battalion.

The battalion could be formed in:

French infantry - 0.325 m Russian infantry - 0.35 m British infantry - 0.63 m Prussian infantry - 0.66 m Austrian infantry - 1.25 m

The intervals between first and second line of battalions were between 100 and 400 paces.

Theoretically if any of the battalions of first line was broken the battalions

from the second line would counterattack the enemy from the flanks.

Quite often however the broken battalion of first line run toward the second line and disordered it.

Also the sight of own troops fleeing in panic was enough for the nerves of troops in the

second line.

|

|

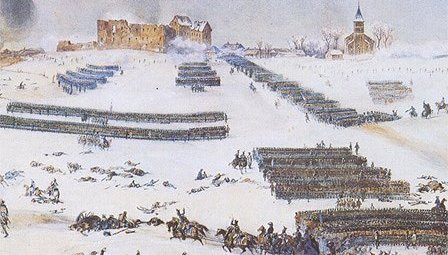

Lines. The line had been standard during the XVIII Century but lost popularity after the French triumphs with columns during the Revolutionary Wars. The difficulty with advancing lines was their sensitivity to terrain and order. The irregularities of the terrain caused the ranks to become ragged, the battalion bowed in the middle and sometimes broke completely in half. A line of two battalions on a battlefield would be halting to dress more frequently than one battalion. The long line made the troop more difficult to manoeuvre and to turn. For these reasons, commanders used lines only for short distances and over open terrain with no serious obstacles.

It was easier to attack with several battalion columns than with several battalion

lines. General Antoine Henri Jomini wrote: "I have also seen attempts made to march deployed

battalions in checkerwise order. They succeeded well; whilst marches of the same battalions

in continous lines did not. The French, particularly, have never been able to march steadily

in deployed lines... It maybe employed in the first stages of the movement forward, to make it more easy,

and the rear battalions would then come into line with the leading ones before reaching

the enemy ... for we must not forget that in the checkered order there are not two lines,

but a single one, which is broken, to avoid the wavering and disorder observed in the marches

of continous lines...

Fig. 1:

Fig. 2:

Fig. 3:

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

.

.

Fig. 19 . Long before Napoleonic wars the line of infantry was 4 and 5 ranks deep formation. Improving quality of firearms made possible to 'lighten' the line. In 1703 the British went from 4-rank deep lines to only 3-rank deep. The rest of Europe followed them. The Prussians were the next in 1740, the French in 1754 and the Austrians in 1757. By the end of XVIII century all armies formed their infantry on 3-ranks. In most European armies of the Napoleonic Wars, when casualties were heavy the men were drawn from the 3rd rank and placed into the 1st and 2nd rank to maintain the proper frontage of the company. Sometimes the 3rd rank would disappear completely. According the French Regulations of 1791, Ecole de Peloton p. 101, once company was reduced below 12 files it was to be formed on 2 ranks. The 2-rank system was first introduced by the Prussians during the Seven Years War. The intention was to bring more muskets to bear but soon was discovered that cavalry could easily rout such thin formation. Fortescue's summary of infantry tactics of the Seven Years War: "The number of ranks was left unfixed, being increased or reduced according to the frontage required, but probably seldom exceeded 3 and was occasionally reduced to two." In 1794 Austrian General Mack's Instructionspunkte recommended that the 3rd rank be used to extend the infantry line and was dictated by circumstances and terrain. During the Napoleonic Wars some German armies had their infantry formed on 2 ranks only. For example until 1809 the Wirtembergian light troops were formed on 2 ranks. In Prussia and Austria the 3rd rankers were extensivelly used as skirmishers and often were detached from their companies. Until 1807 in Russia all jager regiments were formed on 2 ranks.

Officially the British infantry was formed in 3 ranks. However during the Napoleonic Wars

they had their infantry formed on 2 ranks only. (At Waterloo most of their battalions

were formed on 4 ranks.)

The British tactics was much influenced by the American experience.

In that period there was a great deal of bickering about the makeup of the British infantry.

"The basic tactical requirement in North America was for a looser, more flexible system, based on small bodies of men

fighting in rough lines, often of one rank and never more than two; the 3rd rank had never been of great value as far as

fire power was concerned, and in thick country it became a positive menace." (Warminster - "The British Infantry

1660-1945" publ. in 1983)

The French and Two Ranks. The French infantry was formed on 3 ranks. They however experimented with the 2-ranks in 1775-1776 and again in 1788. Already from 1791 on peace footing they would frequently drill in 2 ranks. During campaign, when casualties were heavy, the men were drawn from the 3rd rank and placed into the 1st and 2nd rank to maintain the proper frontage of the company. According the French Regulations of 1791, Ecole de Peloton p. 101, once company was reduced below 12 files it was to be formed on 2 ranks. In October 1813, Napoleon wanted to increase the length of the battleline of his depleted infantry by 30 % and on October 13th 1813 was issued order: " ... Emperor orders the entire infantry of the army to form up in 2 ranks instead of 3, in that his Majesty regarded that the fire and the bayonet of the 3rd rank useless." Thus in the Battle of Leipzig the French infantry was formed on 2 ranks. But Ney's infantry was still formed on 3 ranks, he believed in deep formations. According to George Nafziger however this reoganization of infantry in the midst of a hard fought campaign "may or may not have occured." ( Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets" p 60) On secondary theaters of war, in Spain and Italy, the French kept their infantry formed on 3 ranks. Napoleon's orders needed time to arrive from Leipzig in Germany to the remote Spain and not every general was convinced to the new formation.

French Marshal Ney's "Military Studies - Instructions for the Troops composing the Left Corps" in

the section "Observations upon different modes of firing" on pages 99-101: "The firing of 2 ranks, or file firing, is, with the

exception of a very few movements, absolutely the only kind of firing which offers much greater advantages to infantry... Most infantry

officers must have remarked the almost insurmountable difficulty they find in stopping file-firing during battle, after it has once

begun, especially when the enemy is well within shot; and this firing, in spite of the command given by the field officers, resembles

general discharges.

Examples of napoleonic infantry being formed on 2 ranks in combat:

|

|

Columns.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

.

.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

.

.

Fig. 23

Fig. 17

Fig. 16 Napoleon's Decree of 1808 stated that when the grenadier and voltigeur companies were present, the battalion of 6 companies would act by divisions. If the flank companies (grenadiers and voltigeurs) were detached from their parent battalion, the battalion would act by platoons, with each company constituting a "platoon". Such column would have front on one company (instead of two) and be 12 ranks deep (instead of 9 ranks). The diagram below is for battalion of 6 companies. Columns were called by their frontage and depth. The frontage could be either division (here means just 2 companies) or platoon (means 1 company). The company was an administrative unit, the tactical unit was the platoon (peloton). The French company consisted of one platoon.

"The battalion column was a handy formation, capable of quick maneuver to its front, flanks, or rear; some officers described it as able to move like a single soldier. ... If the columns did come under enemy fire, it was best to have them in what the Reglament called a 'column of attack', which had twice as much distance between its divisions as the 'closed' column ... Once within striking distance, the column closed up, then went for the enemy line at the double with the bayonet ..." (- Colonel Elting)

In wargaming (ext.link) and popular literature the fight between two columns is a common thing.

The front ranks of columns fight each other, while the rear ranks pushed at each other almost

like rugby players. :-)

"The [British] artillery [at Coa] attached to the Reserve instantly opened fire upon it [French infantry columns] and such was the excellence of the practice, that the enemy's column, after a heavy loss, withdrew before it had been able to fire a musket." (Summerville - "March of Death" 129) If the column continue its advance, the stress or excitement can be such that they will start running. Breath of some men could run short already after 50-100 paces. Others were better runners. It created disorder and the column became a mob. Only few troops managed to keep their cool, and advance in orderly manner despite all odds. Most often the cannonbals passed over the columns. Most often the canister passed over the column or hit the ground before it. (In 1806 at Auerstadt the French 111th Line captured Prussian battery despite 6 volleys of canister.) Some of the shells' fuses were eiether cut too long or too short and the shells bursted prematurely. If the fuse was too long it was "snuffed out" by enemy's infantryman and the shell didn't explode. The shells if hurriedly produced proved unreliable. In 1813 at Lutzen approx. 1/3 of the French shells fired failed to explode. (Elting - "Swords Around a Throne" p 263)  Once the enemy began wavering, the NCOs of the battalion column would tight the ranks

up for the charge. The man wants company and in his hour of greatest danger his herd

instinct drives him toward his fellows. This is natural. The compact column made danger

more endurable. The moral impulse was stronger as one felt better supported from behind.

The strength of this column was in the threat of the bayonets and the shock power of the

compact formation. Every man close at hand was an aid in helping the individual soldier

choke down the fear which might otherwise have stopped him.

Once the enemy began wavering, the NCOs of the battalion column would tight the ranks

up for the charge. The man wants company and in his hour of greatest danger his herd

instinct drives him toward his fellows. This is natural. The compact column made danger

more endurable. The moral impulse was stronger as one felt better supported from behind.

The strength of this column was in the threat of the bayonets and the shock power of the

compact formation. Every man close at hand was an aid in helping the individual soldier

choke down the fear which might otherwise have stopped him.

The weakness of this type of column lied in the fact that officers had much less control over it. They were normally placed behind the companies, now there was no space for them and they took positions on the sides. It left the whole center of the column out of their control, turning it into mob and moving easily only forward, according to the impulses and threats.

British soldier Blakeney wrote after Albuera: "I saw their [French] officers endeavouring to deploy their columns, but all to no purpose. For as soon as the third of a company got out, they would immediately run back in order to be covered by the front of the column". The cowards took cover behind the brave creating gaps in the line. If the enemy noticed such behavior and attacked with bayonet, they would simply fall apart.

There were various scenarios of the infantry combat and sometimes cavalry or/and artillery

intervened. In 1813 at Dennewitz,

Marshal Ney attacked with infantry, artillery and cavalry.

In the head marched skirmishers, behind battalion columns of French and Italian

infantry drawn from Morand's and Fontanelli's divisions. These masses were supported by

cavalry and artillery. Ney advanced to within 80 paces of the lines of Prussian 4th

East Prussian Regiment and 5th Reserve Regiment. The 3rd East Prussian

Landwehr Reg. was in second line but soon joined the firefight.

Advantages of columns.

Disadvantages of columns.

- - - at Austerlitz some of the French columns were kept hidden behind a hill (Lannes') - - - at Friedland Ney's columns of French infantry stood in the wood - - - at Friedland upon arriving Victor's I Corps was placed in a fold of the terrain - - - at Ligny some French columns laid down in tall grass and corn-fields. - - - at Borodino, the Polish Vistula Legion were ordered to lay on the ground. Officers remained standing. - - - at Wagram, Austrian jäger battalion took cover in a drainage ditch. - - - at Wagram mass of 2.000 Austrian infantry was sheltered behind the earthen dike. - - - at Wagram the Austrian 47th Regiment laid down on the ground - - - at Wagram Austrian General Radetzky kept hundreds of infantrymen - - - in the safety of dry moat around the tower near Neusiedel. - - - at Katzbach, Prussian 7th Brigade (6,500 men) lay behind the heights Christianhohe, - - - at Ligny approx. 24-36 Prussian battalions were deployed in dead ground - - - in tall crops. Other battalions had been allowed to sit down (23rd Regiment.)

Multi-battalion columns. There were also multi-battalion columns. The size of column however was not as decisive as one may think. There were cases where smaller column defeated a larger column, small but brave troop routed big masses. Below are examples of multi-battalion 'columns' used during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1809 at Wagram, French Marshal Macdonald had formed his three infantry divisions (8,000 men in 23 battalions) in a huge 'column'. It was the largest column of the Napoleonic Wars. It can be however argued that it was in fact a large hollow rectangle or mixed-order formation, not the massive column so often described.

Macdonald later wrote that "I was far from thinking that this demonstration was to

be the main attack on the enemy's centre". This unusual formation was not adopted

because the infantrymen were inexperienced but because of the probability that it

would be attacked from three sides. Conspicious on his white charger,

Surprisingly only 1,500 - 3.000 reached the Austrian positions. Approx. 6.000-9.000 were wounded, killed, or lied on the ground as if they were hit. Once the danger passed they either joined their battalions or run to the rear. Such things took place virtually in every battle and in every army. (Even the iron-disciplined Prussian infantrymen of Frederick experienced it too. In 1757 at Prague, a Prussian officer was wounded and crawled away behind a hill where he was astounded to encounter a "great number of officers and NCOs. Some were wounded, but most were just looking for cover.")

The Russian cavalry charged and drove Ney's divisions back in disorder. It forced Bison's division (four regiments) to deploy and repulse the attackers. Marchand halted the flight of his troops and joined Bison's division. Under the cover of numerous skirmishers they formed their troops in mixed order (lines and columns). Russian lines and columns advanced against them and a huge fusillade began. Before it ended the Russian cavalry again charged and again Marchand's and Bision's regiments fled. Napoleon intervened with Dupont's infantry division and stabilized the situation. Dupont advanced rapidly from Posthenen, the French cavalry divisions drove back the Russian cavalry, and finally the artillery under Senarmont advanced a mass of guns to case-shot range. The Russian defence collapsed in a few minutes. Ney's exhausted infantry were able to pursue the broken Russian regiments into the streets of Friedland. Dupont distinguished himself for the second time by fording the mill-stream and assailing the left flank of the Russian centre. This offered very stubborn resistance, but the French forced the line backwards, and the battle was over.

The heavy infantry columns were also used at Waterloo.

Dozelot’s division almost reached the hedge, while Marcgnet’ division was within 50 m of the crest. One brigade of Durutte’s division was far behind and climbing the slope while the other marched towards Papelotte.

|

|

Ordre mixte Frenchman Guibert developed the mixed order (ordre mixte). He advocated the use of both lines and columns in the attack by acting in concert. The lines suppose to give the necessary firepower and the columns brought their depth and strength. But it was Napoleon who introduced this system by employing it in 1796 at the Battle of Tagliamento and during the passage over the Isonzo River. Most often the mixed order consisted of 1-2 battalions in line and 1-2 battalions in columns. Sometimes the formation was larger. Napoleon recommended to his generals that they have several battalions in lines and several in columns by division (frontage 2 companies) with half intervals. The half-intervals - in this case the length of platoon - enabled to quickly form squares against cavalry and to maneuver rapidly.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

|

|

Squares against cavalry.

According to French regulations of 1791 if the infantry was in line it sould be able to

form square in 100 sec. If they were in attack column (colonne d'attaque) 30 sec.

were enough.

Square could be also formed from column with full or half intervals. Actually to form a square was easier from a column with intervals than from line. It was expected that average trained battalion will form a hollow square in 2-3 min. In battle the infantry will need 4-6 min. To form a square from 2 battalions took approx. twice longer time. The better trained and accustomed to battle conditions infantry needed shorter time than raw troops. To form a square of equal faces took up to 2 times as long as forming an oblong.

In 1811 Marshal Davout instructed that the distances between squares should be 120 paces.

Fig. 20

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Fig. 21

.

.

.

.

Fig. 24 Generally square was a formation wherein the center was occupied only by few men (commander, color-bearer, wounded etc.) Ensign Gronow of British 1st Foot Guard writes: "Our squares presented a shocking sight. Inside we were nearly suffocated by the smoke and smell from burnt cartridges. It was impossible to move a yard without treading upon a wounded comrade, or upon the bodies of the dead; and the load groans of the wounded and dying was most appaling. At 4 o'clock our square was a perfect hospital, being full of dead, dying, and mutilated bodies." Wellington himself took refuge in this square. He appeared very "thoughtful and pale." In square's corners would be posted marksmen and pick up cavalry officers and trumpeters. Sometimes individual cannon was posted in the front corner of the square. The roaring gun made proper impact not only on the charging cavalry but also on own infantry. However if the ammunition wagon was hit and exploded it created havoc. If the square decided to move (attack or withdrew) the guns and wagons hindered its movements and could cause disorder. The presence of artillery greatly increased the chances of success against cavalry. There were however very few cases where the cavalry routed the artillery and broke the squares. In 1813 at Hanau, 8 French squares supported with 18 guns were routed by 20 squadrons of Bavarian cavalry. In 1813 at Dresden, the Saxon cuirassiers rode through the village of Alt-Franken and advanced against 2 battalions of Austrian infantry. Although the Austrians formed squares and were supported with 2 guns, the Saxons broke them and took prisoner all men and guns. (Due to rain the Austrian infantry were unable to fire many muskets.)

Solid squares.

The development of the attack column during the Revolutionary Wars introduced a solid

square (also called closed column). Differing from the hollow square,

the solid square was a dense formation, formed by having the companies closing the

intervals and having the men on the sides and the rear turn to face outwards.

'Egyptian squares.'

In Egypt, Napoleon's army faced the fierce but undisciplined Mamelukes. Although heavily

outnumbered Napoleon realised that the only enemy's troops of any worth were their cavalry so

he arranged his troops in large divisional squares with the

front and rear made up of a demi-brigade each and the third demi-brigade of the division

making up the two sides of the square. The squares had 3-rank deep walls.

Cavalry and baggage hid within these squares. The large squares repelled the Mamelukes

with artillery fire supporting.

The small, hollow or solid, squares (of battalion size) were used for the offensive.

They were formed quicker and moved faster. The were only few cases when the large and

slow squares were used offensively. It happened in 1790s in Egypt and in early 1813 in

Germany. In both cases the French cavalry was much weaker in numbers and quality than enemy's horse.

Multi-battalionn squares were also formed when the battalions were very weak. In 1813 at Leipzig, battalions of Russian II Infantry Corps were only 100-200 men each. When they formed squares they were so small that there was no place for senior officers and for the wounded inside them.

Squares in combat (part 1).

For the squares, the first attacks were usually the ones that came closest to causing panic. "The first time a body of cuirassiers approached the square into which I had ridden, the men - all young soldiers - seemed to be very alarmed. They fired high and with little effect, and in one of the angles there was just as much hesitation as made me feel exceedingly uncomfortable" - wrote an officer of British Royal Engineers at Waterloo. If the square was broken very many infantrymen were killed and wounded, many lost fingers and hands as they sought to protect themselves from sabers by holding their muskets over their heads. Others threw themselves down. Horses were unwilling to step upon prone body. The excited cavalry usually passed over their heads, they quickly rose to their feet and either run to the rear or fired at attackers' backs. This is what the Russian infantry did at Eylau, the British at Waterloo, and the Prussians at Strigau. Kincaid writes: "[at Waterloo] hundreds of the [alles] infantry threw themselves down and pretended to be dead, while the cavalry galloped over them, and then got up and ran away... I never saw such a scene in all my life.".

However, the infantry square was THE best formation against cavalry.

The square presented rows of bayonets ahead of them and no horseman

armed with saber would have been able to strike at them without exposing himself and his

horse to the sharp points of bayonets. Horses were unwilling to impale themselves on

bayonets.

There were four popular methods of cavalry attacks on the square.

Usually there were more horses killed and wounded than riders. The cavalryman instinctively

"ducked" under fire becoming smaller target. Horse is a bigger target than man anyway. A fast moving horse when hit and falling required several paces to fall down. Therefore it was unwise to fire at less than approx. 12 paces. Otherwise the square was hit by falling and kicking (if wounded) horses. One horse could make a big gap in the wall of square, bowling and wounding the men. If the volley is delivered at 12-25 paces, it will raise up a rampart of dead and wounded men and horses which will probably suffice to repulse the charge. However an infantry square rarely reserves its fire so long; and if the fire is delivered at any considerable distance, no such effect will be produced.

In many cases the infantry began to shuffle what created the neglecting of

firing. In 1815 at Waterloo, Captain Scriba was in a large square formed by two Hannoverians

battalions. He heard the pistol-armed commander of one of the squares threaten to shoot

anyone who fired before the order was given. Scriba saw the French cuirassiers under Colonel

Crabbe move forward at a trot, take a few losses caused by the massed fire from the squares,

and then, still 40-50 paces away, change direction and disappear without even trying to attack.

It was not easy to break a square even for quality cavalry. - - Chasseurs of Napoleon's Imperial Guard. - - Dragoons of Napoleon's Imperial Guard. - - several charges of Russian Lifeguard Hussars.

Approx. 1 % (10 % ?) of cavalry charges against infantry in square would be successful.

Some of the most successful cavalry charges were at Dresden, Garcia Hernandez, Hanau,

Fere Champenoise and Mockern (Leipzig.) Below few more examples.

It was a disaster for Marmont's infantry.

It was a disaster for Marmont's infantry. Jurgass sent forward 1st West Prussia Dragoons, Lithuania Dragoons and several regiments of Landwehr cavalry. Total of 2.000-3.000 of cavalry flooded French positions. The dragoons attacked French cavalry, broke them and pursued towards Gohlis. They also captured 4 guns and took prisoners. Another group of cavalry, dragoons and Landwehr, attacked battalion deployed in line and broke it by attacking one flank. Battalions of 1st and 3rd Marine Infantry formed squares and attempted to halt the Prussians. But the Mecklenburg hussars took them from the rear while from the front attacked Prussian infantry. The marines broke in the instant, lost a flag and 700 prisoners. The 2nd Leib Hussar Regiment took 2 French flags and 2 guns, and the Landwehr and national cavalry captured several guns. The 7th and 8th Brigade continued their advance behind the victorious cavalry, but there was little or no resistance from Marmont's troops.

If the cavalrymen were determined enough they would move into such gap and break into center

of the square. Only equally determined infantry might still be able to close the gap and

bayonet the bravados. It took place in 1812 at Krasne, and in 1815 at Quatre Bras.

More examples below:  General Letort, commander of the French Guard Dragoons, recognised the Fusiliers by their

Berg uniform. He thought that, since the hopelessness of their position would be obvious to them, their loyalty might waver.

He rode up and demanded they desert the Prussian army.

A shot rang out and Letort fell dead from his saddle. Fusilier Kaufmann of the 12th Company

had leapt out of the square and given the enemy general his answer, in powder and lead. The battalion continued to

withdraw but just before it reached the wood, the enemy cavalry approached again. The 10th Company faced front

while the others continued their movement. At this critical moment, the full force of the enemy cavalry charge it home."

General Letort, commander of the French Guard Dragoons, recognised the Fusiliers by their

Berg uniform. He thought that, since the hopelessness of their position would be obvious to them, their loyalty might waver.

He rode up and demanded they desert the Prussian army.

A shot rang out and Letort fell dead from his saddle. Fusilier Kaufmann of the 12th Company

had leapt out of the square and given the enemy general his answer, in powder and lead. The battalion continued to

withdraw but just before it reached the wood, the enemy cavalry approached again. The 10th Company faced front

while the others continued their movement. At this critical moment, the full force of the enemy cavalry charge it home."

Artillery vs Square. The easiest way to break the square was to bring horse artillery and blast the infantry away. In 1813 at Dennewitz, two Prussian batteries coordinated their action with III/4th Reserve Infantry "completely deployed as skirmishers" (- G. Nafziger "Napoleon's Dresden Campaign" p 266) Two Wirtembergian battalions formed in squares were broken by canister fire and suffered horrible casualties. (One square lost 531, only 70 escaped !) To bring the guns close to the square however was not as easy as it seems. Often the cavalry made continuous charges and counter-charges against the enemy's horsemen, any batteries would have been overrun as each wave of horsemen was forced, or merely retired, to reform in the rear. With no close friendly infantry to seek cover with the gunners would have been slaughtered or have to mount up and abandon their pieces in the heart of the enemy position. The only other alternative, that of continually limbering and moving downslope, then returning and unlimbering again would hardly be practical. Furthermore, coordination between artillery and cavalry was a more difficult matter and it was not frequently done. The guns needed time to arrive, unlimber, load and open fire. The situation on battlefield however changed quickly and before the guns were ready, enemy's cavalry counter-attacked. The cannons were lost and the gunners were either scattered or cut down.

Below are examples of successful coordination between cavalry and horse artillery

in breaking the square.

Line and column vs cavalry.

Examples:

Receiving the attacking cavalry while formed in column was also not the best solution.

There were however rare cases where the column or line of infantry withstood the

cavalry attack.

There were few instances where the infantry actually executed bayonet charges against

cavalry.

There were cases where the infantry has spent night in squares. For example Dedem writes how in 1812 his infantry "were making

30 to 35 miles a day, and in the evening we lay down regularly in square, having two ranks alternatingly on their feet and one sitting down."

After the battle of Shevardino some French battalions spent part of the night in squares.

In 1813 at Bautzen the French

"slept in squares by division" on the fields around Klix. It prevented Russian and Prussian cavalry to make

a surprise attack. In 1815 after the battle of Ligny some French battalions bivouacked drawn up in squares and with

one rank under arms.

One of the most confusing situations involving squares took place in 1807 at Heilsberg.

The French infantry was formed in hollow squares, with Russian prisoners inside

them and was attacked by the Russian and Prussian cavalry.

|

|

Skirmishing.

Skirmishing was not new in Europe, During the Napoleonic Wars the opposing armies would march their infantry in column formations and deploy them in a line, shoulder to shoulder in three ranks. In front of these columns and lines moved skirmishers. All infantrymen were trained in skirmishing. The skirmishers acted in 2s. The intervals between pairs were: in the French army 15 paces, in Austrian 6 paces, in Russian 5 paces. The intervals could change depending on tactical situation and available space. In 1815 at Quatre Bras the Duke of Brunswick deployed his Jager Battalion in a ditch near Gemioncourt. The jagers were in groups of 4 at intervals of six paces. They had put their large hats on the bushes in front of them. It attracted a lot of musket fire from French voltigeurs. :-)

The skirmishers used a lot of ammunition. Once the cartrdige box was empty the skirmisher went to the ammunition wagon. It would in many cases mean being withdrawn from the front line. Also the musket didn't allow for continuous firing for many hours. Russian officer Davidov noted in 1808 that many skirmishers used to spend their ammunition very quickly or throw it out in order to leave the firing line. One general said that a number of soldiers is lost to "temporary desertion" while skirmishing. But officer F.N. Glinka wrote that in 1813 after Bautzen: "...Colonel Kern wanted to relieve a chain of skirmishers, who fought for several hours. They responded: don't relieve us ! We can fight till the evening; just give us cartridges !"

The greatest danger to skirmishers came from the cavalry.

Beskrovnyi writes; "[when cavalry attack the skirmishers] The officer ... collects his

men into groups of about 10 men. They stand back to back and continue

firing and thrust their bayonets into the enemy cavalrymen, and everyone should be

confident that the battalion or the regiment will come to their aid in a short time."

French skirmishers.

Tirailleur means sharpshooter, a skirmisher in French. The French tirailleurs acted in twos and only fired one at a time so that one

was always loaded. The intervals between twos were 15 paces.

Company of infantry deployed into skirmish chain (tirailleurs de marche et de combat)

acted in concert with parent battalion for which they scouted on the march

and covered during battle. They were used to repulse the first posts of the enemy, and to

probe his position. The object was to throw back the enemy skirmishers onto his attacking

troops and - if possible - to carry disorder to its columns.

According to Marshal Davout's instructions issued in 1811, when a company was send

forward to act as tirailleurs it first marched 200 paces away from the battalion. Here the

center section halted while the left and right section of the company marched forward a

further 100 paces.

Several companies or even battalions could be employed as skirmishers (tirailleurs en grande bande).

The tiralleurs en grande bande acted in large numbers, stormed or defended a position,

or turned the flank of the enemy. The large skirmish formations were usually supported by

columns and artillery. At Friedland General Oudinot had deployed 2 full battalions as skirmishers into the Sortlack Wood.

In 1814 at La Rothiere four French battalions were formed in skirmish order by La Giberie to anticipate any attack which might develop in the

rear of the wood. The French on occasion deployed even entire divisions [!] in skirmish

formations. (Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets" 1996 p 111)

There is a myth, however, that only the French were capable of using entire battalions in skirmish order. In 1813 at Hagelberg the IV Battalion of Prussian 3rd Kurmark Landwehr deployed into skirmish formation and advanced forward together with two other battalion formed in columns screened by their own skirmishers. In the end of battle approx. 300 Prussian skirmishers pursued 2 battalions of French infantry (total 1.000 men). These skirmishers were joined by Cossacks and Russian guns and the French halted and surrendered. In 1812 at Borodino the Russians employed entire brigades of jagers as skirmishers. In 1813 at Dresden, Russian General Roth had several jager battalions of his Advance Guard in skirmish line along the Landgraben canal. At Borodino, Polish 16th Division fought in the wooded area near Utica having 2/3 of its strength fully in skirmish order. In 1813 at Leipzig, Prince Poniatowski deployed 6 Polish battalions into a thick skirmish line.) A Prussian officer described the French tirailleurs and their methods of skirmish combat (1806): "However, from a great distance, the bullets of French skirmishers already reached us; they were placed formidably in the front of us laying in the field and bushes; we were unacquainted with such tactics; the bullets appeared to come from the air. To be under such fire without seeing the enemy made a bad impression of our soldiers. Then, because of the unfamiliarity with this sort of fighting, they lost confidence in their muskets and immediately felt the superiority of the adversary. They therefore suffered, already being in a critical position, very quickly in bravery, endurance and calmness and could not wait for the time to fire themselves which soon proved to be to our disadvantage."

Other examples:

Russian skirmishers.

Russian commander Chichagov however claimed that Russian infantrymen (not specifically jagers)

had not enough wit and adroitness to fight in skirmish order. Barclay de Tolly considered

the French skirmishers superior to the Russians in agility and marksmanship and more effective

in the woods. Only after 1812 the abilities of French skirmishers significantly declined.

Jägers (light infantry) were usually the ones sent to skirmish. If there was insufficient number of jägers, the line infantry and eventhualy the grenadiers sent their own skirmishers. The troops were sent to skirmish by platoons or companies, which relieved each other in turn, or by entire battalions and regiments. For example a day before the Battle of Eylau, the Arkhangel Musketier Regiment was deployed as skirmishers to cover the withdrawal of the 4th Division. In August 1812 at Krasne, the whole 49th Jager Regiment was placed in front of the village in skirmish order.

There were however disagreements in the Russian army about the use of large number of

skirmishers. Published in 1811 "On Jager Training" recommended the use of entire jager

battalion (of 8 platoons) in skirmish order. The grenadier and strelki platoon

were kept in reserve behind both flanks of the skirmish line formed by the remaining six

jager platoons.

Barclay de Tolly was against using large number of skirmishers. In 1812 he wrote:

"in the beginning of a battle one is to push out as few skirmishers as possible, but to keep

small reserves, to refresh the men in the chain and [to keep] the rest behind formed in column.

Heavy losses cannot be attributed to skillful actions of the enemy, but to excessive numbers

of skirmishers confronted to the enemy fire."

British skirmishers.

The British well-drilled regulars were humiliated by American farmers, militia and Indians

fighting in lose order. The american experience made a profound impact and resulted in

tactical and organizational changes in the British army. But still the quality of the British skirmishers (except the 60th and 95th Regiment) was

below their French counterparts.

A Royal Scots officer wrote after Waterloo, that the French skirmishers were better trained, and on the whole much more effective in this type of fighting than the British skirmishers. (Barbero - "The Battle" p 255)

Moyle Sherer of the 34th Foot wrote on the British skirmishers: "Not a soul….was in the

village, but a wood a few hundred yards to its left, and the ravines above it, were filled

with French light infantry. I, with my company, was soon engaged in smart skirmishing

among the ravines, and lost about 11 men, killed and wounded, out of thirty-eight.

The best British skirmishers were from the 95th Rifles and KGL light battalions, all armed with rifles. The British Light Division was arguably one of the best light troops in Europe. In September 1813 the French commander in Spain, Marshal Soult, wrote to the Minister of War that British sharpshooters were killing the French officers in a fast rate: "the losses of officers are so out of proportion with the losses in soldiers".

Prussian and Austrian skirmishers.

Many Prussians and Austrians generals were not in favor of skirmishing and skirmishers.

For example von Freytag-Loringhoven wrote: "The Prussian infantry at one time took the

Frederician maxim of marching boldly upon the enemy too literally, and insisted that

skirmishing is the mark of a coward."

In 1813-1815 the Prussian skirmishers performed well.

A member of the Prussian 12th Brigade writes: "We moved up via Meusdorf and the brickworks

against Probstheida. The first thing that hit our skirmishers - of which I was one -

was an artillery crossfire. It didn't take long for us to be scattered. We reformed and

threw ourselves into a sunken road up against the loopholed garden wall of the village.

We waited until the French had fired a full volley at our main body, jumped out of the road

and rushed forward to take half the village. The surprised French fell back before us,

abandoning a battery of 10 guns in the centre of the village."

(Digby-Smith - "1813: Leipzig" p 195)

The most common way to provide skirmishers in the Prussian and Austrian army was to pull

out the men of 3rd rank of the battalion and send them forward.

The Prussian Jagers, Schutzen and fusiliers were light infantry and often fought as

skirmishers. Troopers from the 3rd rank of musketeers (line infantry) could also operate as

skirmishers or as reserve behind light infantry.

The Austrians had a long tradition of having excellent light troops.

Austria was a wooded, mountainous country with long borders. It was a perfect place for

light troops and skirmish formations. The Austrian light troops were superb during 1700-1800

and only before Napoleonic Wars their quality decreased.

In 1813 at Dresden the Austrians used their skirmishers in an interesting way; the

Erzherzog Rainier Regiment sent skirmishers forward and between flankers (horse skirmishers)

drawn from a hussar regiment.

Rifles.

The English Baker rifle was probably the most accurate of all firearms during the Napoleonic Wars. On the training ground and under perfect conditions 100 % hits were recorded at 100 paces. However some of the claims about superiority and universality of rifles make little sense. If they were so superior then why the musket, not the rifle, remained the weapon of British infantry for decades after Napoleonic wars.

The weaknesses of rifles were:

|

Sources and Links.

Barbero - "The Battle"

Beskrovniy, "Materials of Russian Military History", Military Publishing House of The Armed Forces of the USSR, Moscow, 1947. Chapter 11. The War of Year 1812. The Manual For Infantry Officers In the Day Of Battle. (quoting from "The Centenary of the War Ministry", S.Petersburg, 1903. Volume 4)

Nosworthy - "With Musket, Cannon and Sword..."

Rothenberg - "The Napoleonic Wars (History of Warfare)"

Elting - "Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grand Armee"

Zhmodikov - "Tactics of the Russian Army in the Napoleonic Wars" Vol. II

Chlapowski - "Memoirs of a Polish Lancer"

Nafziger - "Imperial Bayonets...". 1996

Bowden - "Napoleon's Grandee Armee of 1813"

Nosworthy - "The Anatomy of Victory"

Arnold - "Napoleon Conquers Austria"

Chandler - "The Campaigns of Napoleon"

Muir - "Tactics and the Experience of Battle in the Age of Napoleon"

Chlapowski - "Mamoirs of a Polish Lancer" (translated by Tim Simmons)

Esposito, Elting - "A Military History..."

"A Reappraisal of Column Versus Line in the Peninsular War - Oman and Historiography"

link

Plates: règlement concernant l'exercice

et les manoeuvres de l'infanterie du 1er août 1791

(Imprimé à Metz : 1793)

Infantry Tactics.

Civil War (USA) Infantry Tactics.

Roman Infantry Tactics.

German Infantry Tactics.